So, SpaceX wants to send a spaceship to Mars as early as 2018.

Wait. Seriously?

Yup. Last week, Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX, made the startling announcement on Twitter:

He wrote, “Planning to send Dragon to Mars as soon as 2018. Red Dragons will inform overall Mars architecture, details to come.”

My very first thought when I read this was, “He thinks they can land a three-ton uncrewed Dragon capsule on Mars in the next couple of years? Something heavier than any other payload ever dropped on Mars, and from a company that hasn’t even sent anything anywhere near that far?”

Then I mulled it over for a moment. To my own astonishment, I realized, “Huh. Yeah. In fact they can do this.”

Now look, it won’t be easy, not by a long shot. But Musk’s claim isn’t out of the blue—SpaceX has been working toward this for years. What it comes down to is key pieces of technology still untested in flight but currently being developed, as well as SpaceX maintaining its current launch schedule.

But in the end, it’s feasible that in a few years, a Dragon capsule will sit on the surface of Mars*.

First, let’s take a look at the spaceship that would do the actual landing. The Dragon 2 is an upgraded version of the Dragon capsule currently being used to send supplies up to the International Space Station. Dragon V1 has been sent to space and back successfully many times already.

The Dragon 2 upgrades are extensive, including adding the ability to carry seven astronauts to ISS. But as far as a Mars trip goes, the most important upgrade is the addition of SuperDraco thrusters; four sets of two engines around the outside edge of the capsule. These are powerful, designed to be able to rapidly carry away the capsule in case of rocket failure during flight. But they’re also critical for landing on Mars.

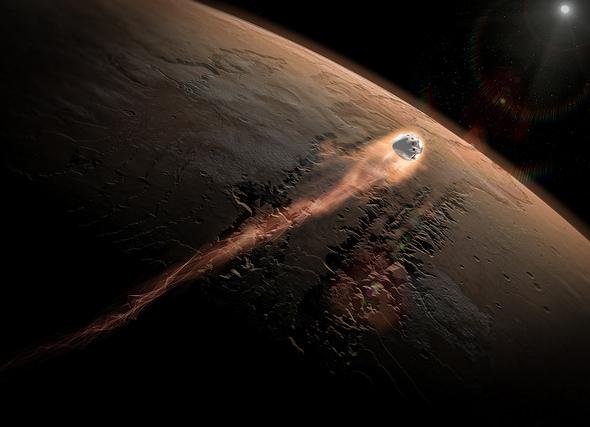

The atmosphere of Mars is very thin, but it’s there. You can’t ignore it if you want to land on the planet; at interplanetary speeds a capsule will burn up as it plows through the air if steps aren’t taken. Sending smaller probes to the surface (like early landers and rovers) used a combination of aerobraking (drag on the spacecraft to slow it down), parachutes, and in the case of Curiosity a rocket crane that slowed to a hover over the surface to deploy the rover.

SpaceX

A Dragon 2 is too big for any of these options; a parachute big enough to slow it down would be shredded under those stresses. Instead, the plan is to use an advanced heat shield on the bottom to slow it down enough that the SuperDracos can take over, landing the Dragon 2 safely on the surface.

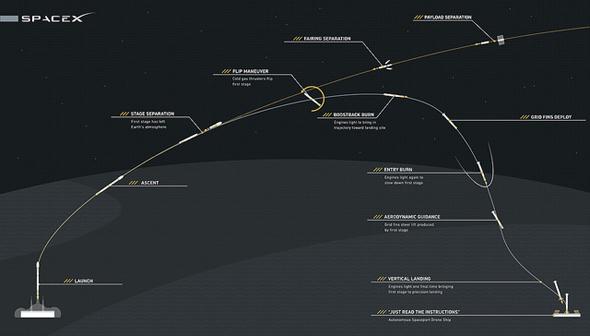

This has never been done before, but SpaceX has been slowly learning how to do it, and you’ve probably seen it happen: the return of the Falcon 9 first stage boosters. To return to Earth, the booster flips around and does a “boostback burn” to slow its motion. Even though there have been many attempts to land the booster, and only two successes, that doesn’t mean all was lost. The data retrieved from all the attempts are precious steps toward understanding how to do a “supersonic retropropulsion” burn to slow a vehicle in air … under conditions very similar to the conditions a Dragon capsule will face entering the Martian atmosphere.

That’s no coincidence. Every booster return is like a real-life simulation of a Mars landing. So SpaceX has been amassing quite a bit of information on how to do this.

