One of the voids left behind in the digital age of photography is the excitement and mystery of picking up developed prints from a roll of film.

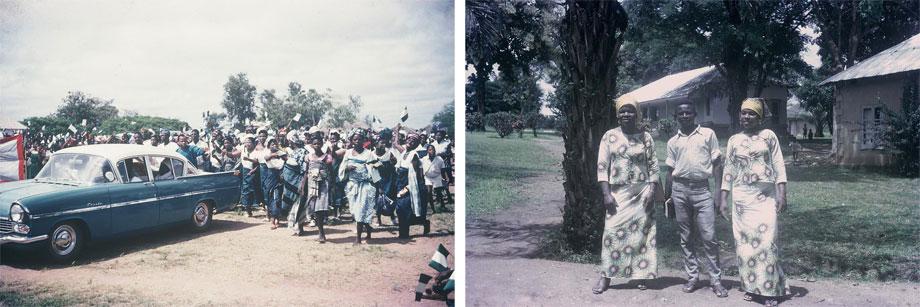

Imagine the thrill Senongo Akpem felt when he and his family discovered a trove of slide film taken by their mother, Emily, during her work as a missionary and nurse in Nigeria during the 1960s and ’70s.

“I had no idea most of this stuff was there,” Akpem said about the images. “We knew this stuff was around, but I had no idea of the depth of it.”

A family friend in Nigeria collected the film and had it developed in the United States. Since then, Akpem has started to edit the film, scanning images and uploading them to a website he started called Lost Nigeria.

