When you literally watch a beloved industry get blown up, it can be life-altering. The photographer Robert Burley can attest to that. In 2005, Burley, who lives in Toronto, began visiting and photographing the Kodak Canada complex in the Canadian city after learning about plans to shut down the plant.

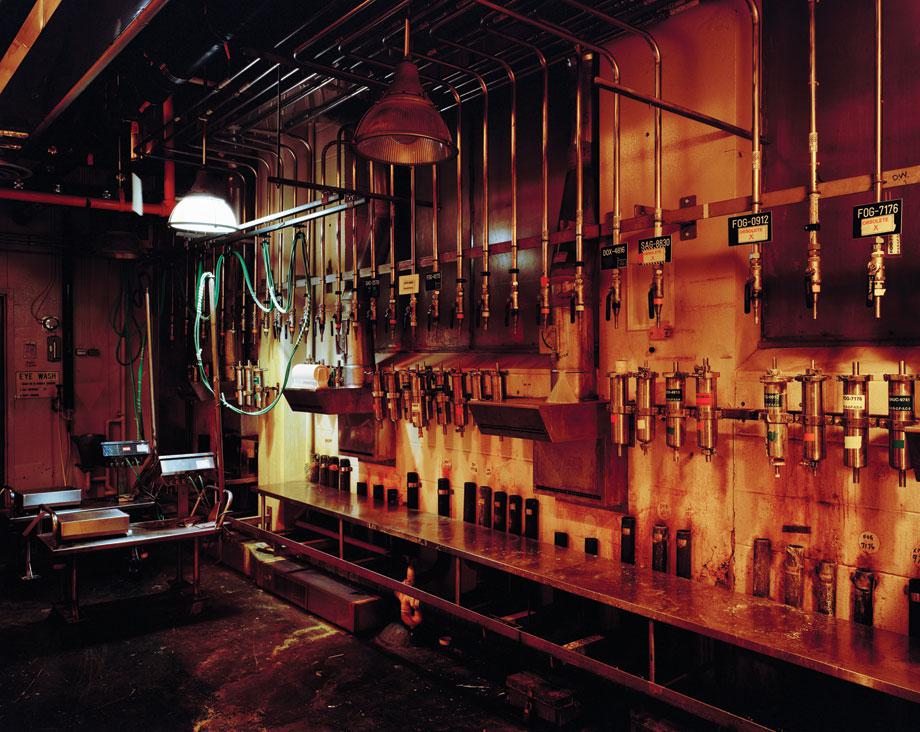

He spent a year and a half documenting the 18 buildings on the campus, where he was given full access. During that period, he learned a lot about the previously secretive processes about how film was manufactured and was surprised about how little he knew about the medium he had loved since he was a teenager.

And then in 2007, Kodak began blowing up their buildings in Rochester, N.Y., one of many closures and implosions of film producing factories around the world he would document.

“To read newspaper stories about the decline of traditional film was one thing but to stand in front of one of those film factories and watch it reduced to dust in a matter of seconds was quite another,” Burley wrote via email. “In retrospect, attending these scheduled implosions of the Kodak factories was the most poignant part of this 6-year project. These occasions were sad, sublime and ironic all at once. I included the crowds in my photographs noting most everyone was documenting these spectacles with a digital capture device … of some kind—even though most had been employed by Kodak and worked in these buildings for the better part of their lives.”

![Left: AWAItInG the IMPlosIons oF bUIldInGs 65 And 69, KodAK PARK, RoChesteR, neW yoRK OCTOBER 6, 2007. Right: IMPlosIons oF bUIldInGs 65 And 69, KodAK PARK, RoChesteR, neW yoRK [#1] OCTOBER 6, 2007](https://compote.slate.com/images/32344aff-93cc-46c6-a7de-f5a9de430370.jpg?crop=920%2C357%2Cx0%2Cy0)

