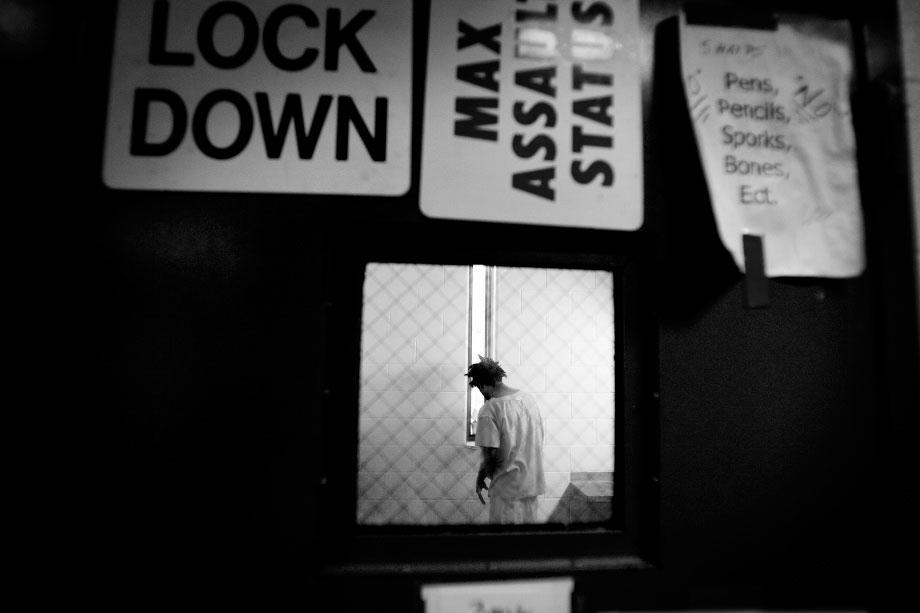

When photographer Jenn Ackerman spent her first day at the Kentucky State Reformatory for what would become the series “Trapped,” she knew she had no choice but to photograph the images in black-and-white.

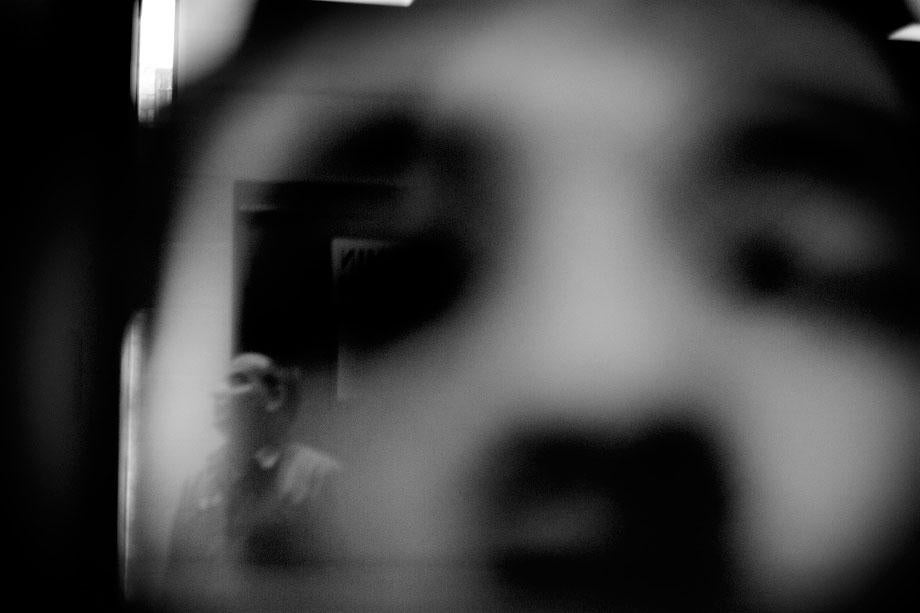

“When I went on the tour (of the prison), I didn’t see it in color; when I came back, I was trying to remember what it looked like, and I couldn’t remember any of the colors at all. I knew there was something so gritty and raw,” Ackerman recalled.

“My intention was to make the viewer feel what I felt when I was inside the prison.”

