World War II transformed New York City.

A new exhibit presented by the New-York Historical Society, “WWII & NYC: Photography and Propaganda,” tells that story. Drawn from a vast collection of historical images, including many from U.S. Navy archives, the exhibit shows how the war touched every aspect of life.

“It attempts to create a better sense of what ‘total war’ meant to New Yorkers, whether they were working at the Navy Yards or just going about their daily lives,” said the historical society’s Chelsea Frosini.

Among the most dramatic changes to the city during wartime was an explosion of production and movement. According to the society, 63 million tons of supplies and more than 3 million men shipped out from New York Harbor, and at the height of the war, a ship left every 15 minutes. The Brooklyn Navy Yard doubled its size and employed 70,000 people, including many women; it became the largest shipbuilding facility in the country at the time.

“It had the shipping and railroad infrastructure to really be the Army and Navy’s warehouse for sending troops, ships, planes, guns, bombs, toilet paper, thumb tacks—whatever they needed—to Europe,” said Mike Thornton, a research associate at the New-York Historical Society. “We sent it all. The port has never been that busy since.”

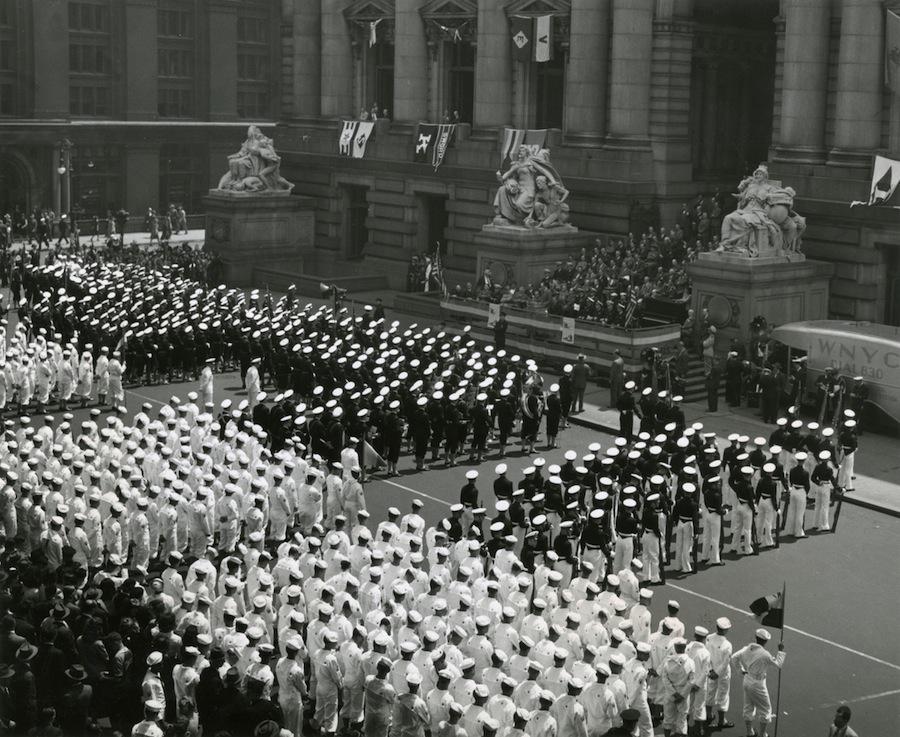

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

The war also changed the look of the city. Times Square, Broadway, and other iconic locations shut their lights in observance of a “dim-out” meant to protect the city from attack. Posters inundated public spaces to promote the war effort and instruct civilians how to respond to an air raid or naval strike. And the streets saw occasional floods of soldiers on Liberty Leave, there to enjoy the city for 24 hours of freedom.

City institutions, including museums and universities, took on new functions to contribute to the war effort. Between 1943 and 1945, the Bronx campus of Hunter College (now Lehman College) accommodated more than 80,000 female Navy reservists, called the WAVES, for boot-camp training. People in the armor department at the Metropolitan Museum started producing equipment for the war. Even the New-York Historical Society was transformed into an American Red Cross bandage-rolling station.

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

The war also impacted individuals. Families grew victory gardens and had ration cards to get groceries and fuel. Children participated in air raid drills and created models of enemy airplanes for the Civilian Defense Corps to use as reference. And with 900,000 New Yorkers serving in the military, many people in the city had friends and family fighting overseas.

“You couldn’t have missed the war,” said Thornton. “It really required a total civilian contribution.”

The exhibit, which was curated with help from high-school-aged student historians, will be on view on Governors Island through Sept. 2.

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Official U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

Update, March 10, 2014: The seventh photo’s caption has been updated to reflect that Grant’s tomb is not pictured in the image; it is located just outside the image’s parameters. Riverside Church is behind the seamen.