In fact, they’ve been sharing that data with NASA in exchange for technical advice on deep space planning and support. No money has changed hands, just the trade of information. NASA has also pledged communications and telemetry support using their Deep Space Network in exchange for the data from an uncrewed mission to Mars using the Dragon 2.

So it looks like the Dragon 2 can get down to the surface of Mars from space. But how does SpaceX plan to get it to Mars in the first place?

Right now, the company has contracts with NASA and other groups for launches using its Falcon 9, their workhorse two-stage rocket. The Falcon 9 is a capable booster. There have been 23 launches of Falcon 9 so far, with 22 successes and one failure (that last tracked to a faulty support strut inside the booster; those have been upgraded since that time).

It can even be used to send a payload to Mars, as long as that payload has a mass less than about 4,000 kilograms (8,800 pounds, or four tons). That’s not bad, but not nearly enough to get a Dragon 2 capsule down to the surface—a dry (unfueled) Dragon 2 has a mass of 6,400 kilos.

Clearly, they’ll need a bigger rocket.

SpaceX

Enter the Falcon Heavy: This beast is essentially three Falcon 9 first stage boosters strapped together, providing a much larger payload capability. It can hypothetically send up to 13,600 kilograms to Mars. That easily covers the mass of the capsule and fuel, and would still have a few tons of capacity left for scientific instruments.

So, great. Use the Falcon Heavy to throw a Dragon 2 at Mars, and use the knowledge gained over the past few years to drop the capsule safely to the surface.

SpaceX

Except, hang on. SpaceX isn’t quite there yet. While all of this makes sense on paper, they haven’t actually tested all this hardware in flight. The Falcon Heavy has never been flown. But at the Satellite 2016 conference held in March, Gwynne Shotwell, president of SpaceX, said that the first Falcon Heavy flight may be late this year, possibly in November. That launch, from Florida, is also planned to include recovery of all three first stage boosters, two on land and one on a floating barge in the Atlantic (this is basically a three-fold test of the single booster relanding after launch). Over the next couple of years there will be more flights as well, which will hopefully work out the bugs and build confidence in the rocket.

Of course, the Dragon 2 hasn’t flown yet either. However, it has been tested extensively on the ground, including a “pad abort test,” a NASA requirement for crew-rated vehicles to make sure it can take astronauts away to safety if there’s a launch emergency:

(Click here for an amazing capsule-eye view of the abort test.)

The capsule should be tested in flight this year as well. SpaceX has said it wants to send a crew to space on the Dragon 2 in the next year or so, and already has an order from NASA to send a crew to ISS (though no date has been specified, 2018 is a decent guess).

So, SpaceX being able to go to Mars depends critically on flight-testing both the rocket and the capsule lander. But both of those tests are in the works and may happen quite soon. And, if they test successfully, SpaceX will turn its eyes to Mars.

Which brings me back to Musk’s tweet. Red Dragon is the name of the mission to send a Dragon 2 to Mars. The information learned from that mission will then be used to figure out how to send larger and more ambitious missions.

And make no mistake, Musk is determined to put people on Mars; I interviewed him on this topic in 2015, and he stated plainly, “Humans need to be a multiplanet species.”

We’re not there yet. SpaceX isn’t there yet either; quite a lot rests on the successful tests of Falcon Heavy and Dragon 2—and more, for that matter. Details of the actual mission profile (for example, what kinds of potential payloads it might carry) haven’t been released yet; the company plans on discussing all this at the International Astronautical Congress in Mexico this September. Realistically, the 2018 goal may get pushed back a year or two due to inevitable delays; there’s a long way to go and a lot to do before this mission literally gets off the ground. But SpaceX is very serious about it.

And, in my opinion, it’s quite capable of accomplishing it.

Post script: My colleague Eric Berger wrote two excellent articles on this topic: “Can SpaceX Really Land on Mars? Absolutely, Says an Engineer Who Would Know” and “Why Landing a Flying, Fire-Breathing Red Dragon on Mars Is Huge.” You’ll find a lot more details there. I’ll note we agree that SpaceX can in fact achieve this goal.

* Correction, May 3, 2016: I originally wrote that SpaceX would land a craft on Mars as soon as 2018, but that’s not precisely true; they plan on sending one to Mars then. The difference is travel time; it takes about six months to get to Mars from Earth. I updated my wording to reflect that. Also, I wrote that SpaceX hadn’t sent anything beyond low Earth orbit, but they did deploy DSCOVR which is in the Earth-Sun L1 point, 1.5 million km from Earth.

Update, May 3, 2016: Originally called the Dragon V2, SpaceX now refers to it as simply Dragon 2. This post has been udated to reflect that.