Photographer Jon Crispin first laid eyes on the Willard Asylum for the Insane in the early 1980s.

A friend who was a preservationist asked Crispin if he had ever seen the abandoned building during a drive back from a wedding by Seneca Lake in New York.

Crispin remembers clearly the moment they drove up to the 1860s building.

“It was the most evocative thing I had ever seen,” Crispin recalled. “It was sitting high above Seneca Lake on a circular driveway and it was abandoned. All my life, even as a young kid I was always interested in getting into old buildings that were boarded up, or entering places where I shouldn’t have been, and I decided I wanted to photograph it.” Eventually, this interest led to Crispin being awarded a grant from tThe New York State Council on the Arts to spend a couple of years documenting some of the 19th-century New York State Insane Asylums.

Jon Crispin.

Jon Crispin.

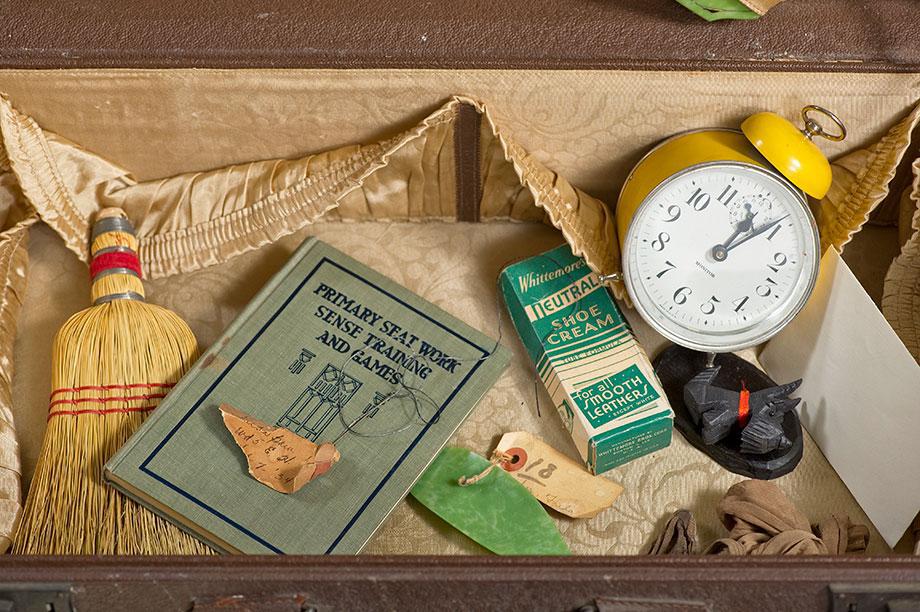

But Crispin’s fascination with the Willard Asylum was only beginning. In the mid-1990s, Willard was converted into a prison facility. An employee went into an attic of the abandoned building and discovered around 400 suitcases belonging to patients from the 1920s through the 1960s. They were cataloged and recorded and eventually displayed in an exhibition in the New York State Museum in the early 2000s, an exhibition that Crispin attended.

“I was immediately compelled by the stories they told,” said Crispin. Because of his previous connections with the asylum, Crispin was invited to photograph the cases. It was an ambitious project, and one without funding. But after reading an article about Kickstarter, Crispin was able to raise close to $20,000—enough to cover expenses and shoot the suitcases for a year.

Jon Crispin.

Jon Crispin.

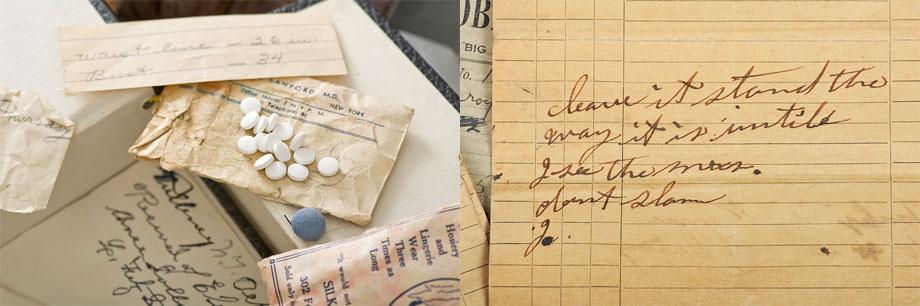

It was a fascinating, often emotional project for Crispin.

