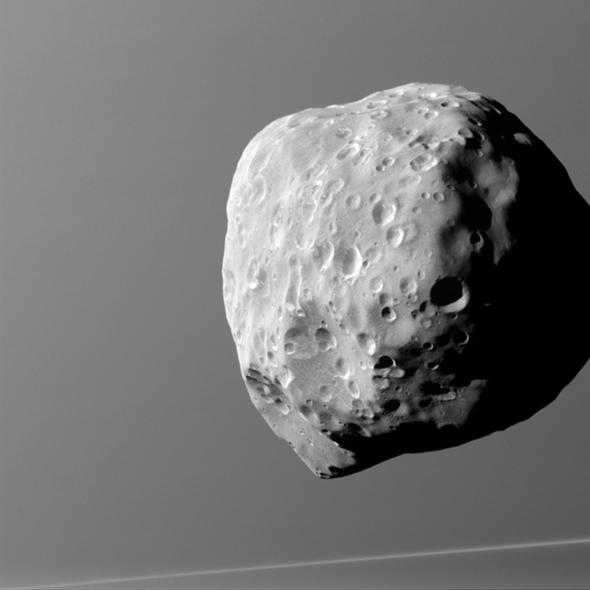

That lumpy pierogi in the photo above is Saturn’s moon Epimetheus, taken by the Cassini spacecraft in December 2015. This is a pretty cool shot; instead of the sharp blackness of space behind the moon, you see the fuzzy grayness of Saturn’s atmosphere. There’s a bit of what I believe is Saturn’s narrow F ring in the shot as well. This is an unusual geometry, giving a different perspective on the moon.

This is one of the highest-resolution images of Epimetheus that Cassini has sent back to Earth; it passed a mere 2,700 kilometers from the moon during the series of photos it took. Epimetheus is only about 115 kilometers across along its widest point, so it’s not huge (our Moon is 3,470 kilometers wide).

But it has a story to tell. It doesn’t look as sharply defined as you might expect; it has lots of dust on its surface that flows along the weak gravity to settle in low spots. The craters all look shallow, too. Some of that is from this material filling in the crater floors, but shallow craters are typical in icy bodies, where the impact energy tends to spread out more than down.

Epimetheus is weird in another way, too: It shares almost exactly the same orbit as the much larger moon Janus. Not quite exactly though. One is on a slightly smaller orbit than the other, and goes around Saturn every so slightly faster. As they slowly approach, they pull on each other with their mutual gravity. This effect gets big enough when they’re a few tens of thousands of kilometers apart that the one in the outer orbit is pulled back, dropping it closer to Saturn, while the one in the lower orbit is pulled forward, lifting it into a higher orbit. When it’s all done, the two moons swap orbits! The difference is only about 100 kilometers, but it’s enough that the moons swap roles, starting the process all over again.

Sadly, this is the last close flyby of the Moon by Cassini. It’ll pass it at a decent distance many times in the next year or two (and once as close as 6,000 kilometers in January 2017) but never again this close. In September 2017 Cassini is scheduled to end its mission by plunging into Saturn’s thick atmosphere, burning up as it sends its last few bits of data back toward Earth. This will be done to prevent it from accidentally hitting some moon in the future once the fuel has run out for maneuvers.

It’s sad, to be sure, but it’s also reason to celebrate. Cassini will have spent an astonishing 13 years orbiting Saturn, dwarfing everything we’ve ever learned about the ringed planet from before the mission.

All good things, as they say. Even all great, fantastic, and inspiring things.