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

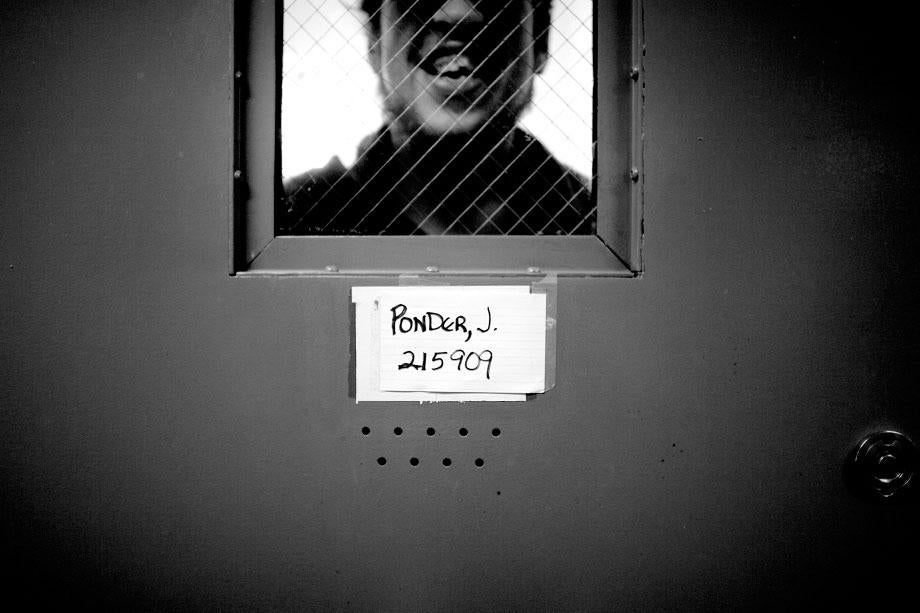

“Trapped” came about after Ackerman read an article in the New York Times on the growing population of mentally ill inmates in prisons in the United States. After her initial visit and her subsequent permission to document conditions in the prison, Ackerman moved to the area and spent roughly five days a week throughout the summer of 2008 photographing what she saw.

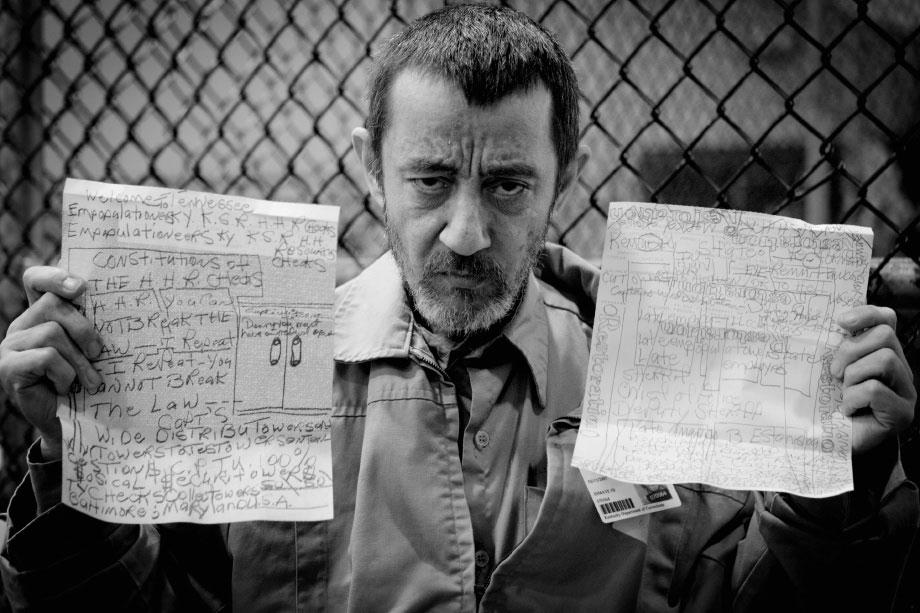

“The reason for my project wasn’t to show how terrible the conditions were in the prison; it was to [ask], ‘Is this really where we want these men to get treatment?’ We need to focus our energy on finding funding for mental health before this ever happens,” Ackerman said, noting that helping inmates psychologically isn’t the top priority; it’s security. “The only place many of these men have been able to get treatment has been in prison,” Ackerman said.

Ackerman said she has a lot of respect for correctional officers and worked hard to gain the trust of the doctors who were treating the mentally ill within the prison. Because the images are so stark and emotional, doctors were concerned it would appear that the patients weren’t getting adequate treatment.

“Once I really gained [the doctors] trust … they said they knew I was doing something to help the situation and not showing them in a bad light,” said Ackerman.

In fact, many of the images have subsequently been used as an educational training resource in prisons and law schools.

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

“You want to go into a prison and treat the mentally ill? This is what you have to deal with. They are showing people, this is the type of compassion and patience you need to have and these are the types of people you’ll come into contact with,” said Ackerman.

Spending time in the prison was both exhausting and rewarding for Ackerman and stayed with her long after she put her camera down.

“It was a project that was really emotionally draining, the most rewarding project I’ve ever worked on … my experiences and interactions with the men were good, and I missed them after the project, which was really surprising to me,” Ackerman said.