Think of a bird’s nest and you might picture a simple, neat cup of sticks and grass nestled on a tree branch.

But as Sharon Beals found out in photographing her book, Nests, birds may be “nature’s most fastidious architects” that create these structures in all shapes and sizes using a variety of materials.

“There are those that build with mud, burrow tunnels, weave hanging pendulous baskets or cups onto branches, stitch leaves, stack sticks, or glue with saliva. Some just make simple scrapes on the ground, or fill cavities with fur and bones, and others that camouflage their nests with lichen, spiderweb, or moss,” Beals wrote in her book.

Beals grew up enjoying nature in the Seattle suburbs but didn’t pick up a pair of binoculars until decades later. Her passion for birds truly began after reading Living on the Wind, Scott Weidensaul’s study of aviation migration.

Spotted nightingale-thrush (Catharus dryas harrisoni). Collected from Cerro Baul, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1968. Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology.

With large eyes ringed in orange, yellow-spotted chests, and orange legs and feet, spotted nightingale-thrushes are a striking member of the genus of Catharus thrushes. In spite of these markings, they can be extremely hard to find, staying hidden in the understory of the forests of the Central American highlands and the Andes, where they feed terrestrially and nest year-round. The female builds the nest using moss, lichen, and leaves, binding them with rootlets and grasses to form a deep, thick-walled cup, often woven onto a supporting vertical branch, with trailing foliage to disguise its shape.

Sharon Beals

Sharon Beals

Akekee (Loxops caeruleirostris). Collected from Kokee State Park, Kauai, Hawaii, 1970. Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology.

This cup of moss and lichen was built by a pair of Akekee in the crown of an Ohi’a Lehua tree. The last 4,000 of these small finches are found in the high rainforests of Kauai. Living above 1,800 feet, these survivors have escaped the mosquito-borne avian pox and malaria that have decimated so many other Hawaiian birds since the 1800s, when European trading ships emptied their bilges on the island. Grazing and feral animals have also destroyed their habitats. Of 113 endemic species, 71 have been lost. Of the 42 left, Akekee are one of the 32 listed as endangered.

Sharon Beals

For her book, Beals photographed nests in the collections at the California Academy of Sciences, the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley, and the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology. Scientists there value the nests for the information they contain, including evidence of environmental toxins and DNA samples.

At the California Academy of Sciences, the collection is composed almost entirely of donations from private collections composed prior to 1950, a time when nest and egg collecting was widespread among amateurs poking around their own farms or backyards. “At that time, eggs were collected in huge numbers, largely without any knowledge or thought about the impacts this might have on the local bird population. At least a couple bird species were driven to near extinction by egg and nest collecting,” wrote Jack Dumbacher and Maureen Flannery in the book’s forward.

Nest-collecting was banned in the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, but the samples remain in scientific institutions across the country. Nests are now collected extremely sparingly for scientific research purposes, but Beals still had thousands of nests dating back hundreds of years from which to choose. “I was looking for a few nests of birds which were facing some conservation challenges. I tried to photograph nests from across the taxonomic order, the widest range I could, so when I was doing the book it wouldn’t be all sparrows. Then I tried to find nests that were collected in different countries so it wouldn’t look so U.S.-centric,” she said.

Beals photographed about 100 nests using a rented high-definition camera. For Beals, who has worked as a commercial photographer for many years, the technical aspects of the shoots were simple. She did find a challenge in learning the taxonomic order so she could find the corresponding eggs, stored separately from the nests.

In all, Beals said the process opened her eyes to the range of designs and materials in nest-building.

Golden-winged warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera). Collected from Sterling State Forest, Orange County, New York, 2001. Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates.

These neotropical migrants breed in the shrub lands, disturbed forests, and abandoned farmlands of eastern North America. Females lay a foundation of leaves and weave a loose inner cup of vines, strips of bark, or other plant materials. Densely replanted reforestation, fire suppression, the loss of farmlands, and incursion into their territories by blue-winged warblers, with whom they hybridize, are all factors contributing to their threatened status.

Sharon Beals

Hoary redpoll (Acanthis hornemanni). Collected from St. Michael, Nome County, Alaska, 1896. Museum of Vertebrate Zoology.

These tiny seedeaters survive minus-80 degrees Fahrenheit Arctic temperatures by doubling their weight in down in winter and living off plants not buried under the snow. Using a pouch in their esophagus, they can store seeds to be regurgitated and eaten under shelter. They also build well-insulated nests lined with willow cotton, caribou hair, vole fur, feathers, fine grass, and in this case, even sheep’s wool.

Sharon Beals

Cuban emerald (Chlorostilbon ricordii). Collected from Andros Island, Bahamas, West Indies, 1988. Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology.

These winged jewels are common in Cuba and the Bahamas, with a few found in Florida. Like all hummingbirds, nest-building and care of the young is the responsibility of the female. They attach their nests to supporting forks of a branch in a shrub or vine, frequently in a young coffee plant. Their well-hidden 2-inch cups are made of silky plant fibers and moss bound with spider web, with long trailing grasses and strips of plant bark that disguise its shape, and bits of lichen and bark attached to its exterior.