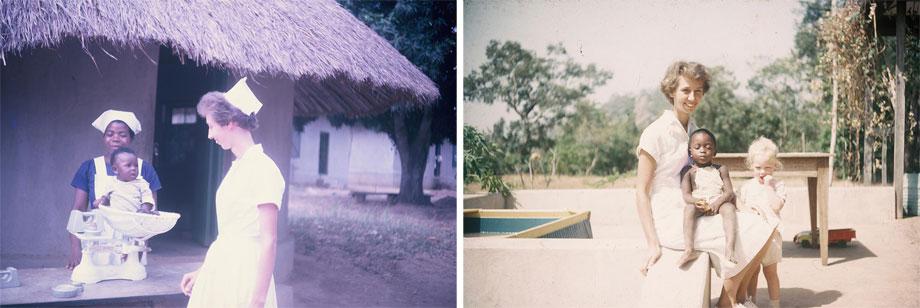

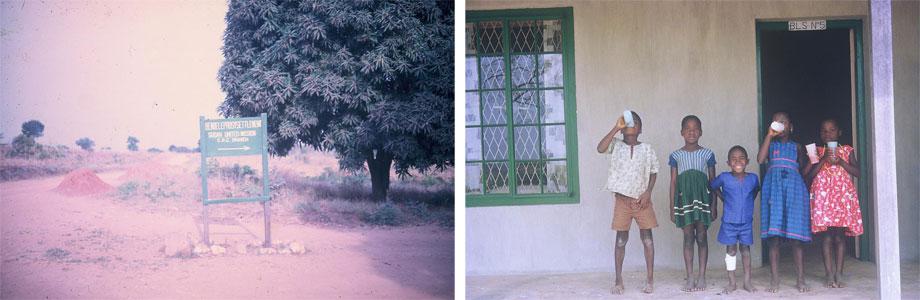

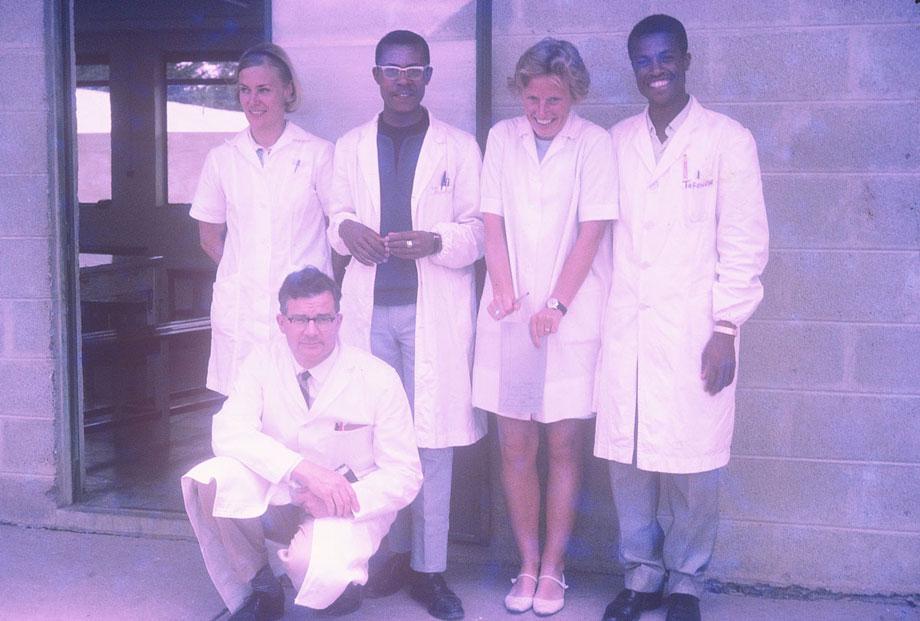

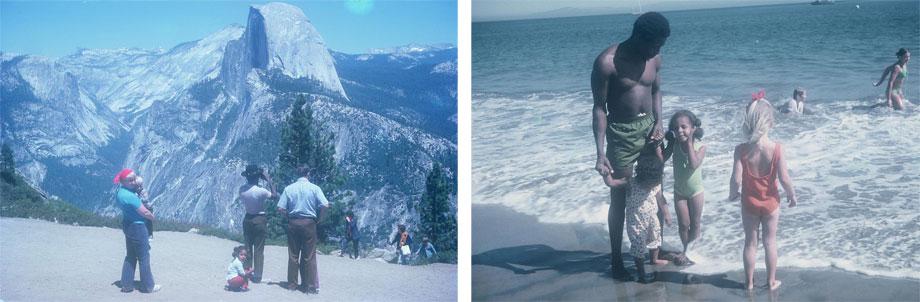

The images tell the story of his mother’s journey to Nigeria in the early 1960s, when she left her home in California to work as a missionary nurse at the Benue Leprosy Settlement. While there, she fell in love with a Nigerian reverend doctor and had three children—two daughters and a son, Senongo, the youngest born in 1979. The family moved back to the United States soon thereafter and lived between Michigan, California and Nigeria over the next decade.

