The stables where sumo wrestlers practice their sport in Japan are places where tradition reigns and only glimpses of the modern world creep in.

“You have to see the stables more like a monastery than a gym,” said photographer Paolo Patrizi.

Patrizi, who has lived in Japan for the past eight years, was granted access to three different stables for about a month when he became interested in the sport five years ago. His series, “Gentle Giants,” shows the sumos at work and during their downtime.

“I wanted to cover as much as I could of how they live. They spend most of their lives there. They don’t go out much,” Patrizi said.

Paolo Patrizi

Paolo Patrizi

Paolo Patrizi

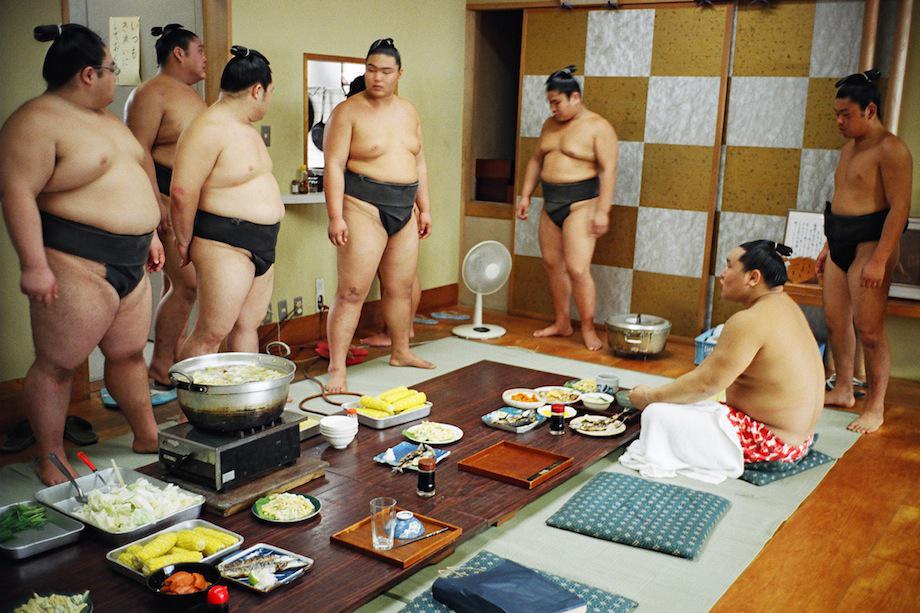

The wrestlers live, eat, and practice together at the stables. Exercises start around 6 a.m. with the juniors. A wrestler challenges an opponent, and he stays in the ring until someone beats him. At 8 a.m., Patrizi said, the more senior wrestlers come in and things get interesting.

“Some of the tough guys pick on the younger ones, and they trash them. There’s some serious beating going on. There’s a lot of bullying going on, but these guys keep quiet. They can’t complain,” he said.

Training is grueling. When the sumos do go out, Patrizi said, it’s most often on a Sunday, their day off. He says they sometimes rent videos or play video games.

Paolo Patrizi

Paolo Patrizi

Paolo Patrizi

Though they live in a modern world, the life of a sumo is generally guided by centuries-old practices, including wearing their hair in a chonmage (which is styled after a bath and a shower by a hairdresser who works specifically for the stable).

But the sport has changed.

In recent years, it’s been wracked by scandal and corruption, including drug use, gambling, and connections to organized crime.

Perhaps as a result, the number of Japanese men applying to become wrestlers hit an all-time low in 2012, and spectatorship at events has declined. Meanwhile, wrestlers from Mongolia and Hawaii have started taking championship titles away from those in Japan, where the sport originated.

“It still is a national sport,” Patrizi said. “The problem is when they do the tournaments, the top guys start fighting at 4 in the afternoon. There aren’t that many people who are able to turn on the TV to watch it, aside from the weekend, which is the final. I don’t hear many young people talking about sumo.”

Patrizi has since moved on to other projects, including a series chronicling migrant sex workers in Italy, for which he was awarded second prize in the World Press Photo Contest.