A new image of Pluto was sent back to Earth from the far, far distant New Horizons space probe, and it’s a doozy: It shows Pluto from the other side, backlit by the Sun. While we’ve seen pictures like that before, this one is in color.

And it looks like Pluto’s sky is blue.

But is it? Well …

The blue ring around Pluto in the picture is due to what’s called scattering. Teeny tiny particles are suspended in the atmosphere of Pluto, and when sunlight passes by them, the red light gets through, but the blue light hits those particles and caroms off in a different direction. The Sun is not directly behind Pluto in this picture—it’s off to the upper right, which is why the ring is brighter in that direction—so the light we see consists of the blue part of the spectrum, scattered around and sent toward the New Horizons camera.

On Earth we see the same thing, and it’s why our sky is blue. In our case, it’s nitrogen molecules in the air (which, after all, is 78 percent nitrogen) that do the scattering. For Pluto, it’s probably from a haze of stuff created when the Sun’s ultraviolet light breaks up simple molecules, which then recombine to make more complex stuff. It’s not yet understood what molecules are creating the blue ring, though.

So, if you stood on Pluto, would you see a blue sky?

Well, no. Not really. It’s not like Pluto has a lot of air. The atmospheric pressure on its surface is only about 0.00001 times that of Earth’s! Even if it were warm and had oxygen, you’d suffocate just as quickly as if you were standing on the surface of the Moon.

But assuming you had a spacesuit with a really good heater, the sky would look pretty black. However, at Plutonian sunrise or sunset, it’s possible that there’s enough atmosphere to see a thin blue line near the Sun on the horizon. I’m not sure your eyes would pick it up but a camera might. Update, Oct. 9, 2015: I’ve been talking with my pal and New Horizons team member Tod Lauer, who pointed out that although it would be fainter than on Earth, the haze in Pluto’s atmosphere should be visible to the human eye around sunset/sunrise, and might very well give the sky a blue cast there. I’m inclined to agree with him; he pointed out that images of a crescent Pluto show the haze is visible above the surface (and even very softly illuminates the surface), and the human eye should be able to pick it up near the horizon. I’m pretty sure the sky would look black above you fading to blue near the horizon, but it’s unclear how that transition occurs. That would be a very interesting calculation.

Thinking about this made me curious: How long would sunset last on Pluto? By this I mean, once the bottom edge of the Sun touches the horizon, how long will it take the full disk to disappear?

On Earth that takes about two minutes (neglecting our atmospheric effects, which make it act like a lens and can mess with the timing).

But Pluto is so far away that the Sun’s disk appears to be only about 1/40th as wide as it is from Earth on average (Pluto’s orbit is highly elliptical, so sometimes the Sun will look much bigger or smaller than average, but let’s go with this).* That by itself will make sunsets faster.

Pluto spins much slower than Earth does, once every 6.4 Earth days, so the Sun will move more slowly across the sky than it does here. But that’s not enough to make up for its tiny disk. Once the bottom of the Sun kisses the horizon, it’s all over about 20 seconds later.

So if you can see any blue to the sky, right around the horizon, you’d only have about that long to appreciate it. Update, Oct. 9, 2015: New Horizons PI Alan Stern sent me a note pointing out that while the Sun might only take 20 seconds to physically cross the horizon, due to the scattering in the atmosphere twilight on Pluto before sunrise and after sunset might last for many hours. This ties in with the conversation I had with Lauer above. And another thing: Lauer pointed out that Pluto is tilted so much that it’s nearly north-pole-on to the Sun, so if you’re on the terminator, the day/night line, the time it takes the Sun to set can be much longer right now! I was just playing with numbers above and hadn’t even thought of that. This is clearly more complicated than I had first supposed, though just how complicated still isn’t clear! But it shows that no matter how you slice it, sunset on Pluto would be pretty amazing to watch.

Photo by NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

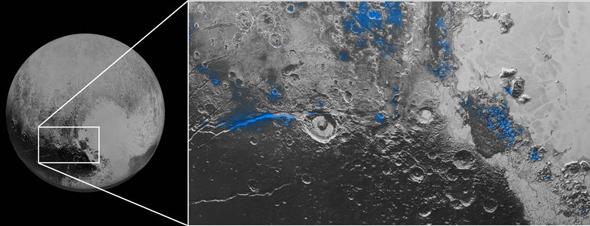

Another interesting image was also released, and it shows the location of water ice on one small part of Pluto’s surface. Pictures alone won’t give that information, but New Horizons has a spectroscope on it, which breaks light up into many individual colors. Different substances have different spectral signatures, so they can be differentiated from one another. That’s how the water ice was mapped.

Interestingly, in this area it’s only seen in those shallow craters near the top, and a few other areas. Very interestingly, all these regions are red. That’s probably due to the presence of tholins, complex organic (carbon-based) compounds that are created in the same way I described above, when sunlight lets molecules rearrange themselves.

Why would water ice be where the tholins are? That’s a good question and the planetary scientists have been asking themselves that same thing. They don’t know. But like everything else in these images, it’s a clue telling us about what Pluto’s doing: what it’s made of, how that material moves around, how it interacts with other material and sunlight, and maybe even hinting at past geological processes.

After all, that smooth region to the right (informally called Sputnik Planum, the left part of the heart-shaped area) doesn’t seem to have any water. It’s thought to be a sheet of nitrogen ice that probably moved glacierlike over the lowlands, stopping where the elevation got higher. At Pluto’s temperature, water ice is harder than solid rock here on Earth, so I wouldn’t necessarily expect it to be there on the plains. It won’t flow! But why is it in the highlands, in spotty areas? No one knows.

Yet. We’re learning more all the time, something new every time a new batch of data is sent back. And even when we get it all, it’ll be years before it’s all analyzed. And also, don’t forget that the spacecraft may fly by a Kuiper Belt object called 2014 MU69 in January 2019—it’s been selected as a new target, but hasn’t been given the official NASA go-ahead yet. But if it is, then we’ll get to do this all over again with a new object.

Well, new to us. It’s actually more than 4 billion years old. What delights await us when we see that up close?

*Correction, Oct. 9, 2015, at 17:00 UTC: I originally misstated that the Sun would look 1/30th as large from Pluto on average than it does from Earth, but it’s actually closer to 1/40th. The rest of the math I did is correct. Thanks to my friend and colleague Don Goldsmith for pointing this out to me.