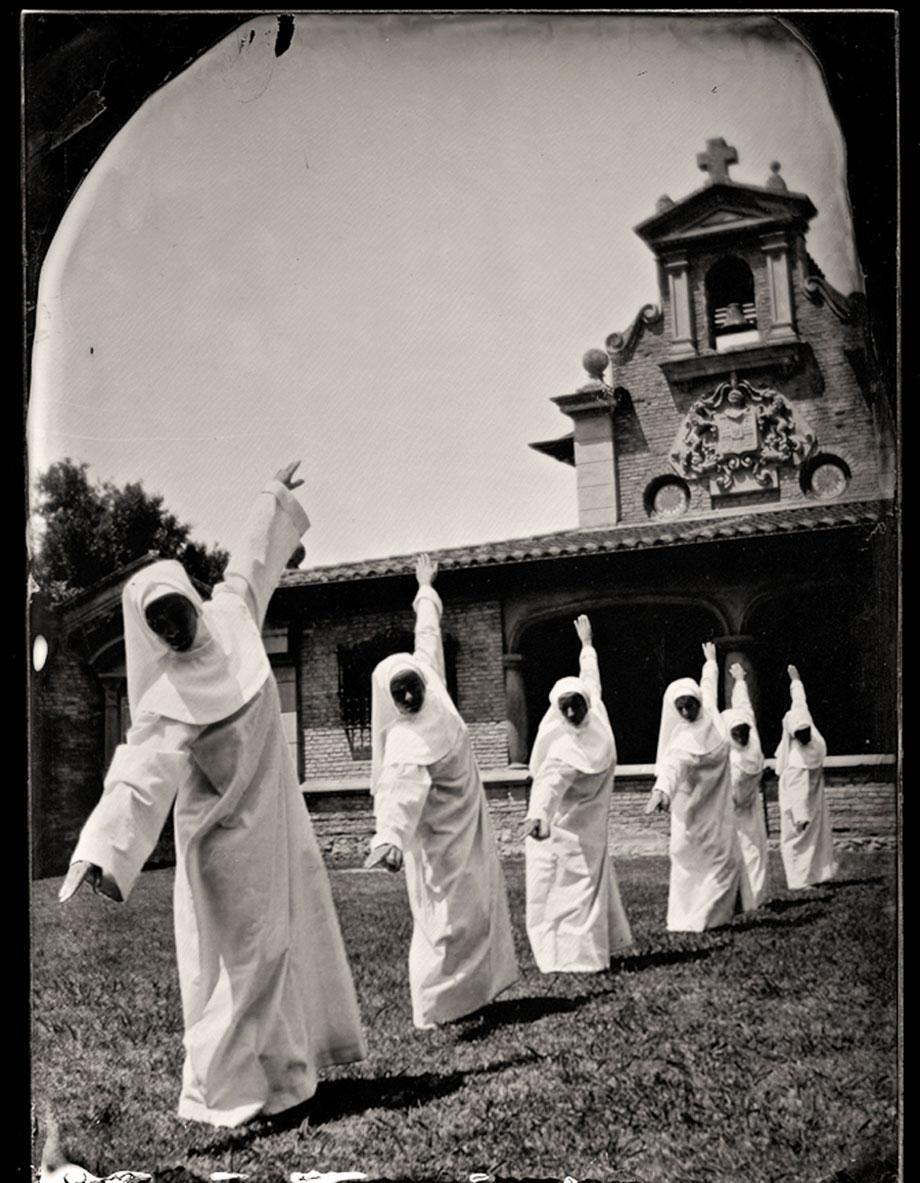

Behold is Slate’s brand-new photo blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @beholdphotos and on Tumblr. Learn what this space is all about here.

Harry Taylor.

While most photographers have transitioned from film to digital photography, Harry Taylor decided on a different route—one that led him to the mid-19th century and the world of wet plate collodion process photography.

It’s a messy, labor intensive process that involves long wait times, dangerous chemicals, and little margin of error, but for Taylor it’s pretty much perfect.

“For most people, making a great image with HDR [high dynamic range] or Instagram … is a great way to work,” said Taylor. “I work that way too, but for me I do love to see the image appear in the solution. I love the starting regime of working with big cameras, ancient optics, and long exposures.”

Taylor initially became interested in wet plates while taking care of his mother, who was sick with cancer.

During the long hours in the hospital, Taylor began rereading his favorite books about his photography heroes, including Robert Frank, Garry Winogand, and Henri Cartier-Bresson, among others.

Taylor realized in hindsight he was getting in touch with his roots and preparing for what he would do next. After his mother passed away, Taylor says, “I found a spark in the grieving that carried me to the place I needed to be.”

Initially a film photographer with a passion for 4x5 and 8x10 formats, Taylor became disenchanted when film choices began to dwindle, and he started looking for ways to work “free of corporate influence.”

Still, finding equipment and learning the new process isn’t as easy as downloading a new app. Taylor says he always stops at yard sales and flea markets to find equipment and even had two cameras made for him by hand.

Harry Taylor.

Harry Taylor.

“It’s easy to learn the basics, but as soon as you have to manage your own chemicals and make your own gear, it gets very hard. I started with a 19th-century book on the subject, but luckily I found John Coffer and a few others who helped me pull it together. After six years, I’m pretty solid, but I’m still working on perfecting formulas to get it right,” said Taylor.

