Christopher Capozziello’s “The Distance Between Us” is a poignant examination of the life of Capozziello’s fraternal twin brother, Nick, who has cerebral palsy.

Capozziello has been photographing Nick for 13 years and has a Kickstarter campaign (through Sunday) to help fund the publication of his book of the same title in November by Edition Lammerhuber. In the book, Capozziello addresses the shame and guilt he’s felt at being able to lead a “normal” life, free of the suffering his brother has endured. “There are moments I struggle with photographing and including in the book, and sharing in general,” Capozziello wrote via email. “Eventually, I came to a place where it was obvious that I needed to tell this story.”

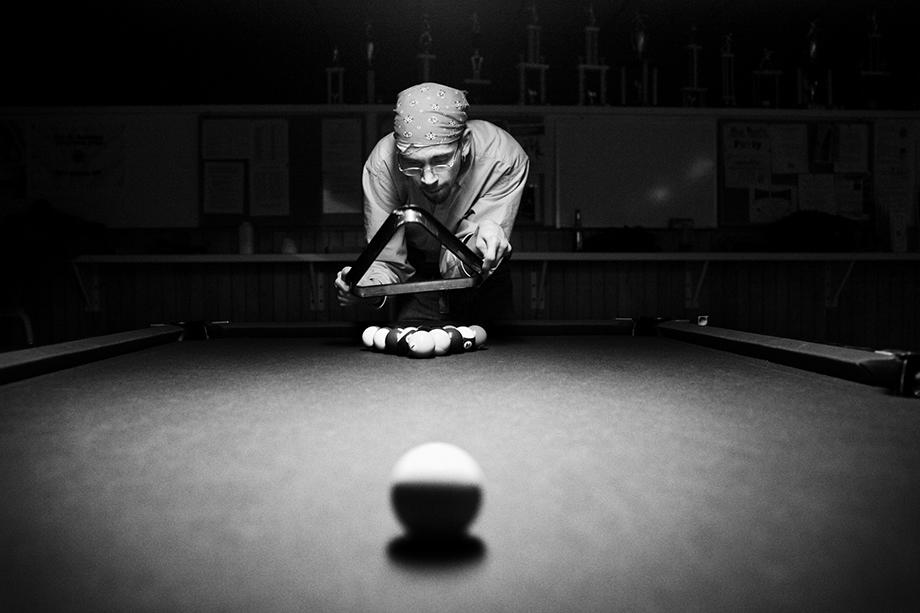

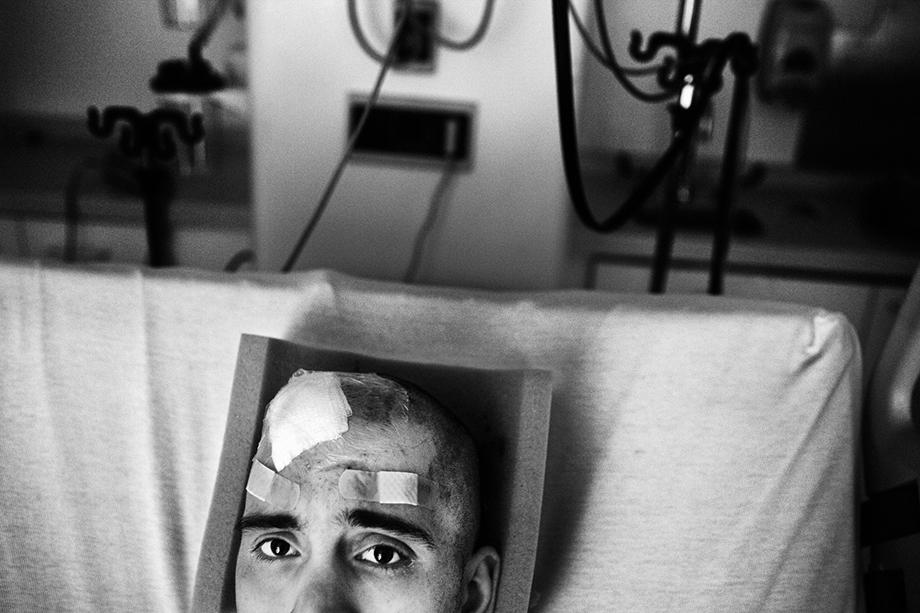

Photographing Nick during periods of happiness—hanging out at a local bar or shooting hoops—was easy, but telling parts of Nick’s story, including a painful surgery and recovery to try to alleviate cramps, were more complicated and forced Capozziello to question his ideas of both photography and the project. “It seemed wrong to make so many pictures of him hurting, and many times, I wanted to put the camera down and look away,” Capozziello said. “Those are the images I have the hardest time sharing—pictures where he’s all twisted up, unable to communicate or move on his own—pictures where he looks so defenseless and vulnerable. I share those images because it’s part of his experience, but it’s not at all comfortable.”

Christopher Capozziello

Christopher Capozziello

Christopher Capozziello

Capozziello said making personal photographs public brought up emotions he had never shared with his family. “Often times, it’s assumed that the pictures I’ve made of Nick have been a cathartic experience. At first they were not,” he said. “I was afraid of what that honesty might mean to my family. I had never shared with any of them my feelings of guilt in this way and in those words [that appear in the book]. There’s a lot that often isn’t discussed with those that are closest to us. In some ways, I was shielding them from my sadness, and anger.”

Working as a war photographer has always been a dream of Capozziello’s, but he avoided it because he felt that his family would be devastated if something had happened to him. It’s part of a push-pull relationship he has with his family and Nick and one that he describes in the project. “As I enter new seasons in my life—leaving for college, and starting a career—our differences become more pronounced, and I often feel like I’m leaving Nick behind, as if he’s stuck in time,” Capozziello said. “If I ever get married and start a family, I know I’ll deal with guilt in some way because Nick wants those things, too. He understands the world enough to know what he’s missing out on, and I think that will always be something that is hard for me to deal with.”

Christopher Capozziello

Christopher Capozziello

Christopher Capozziello

Although his parents look past Nick’s disability to see his humanity more fully, Capozziello said he’s struggled to see beyond his and Nick’s differences. “I think that’s because we’re twins, and standing next to him, I’m the constant reminder of what life could have been like for him,” Capozziello said. “It’s created a burden, one that I think I felt for a long time was fair to carry for him. In some ways, I felt it was just.”

Capozziello hopes that people will both look at the photographs and read the text in order to understand the relationship between him and his twin. “I think that suffering itself connects people in ways that other aspects of life cannot,” he said. “Through the text, Nick has come to know that he is not the only one that suffers from cerebral palsy, that we all suffer alongside him, but there is beauty even in the pain. I hope people make that connection and that people see him, and others who live with a disability, as more than their affliction.”

Christopher Capozziello

Christopher Capozziello

Christopher Capozziello