Robert Burley

Robert Burley

Robert Burley

Robert Burley

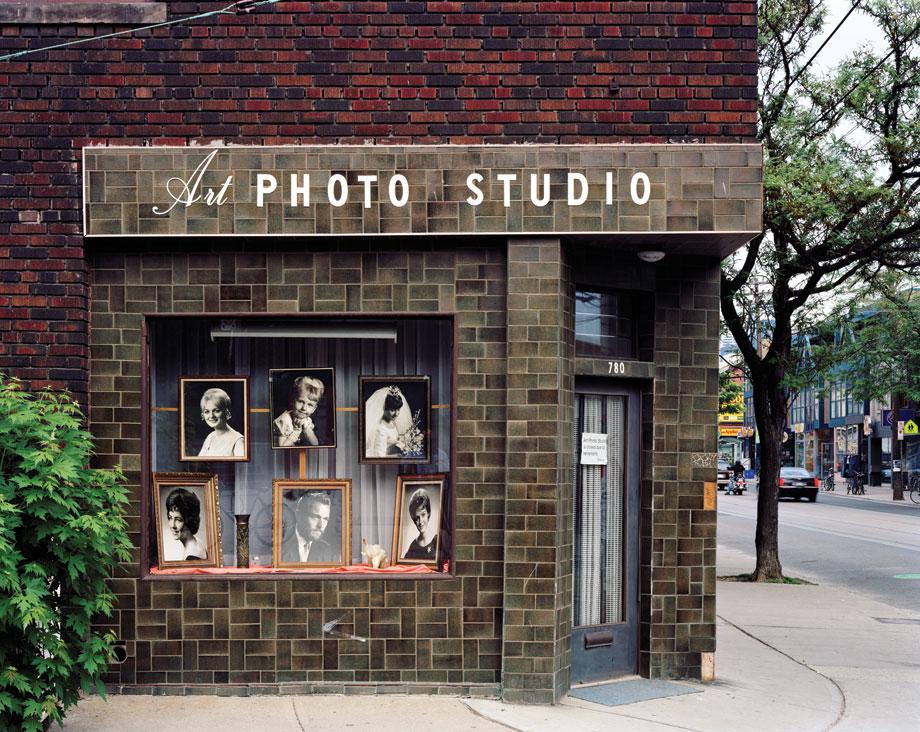

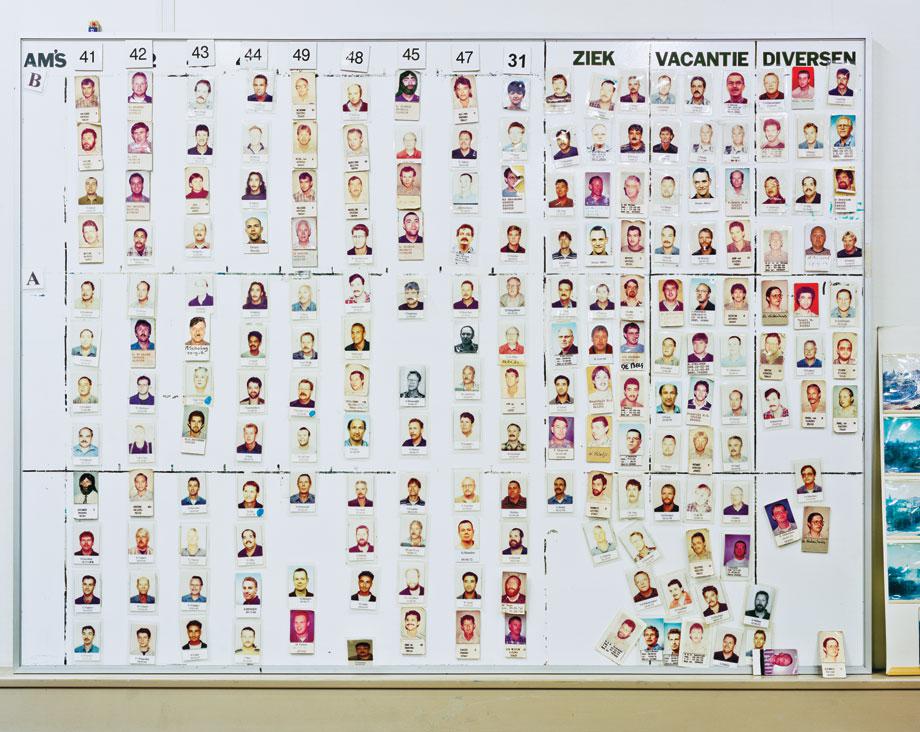

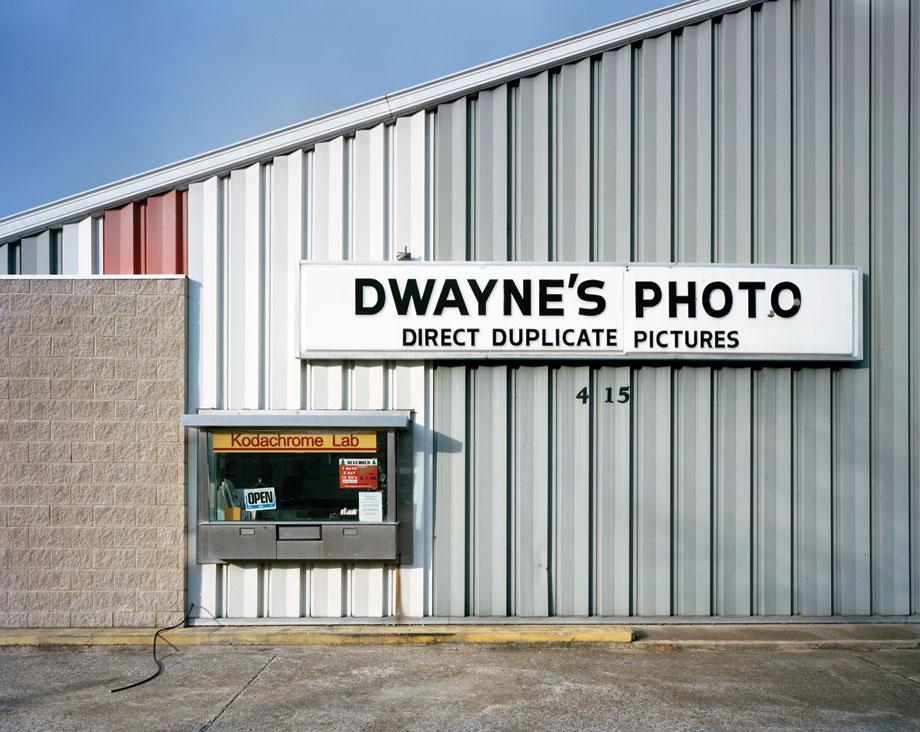

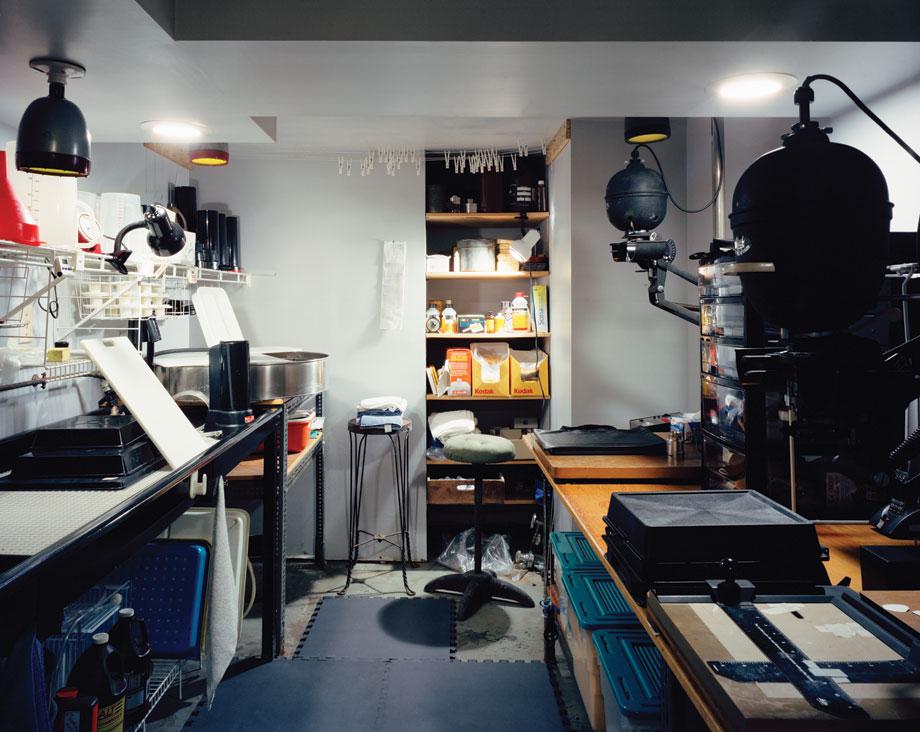

The result of the six years Burley spent documenting the demise of the film industry became a book, Disappearance of Darkness: Photography at the End of the Analog Era, published by Princeton Architectural Press. The book profiles not only the demise of the factories but it is also a nostalgic look at some of the ways film photography is embedded into our collective memories including images of photo booths and studios, darkrooms and even a shot of Dwayne’s, the last lab to process Kodak’s iconic Kodachrome film.

Burley doesn’t see the conversation between digital and analog photography as an either/or debate, although he said while working on the book, it became clear “that photography was not simply undergoing another technological shift or refinement—it was being irrevocably changed forever.”

Instead, Burley compares the two formats to the way people used to compare horses and cars, noting that the car shaped not only the way people traveled but also the design of cities. “Digital media are changing the way we see and experience the world around us—even the way we see ourselves in the world,” he said.

Robert Burley

Robert Burley

Unfortunately, that doesn’t translate to revenue for film manufacturers that have seen their market dwindle as amateur photographers have embraced digital photography. “As I visited the gutted Polaroid factories in Boston, the Agfa and Ilford plants in Europe and many other buildings related to photography’s everyday uses in the world it became clear that photography as I had known it was quickly passing into history,” Burley said. “An alarming number of films have disappeared over the last two decades and I believe this trend will continue with the elimination of color film in the near future. My hope is that [black and white] materials will be available for a long time—the Ilford company appears to be in good position to continue this role.”

Burley chose to photograph the images in the book with film but said it wasn’t a sentimental choice. When he began shooting the images that would become the book in 2005, Kodak was still a thriving company, and he felt film was at that point still superior to digital photography.

“By the time I finished the project in 2012 all of these things had changed—really, the whole world had changed in too many ways to count,” he wrote, adding that in February 2012, Kodak declared bankruptcy. “Suddenly, it became clear that the culture of photography as we’d all known it during our lifetime was gone—it felt as though it had suddenly become a part of a distant past in the blink of an eye.”

In addition to the book, two museum exhibitions will feature the work: the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône, France, beginning Oct. 12 and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa beginning Oct. 18.

Robert Burley

Robert Burley

Robert Burley

Robert Burley