Edmund Clark’s series about Guantanamo Bay isn’t simply a glimpse into one of the world’s most controversial detention camps. Clark spent three years working on what would become a book, Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out, which focuses on the naval base and prison camp at Guantanamo Bay as well as a look into the homes of released detainees.

The book presents all three environments without a direct narrative, thereby creating a sense of disorientation and inviting the viewer to create his own interpretation of the images.

“The purpose [of the camp] was to disorient, to make them [the detainees] paranoid, so I decided to use a chopped, mixed, disjointed narrative to evoke in the viewer a sense of disorientation: They’re looking at a domestic civil life, then suddenly a McDonald’s, then a church, then a force-feeding chair,” said Clark about the series. “It’s a way for people to engage with imagery so they will think more about the process of disorientation.”

Before working on the series, Clark had previously focused on projects that dealt with incarceration including a project about teenage fathers in prison and another on the problems associated with aging prisoners. He was also influenced by 16th-century Dutch painters, specifically the way they painted “ordinary objects imbued with significance about the passage of time and the ephemeral nature of human existence.” Clark found himself interested more in the spaces the prisoners inhabited rather than simply taking another portrait of an inmate.

Edmund Clark (2)

Edmund Clark (2)

Edmund Clark (2)

“I wasn’t interested in what crime they committed,” Clark said about some of his previous work. “What was more interesting were the spaces around them and what that said about the nature of long-term incarceration and its relationship to time and space.”

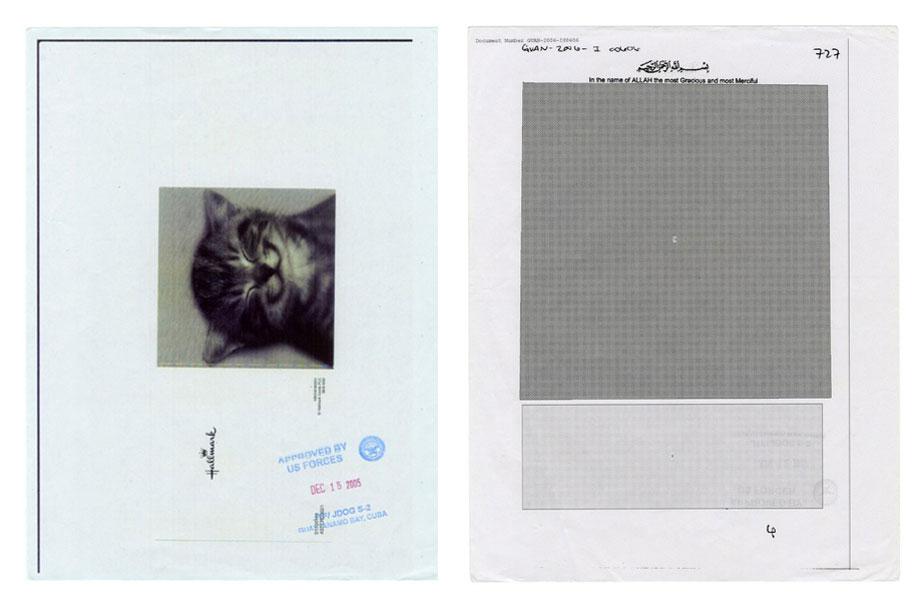

Through connections and the backing of a magazine, Clark was able to shoot for nine days at Guantanamo Bay at both the naval base and prison camp. Although shooting at the naval base was somewhat relaxed, shooting at the prison camp was another matter. The list of images Clark wasn’t allowed to take included security cameras, people’s faces, empty watchtowers, and no images with both the sky and sea visible (related to orientation). He also had to sit down with a security camera to review everything he had taken each day—using digital photography only was mandatory.

Clark didn’t want to create the kind of images he had already seen of Guantanamo—“shackled ankles, hands at windows, out-of-focus detainees”—and instead tried to define what it meant to be a detainee through the use of objects and space.

Edmund Clark (2)

Edmund Clark (2)

Edmund Clark

Edmund Clark (2)

“Clearly I’m interested in the politics of incarceration, why we do it, how we do it, the forms in which it takes, the process … you have a prison camp with issues of legality and human rights.”

“We were told these were the worst of the worst,” Clark said about the detainees. “The imagery spoke of dehumanization—we can’t even consider them to be humans … yet people were being released as innocent back to Britain. … I was interested in exploring the nuances of that juxtaposition between the representation we associated with Guantanamo.”

To do that, Clark needed to also focus on the living spaces inhabited by the detainees once they returned home. He felt that if he took portraits of British citizens with Arab backgrounds, it would simply reinforce the stereotypes viewers already had about what an Arab looks like.

“So I wanted to photograph the normality of where they live … we all have places where we sleep, eat, wash, and I hope by showing those spaces it short circuits the connection]. … I wanted to rehumanize them by a shared experience with those spaces.”

“Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out” is on view until May 4 at Gage Gallery, 18 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago.

Clark’s newest project, Control Order House, examines a man suspected of being involved with terrorist-related activity and placed under a “Control Order” in the United Kingdom. Clark explores the project through photographs, redacted documents, architectural renderings of the house, and the man’s diary.