We may have a new cosmic record-breaker: A galaxy discovered in 2013 may be the most distant galaxy ever seen. And I do mean distant: If the research is correct, the light we see from it left now the galaxy 13.3 billion years ago. Incredibly, we’re seeing it as the very first stars in the Universe themselves were forming!

To be clear, I think this observation looks pretty good. But there’s always room for a little skepticism, and the observation itself and the analysis they did on it is right at the edge of what’s possible, even for Hubble. No doubt this galaxy will be an early target for the James Webb Space Telescope once it’s launched in 2018. Until then, though, getting solid confirmation of this record-breaking galaxy’s distance may not be possible.

So what have we got here?

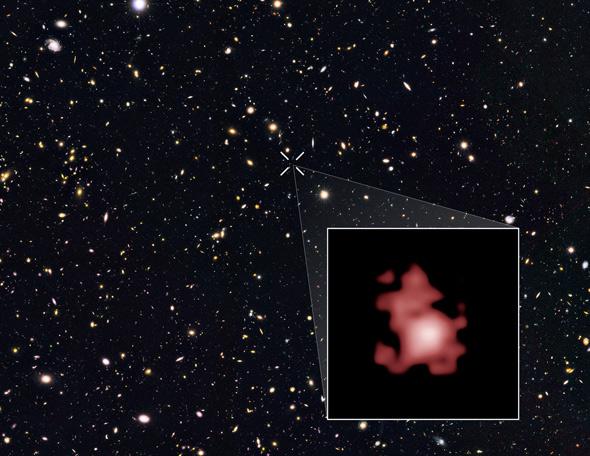

The galaxy, nicknamed GN-z11, was spotted near the bowl of the Big Dipper as part of a survey looking for extremely distant galaxies. Using Hubble, astronomers stared at five small spots in the sky using Hubble’s powerful Wide Field Camera 3, which is sensitive to infrared.

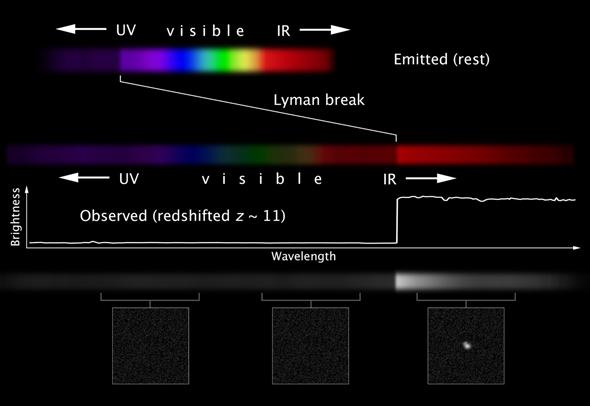

This part is the kicker: Very young galaxies should be blasting out ultraviolet light as newly born massive stars flood nearby space with energy. But these galaxies are very far away, so far that the light from them has to fight the expansion of the Universe itself to reach us. The light loses energy, and by the time it gets to Earth that ultraviolet light has redshifted into the infrared. Hence the infrared survey using Hubble.

There’s more. Hydrogen gas loves to absorb ultraviolet light. Well, up to a point: If the light has too much energy, it blows the electron off the hydrogen atom, and the atom can no longer absorb any light. Any ultraviolet light with more energy than this doesn’t get through the hydrogen, and so if we take a spectrum of the light (breaking it up into colors) the amount of light drops precipitously at that energy. This is called the Lyman break.

But if that light is coming from a galaxy far, far away the Lyman break gets redshifted, too, and we see it in the infrared. So if you take a bunch of pictures of the galaxy using different filters, you see it in some of the images, and not others. By looking to see where the galaxy disappears you can estimate its distance (the farther away it is, the farther into the infrared the Lyman break is redshifted). I explain this in more detail in an earlier post.

NASA, ESA, and C. Christian and Z. Levay (STScI)

Back to our distant record galaxy GN-z11: Preliminary measurements indicated it was redshifted by a factor of 11 (what we astronomers call a z=10 galaxy), making it the most distant galaxy seen in the survey, and one of the most distant seen ever. This made it a good target for follow-up, so they used 12 orbits of Hubble time (that’s a lot) to reobserve it using a spectrometer, which can yield more accurate redshifts. This was a tough observation, because the galaxy is faint, and nearby stars and galaxies contaminate the sky around it. They had to do some pretty sophisticated data analysis to tease the galaxy light out of the sky.

But when they did, they got their surprise: The galaxy was at a z of 11.09, meaning it was a staggering 13.3 billion light-years away.

Let me say, wow. That’s a long way off. And that’s also a very interesting distance to find oneself at! Why? Because it’s just about 400 million years after the Big Bang, which is just when we think stars first started forming! The light we’re seeing from this galaxy may in part be from the very first generation of stars the Universe ever saw.

How about that? Not only that, but it looks like the galaxy had already been making stars for a while; using various models of how galaxies are born and form stars, it looks to be about 40 million years old. And it’s cranking them out, too: Models indicate it’s forming stars at a rate of about 24 times the mass of the Sun per year, which is a lot. Our own galaxy only manages to make about one solar mass worth of stars per year, so GN-z11 is making them two dozen times faster.

Overall, it has a mass of about a billion or so times the mass of the Sun. That’s small (the Milky Way has a mass of roughly a trillion Suns), but not too surprising: It’s young. We’re only seeing the light from the stars that it’s already made. There could be a lot more material floating around it, waiting to get turned into stars.

The next question, assuming this all pans out, is: How many galaxies can we expect to find at this distance? GN-z11 is unusually bright, it so happens, so most galaxies at this distance are too faint to be seen. The authors looked at the numbers and found that given what we know about how bright galaxies are, ones this bright are very rare, so it’s highly unusual they even saw it at all in the survey. That makes me mildly suspicious; either they got very lucky, or the physics of how galaxies behave at this age isn’t as well understood as we thought.

I hope it’s the latter. Getting lucky is nice, but if you’re a scientist finding out there’s something you’ve missed is way better. More to learn! More things to find! More understanding to be had!

In fact, I’d say those are pretty good reasons to look for distant galaxies in the first place.