Since 2004, Taylor has been documenting the Cape Fear River in North Carolina. “It’s a place of sacred memory,” said Taylor. “From the Native Americans and Spanish explorers, blockade runners … to the time this summer when a teen that said ‘watch this’ and dived in, never to be seen again; it’s flat out spooky, to this day.”

Harry Taylor.

“My visual lingo comes from dreams and fragments of visions I get from old things or interesting places. I’ve heard the tintype described as a half-remembered dream— I think that is a fair description. Because it is an object, it often gets damaged or the chemicals go wrong, but real things happen and that is a part of the whole final tintype. Also, tintypes look far better in hand than on a screen.”

Harry Taylor.

Harry Taylor.

Harry Taylor.

Harry Taylor.

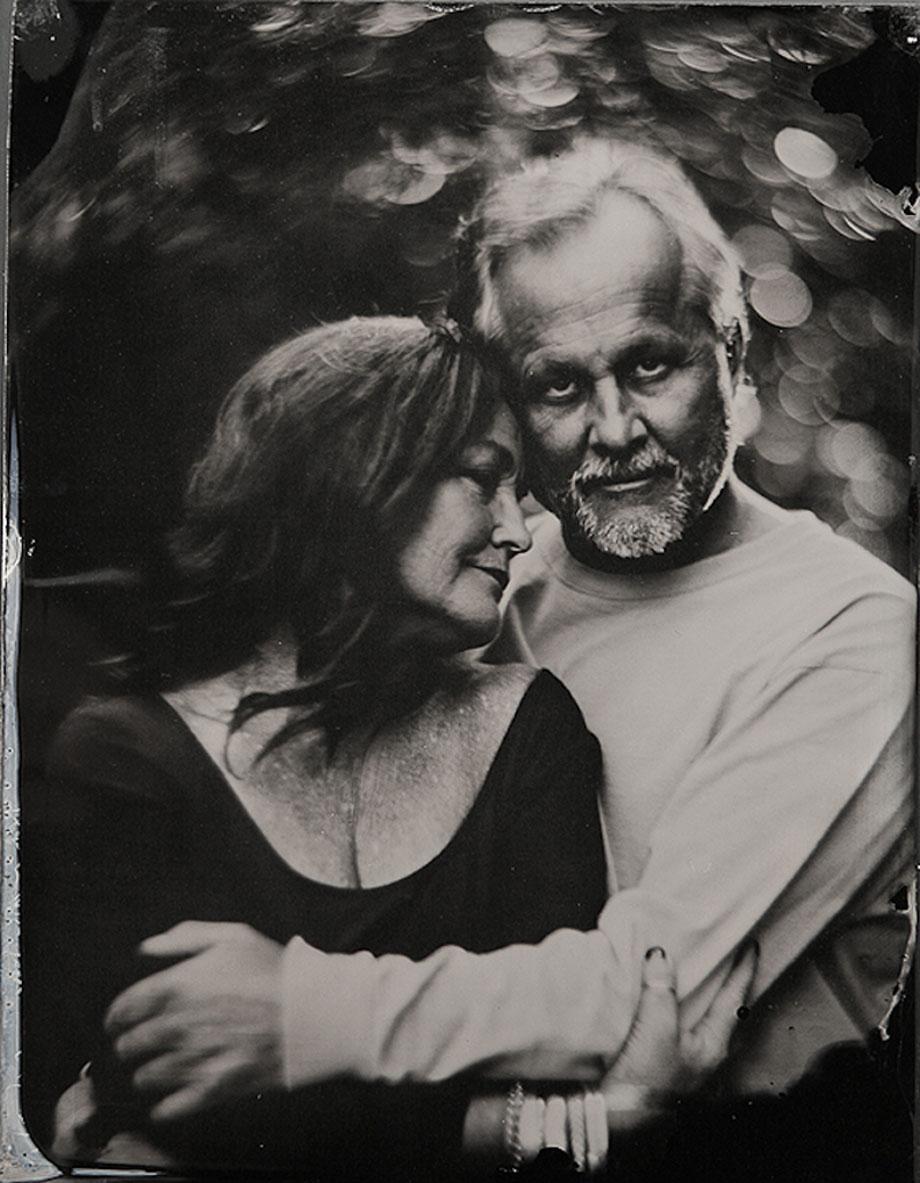

Filmmaker Matt Morris hired Taylor to shoot portraits of his fiancée Emma and him. Although the process was long—and sometimes uncomfortable—Morris came away fascinated and wanted to document Taylor’s work.

“Holding onto a smile for a 20-second exposure without moving is really difficult,” explained Morris. “You’re so focused on remaining perfectly still, in order to get a sharp photo, that you don’t realize you’ve spent the last few hours tensing up your muscles, only to find out 10 minutes later that the chemical bath was weak or the emulsion didn’t coat the tin properly and you need to give it another try.”

The collaboration led to a four-minute film Morris made about Taylor.

Harry Taylor.

Harry Taylor.

“Instead of being a subject far removed from the process, it really seems like a team effort. You want to do what you can to make sure the photo comes out right. You’re totally committed to not drifting out of focus, or blinking, or moving your head slightly. When it comes out right, you’re thrilled,” said Morris.

“I love taking photos as a hobby, and I know that far too often a good photo will get lost among thousands of images on a hard drive, rarely seeing the light of day. It’s a real shame, so I’m glad that people like Harry are out there preserving this type of photography.”