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

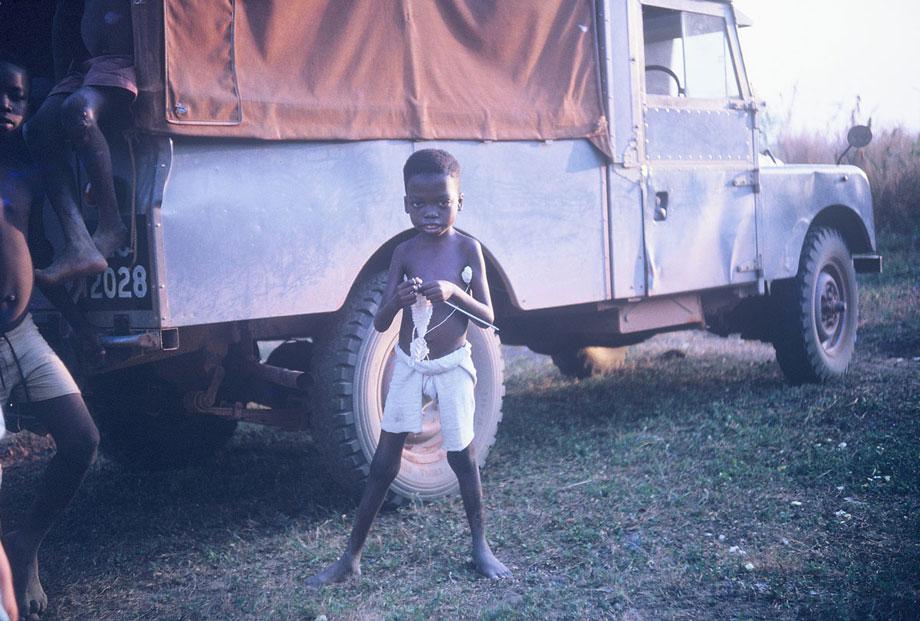

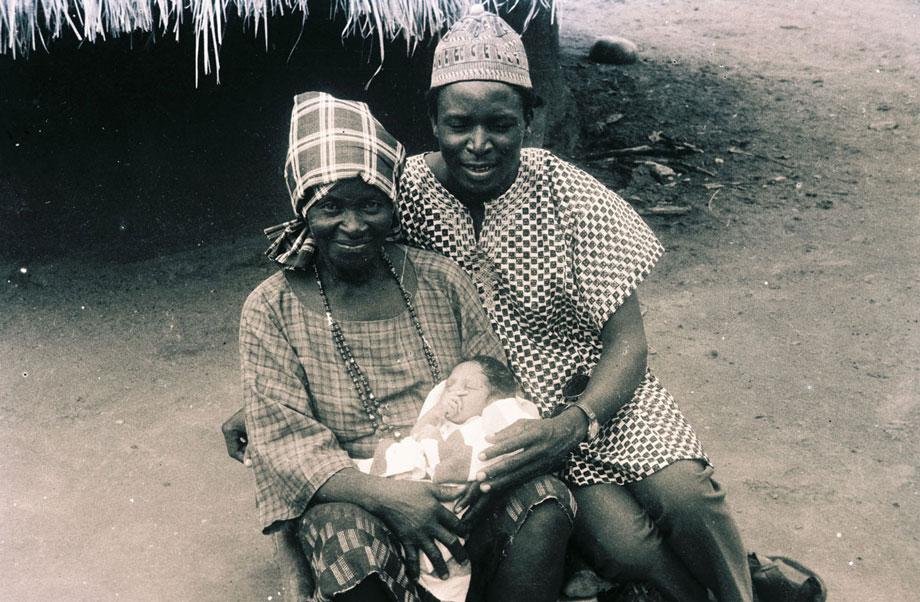

Many of the images document Emily’s early years in Nigeria, “when she was very much in love with Nigeria and Africa and my dad and with the idea of documenting her experience,” Akpem said.

Initially, Akpem wanted to edit the images in chronological order, but because few dates were given, he decided to group them thematically. The site has a personal, cultural, and historical feel to it.

“For a white woman, an American, it must have been very new,” Akpem said of his mother’s initial experience in Nigeria. “She was born a few years before World War II ended, and the way California was in those days, I would assume there were no black people where she was from, so for her to pick up everything and go to Africa, I think she found it amazing to document.”

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

Although Akpem said he sees and remembers his mother (she passed away in 2000) differently from many of the snapshots, they have also opened up a new window into her life.

“I can see through her eyes what it’s like to live in a new country and experience Africa as a non-African,” he said.

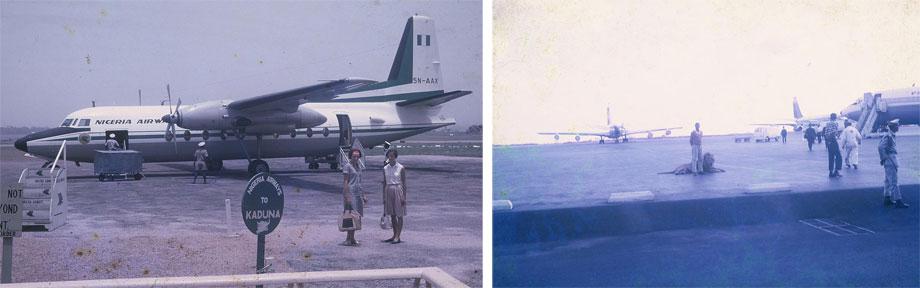

The images cover a period of 20 years from 1960 to 1980 and focus on personal, political, social, and cultural moments in both Nigeria and the United States, from Emily’s work at The Benue Leprosy Settlement to 1970s life in California to imagery of air travel and signage in Nigeria.

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

Courtesy of Senongo Akpem

“Lost Nigeria” is also a melding of old technology with modern social networking. Many of Akpem’s relatives have been happy to share the images included on the website, but there has been another, surprising element to the project.

“I still get emails from biracial Nigerians who were raised around the same time and they want to reach out and say ‘thank you’ for posting this because ‘your family’s experience was also my family’s experience,’ ” Akpem said. “People are sending me their pictures almost because they have to share this with me. I might take a few and get in touch with people and see if I can put them up on the site as a way of sharing experiences.”