Sharon Beals

Although Beals appreciates the beauty of the nests and remains in awe of their construction, she’s not out to romanticize them. Doing the research for her book made her acutely aware of the challenges facing wild birds, and she has become an advocate of their birds’ protection. “Life is hard for birds. … While many have adapted to, and even benefited from, human machinations of their habitat, if it is polluted, overrun by feral animals or introduced insects, or just [destroyed], a whole species can be lost,” Beals wrote.

With native habitats for birds shrinking every year, Beals said she finds it increasingly urgent to raise awareness and encourage action. In order to provide a better habitat for birds in her own neighborhood, Beals has bought native plants for her garden, and she suggests others make similar adjustments to their own environments to make them more accommodating for birds. “I’m trying to be respectful of everyone’s interests and whether or not they want to know, but sometimes I feel like I have to tell this story,” she said.

In that same spirit, Beals is looking to make another book chronicling the nests of 590 birds that are categorized as endangered, critically endangered, near threatened, or extinct in the wild.

You can see some of Beals’ photos on display at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., through May 2014.

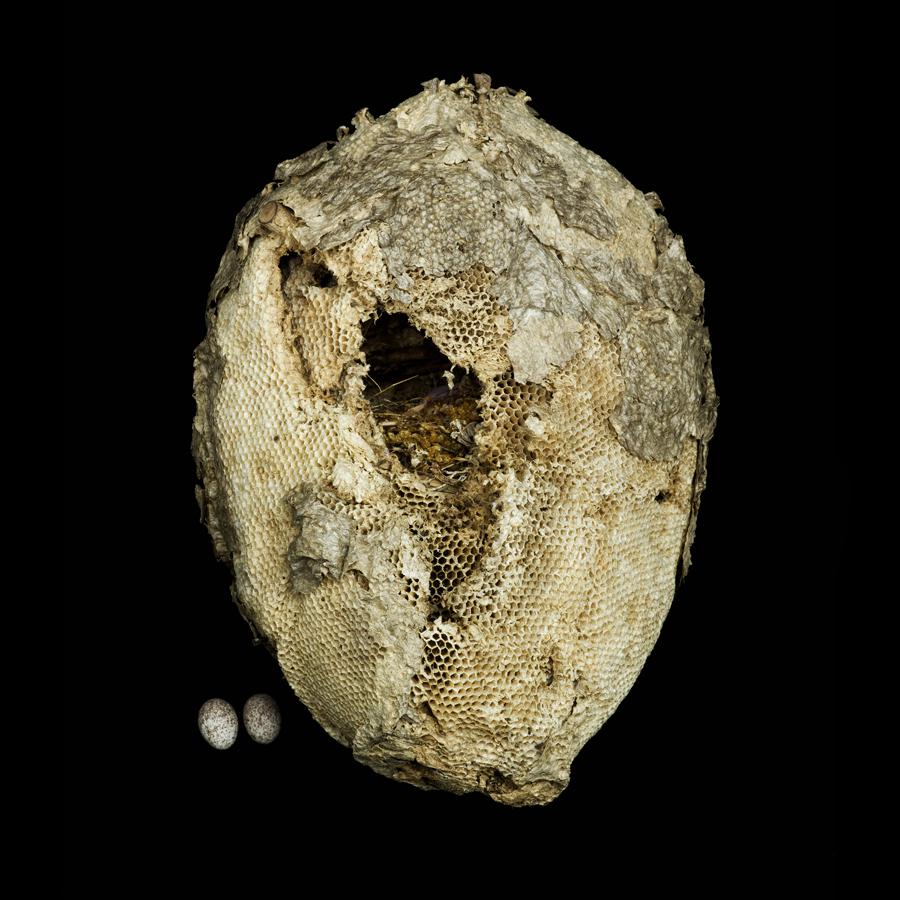

Altamira oriole (Icterus gularis). Collected from Morazón, El Progreso, Guatemala, 2001. Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology.

Relatives of blackbirds and meadowlarks, altamira orioles can be found from the Rio Grande to Nicaragua, living in year-round territories as lifelong pairs. It can take the female a month to weave a pendulous nest, which is entered from the top, with a nesting chamber at the bottom. In Texas, altamira orioles are considered a threatened species due to the loss of the native trees of the Rio Grande to agriculture and flood control.

Sharon Beals

Tree swallow (Tachycineta bicolor). Collected from Tatoosh Island, Callam County, Washington, 1995. Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates.

These iridescent aerialists nest in cavities of older trees and snags, often those created by woodpeckers. Goose feathers insulate this loose cup of grass and twigs found in one of these natural nesting sites, which have been disappearing over the past 200 years. They will readily occupy nest boxes as substitutes if they are placed near sources of insects, the mainstay of their diet.

Sharon Beals

Verdin (Auriparus flaviceps). Collected from Sierra La Mojina, Chihuahua, Mexico, 1961. Museum of Vertebrate Zoology.

The only North American member of the penduline tit family (Remizidae), these tiny insectivores survive bitter winters and searing summers in the arid forests, scrub lands, and deserts of the American Southwest and Mexico. They manage this year-round residency by building small thorny domes for both breeding and roosting. Fledglings as young as 3 months construct their own nests, and in a year a verdin may build a dozen solo shelters.

Sharon Beals