A new study just published in Nature Communications shows a worrisome trend: The number of severe tornado outbreaks is increasing with time.

Many tornadoes appear on their own, but the majority are associated with severe storms that spawn multiple tornadoes. These outbreaks can span many hours and cover a lot of territory, and are obviously extremely dangerous. They kill more than 100 people per year on average and cause billions of dollars in damage.

The study looked at tornadoes from 1954 to 2014, applying some statistical analysis to the number and strength of each. What they found is interesting, and a little bit non-intuitive, and also may have implications for the effects of climate change.

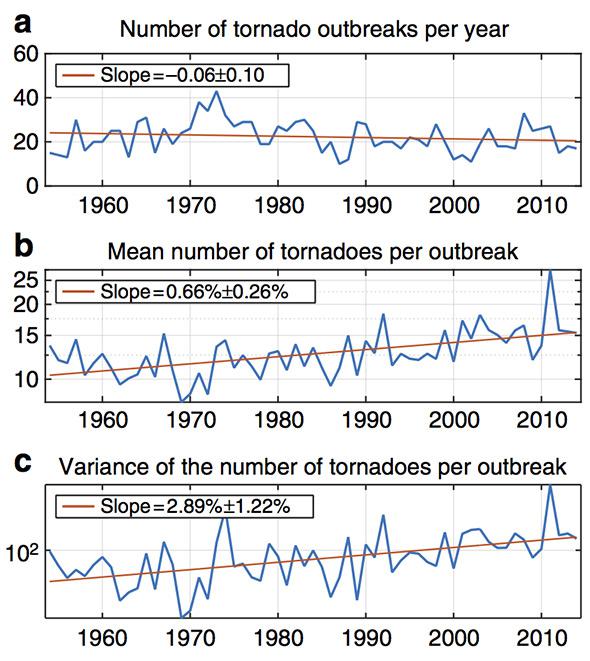

First off, they found that the total number of outbreaks per year is fairly steady across the date range, at roughly 20 per year (with lots of fluctuations year to year). The total number of individual tornadoes is also steady, roughly 500 per year (again, with lots of variation).

But that’s not the whole story. The researchers looked at the outbreaks themselves, and found that the number of tornadoes that occur in outbreaks is increasing. It’s going up by about 0.66 percent per year, from about 10 per outbreak in the 1950s to 15 today. That rise is statistically significant (that is, very unlikely to be from random chance).

In other words, we’re seeing more clustering of tornadoes in outbreaks. The researchers looked into this, and show that this is a real change in the nature of outbreaks, stating, “… the changes in the number of tornadoes per outbreak reflect changes in the physical environment.”

Something is going on with the climate that is causing outbreaks of tornadoes to be more severe. I’ll get back to that in a moment.

There’s another odd thing going on that’s a bit more subtle. The researchers looked at the variance of the number of tornadoes, too. That’s the number that shows how the number of tornadoes varies from outbreak to outbreak. If every outbreak had the exact same number of tornadoes, the variance would be 0. If some had very few tornadoes, and others had tons, then the variance would be high.

Weirdly, they found that over time, the variance itself is increasing. Comparing more recent years to the past, we’re seeing the same number of outbreaks, but we see more of them with more tornadoes each, as well as more of them with fewer. I know, that sounds odd. Think of it this way: In the past most outbreaks were close to average in the number of tornadoes they spawned, but now we see the distribution spread out; we see more extreme outbreaks as well as more with fewer tornadoes.

Tippett, M. K. & Cohen J. E. (from the paper)

That’s disturbing. That means any given outbreak might fizzle and have few tornadoes … or it means there could be far more than average. These are high stakes, and we’re rolling the dice betting double or nothing.

In general, seeing the variance in the number of tornadoes increase as the number of tornadoes per outbreaks increases is natural; it’s seen in other systems in biology and physics as well. But the variance is increasing four times faster than the mean number of tornadoes per outbreak, and that is unusual. According to the study authors, in most systems the variance increases roughly twice as fast.

Again, this implies very strongly that something is going on in the environment that is energizing these outbreaks.

The obvious something to consider is global warming. Storms use heat as fuel; it causes more evaporation of water and stronger convection, both of which are critical to generate storms. Increase the heat content of the atmosphere and that will have an effect on storm generation.

Scientifically, though, we cannot pin this new result on global warming just yet. But it’s certainly a prime suspect! More evidence is needed. As one of the researchers, Joel Cohen, put it:

Variance is growing faster than I would have guessed, and we don’t know why it’s so different from what we find elsewhere. If I were to speculate, I would say that certain physical drivers are accelerating, leading to increased energy in the atmosphere, which affects the forces behind tornadoes. Our results do not directly link climate change to the increasing severity of outbreaks, but we’ve found an indicator of change that’s hard to explain otherwise.

This reminds me of the study showing an increase in top wind speed in hurricanes over time. The number of hurricanes isn’t increasing over time, but the top speeds of the most severe ones are getting faster. Global warming is certainly behind that, but the environment in which hurricanes grow is complex (for example, wind shear can curtail their growth). This sounds a lot like what we’re seeing here. The environment to grow a tornado is also complex, and global warming may stir that up further, so we see the same number of tornadoes overall, but outbreaks are getting worse.

I suspect this study will be cited by climate science deniers, and that they’ll look no farther than “the number of tornadoes hasn’t increased” (one thing you can always count on with deniers is that they will cherry-pick their data). But the total number is not the whole story. Climate is complex, and subtle. We can’t just stick our noses outside, say, “It’s cold outside” and deny what’s happening to our planet.

We have to learn to read the nuances, find the connections, understand the underlying principles. The good news is, that’s precisely what scientists are doing.

The bad news is, getting this through to the politicians is nearly impossible … except in November. It would be nice to see the climate science deniers in Congress have to weather that storm.