“With this project, I felt a great reverence for these people and a respect for them,” began Crispin. “It was really important for me to treat these items with a great deal of respect … it was an intense project, and I would often put my cameras down and try to feel what was going on with these objects.”

“Part of my role as a photographer is to be able to go and see things other people can’t always see and my goal is to be able to represent these items in a way that has a positive and emotional impact on people.”

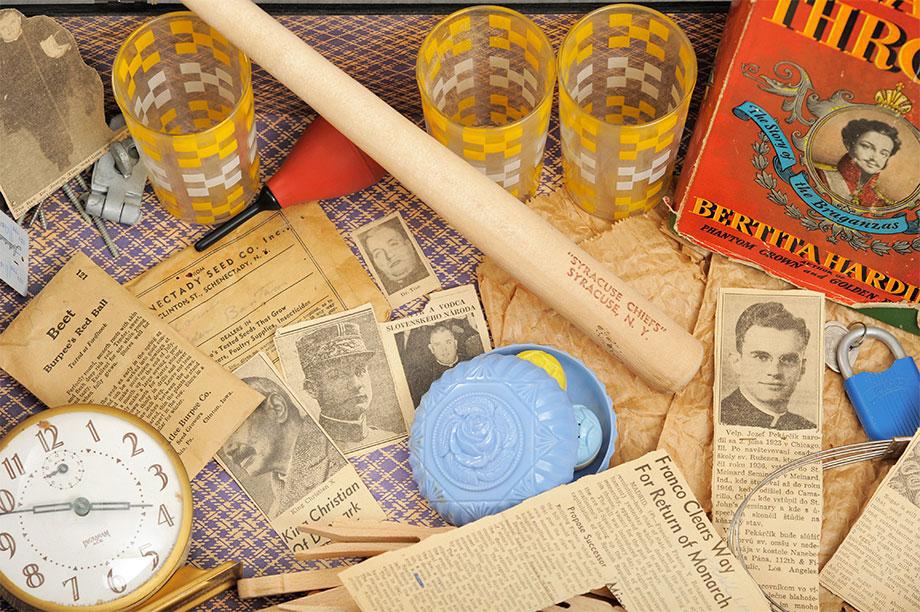

Looking through the suitcases isn’t only a peek into the personal belongings of the patients, but it’s also a time capsule of a completely different era.

“Because these people were sent to the asylum primarily through their families, the question is did the patients or their families pack the stuff?” noted Crispin.

Jon Crispin.

Jon Crispin.

Jon Crispin.

Jon Crispin.

Out of the 400 suitcases found, Crispin has shot around 80-100, stopping primarily to prepare for an exhibition at San Francisco’s Exploratorium* that opens April 17.

Crispin said that about half of the suitcases found didn’t have any items in them and not everything he looked at was as serious as the project implies.

“Some of the stuff is funny. You see odd things: false teeth out of context, for example. It wasn’t all heavy-duty, serious stuff. I think the pictures are successful because they do convey a sense of time and the struggle people had to deal with.”

Crispin said the fact that so many things were left in relatively good condition has a lot to do with the town of Willard, N.Y.

“Willard was a unique place,” began Crispin. “Small town, nothing else there but the asylum. Multiple generations of staff worked at the facility, and the staff and patients developed very close personal relationships. When the patients died, the staff just couldn’t bear to throw their possessions away, so they set up this system of storage, never really knowing what to do with the cases.”

Crispin noted that many of the owners of the suitcases were buried across the road in the Willard cemetery. Some of the suitcases were separated from the patients when they were transferred to other institutions; other times the families didn’t want to deal with them.

“There are so many questions to do with this whole story,” Crispin said.

For more information about the project, visit Crispin’s Willard Suitcase blog: http://joncrispin.wordpress.com/tag/willard-suitcases/.

Correction, Feb. 25, 2013: In this blog entry, Exploratorium was originally misspelled. (Return.)