On Tuesday, NASA announced the scientific research instruments that will be installed on board the 2020s mission headed for Jupiter’s moon Europa.

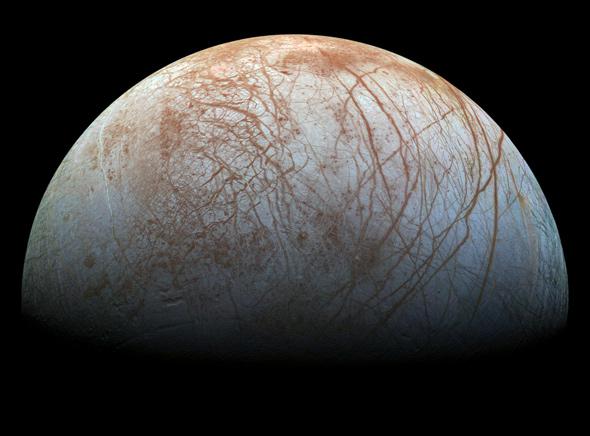

The moon has a thick ice shell covering an undersurface ocean, and there’s a lot of interesting chemistry going on in that water. We don’t know if there’s life there, or even if the ocean is habitable, but it’s an incredibly enticing destination. That’s why the (currently not-yet-named) mission is headed that way.

And it’ll have quite the suite of instruments onboard, too: a camera that will map almost the entire moon with 50 meter resolution (and some spots with 0.5 meter resolution!), radar that can determine the thickness of the ice and ocean, a thermal (heat) mapper, an ultraviolet camera, and much more. You can read about them on the NASA press release and in the Planetary Society blog post by Casey Dreier.

I’m excited about this; the NASA fiscal year 2016 budget has $30 million set aside to develop the mission. If things go well, there will be more in the years to come. Europa is one of the three best places to look for life in the solar system—the other two being Saturn’s moons Titan and Enceladus, and a mission there would take longer, be bigger, and cost more money. As much as I want to see more of those worlds, I think going to Europa is a good first step. And if we do find something biologically intriguing there, we’ll be in a better place to send more missions.

Now pardon me while I take something of a left turn.

I follow quite a few planetary science folks on Twitter, and it was Christmas for a lot of them on Tuesday. My feed was nonstop chatter about the science that’ll be done at Europa. Someone mentioned that of the nine instruments chosen for the mission, three of them have women as principal investigators (the person in charge of the project). I checked, and sure enough, it’s true.

Female PIs are not exactly unheard of in NASA, but they’re certainly not at a 50-50 ratio with men (I worked on the proposal for the NuSTAR mission, the first NASA astrophysics observatory with a woman at the helm, and that launched just three years ago). There is nowhere near parity in the sexes at most scientific institutions, so I like to support and highlight women in the field when I can (for example, Sally Ride’s birthday on Tuesday).

So in the interest of raising a bit of awareness, I tweeted about it:

Seems clear enough. But I got a couple of angry tweets in response; both accused me of being sexist, seeming to think I was somehow amazed that women could actually run NASA science instruments!

Um. I know that we live in an outrage culture, and I also know just how things get misinterpreted on the ‘Net. Even so that struck me as a bit of a stretch.

I followed up the tweet with another one expressing my own bafflement as to how I could be accused of that when I was supporting women (especially given the context of my many tweets and blog posts supporting women in STEM), and then got responses saying those first responses must’ve been from, gasp, feminists.

At that point my desk got up close and personal with my forehead. I think pursuing this line of thought is going to lead to an ever-amplified Möbius strip of hollering Internuttery, so I’ll leave it to you to follow it if you so choose. Tread carefully.

But this whole thing brought up a point that is worth thinking about. As I said, in most sciences there isn’t parity between men and women. Study after study show that this must have some sort of social basis; women are no less or more suited for science than men. I am no expert on the details, and I leave that for those who are doing the research to investigate. But the conclusion remains.

In an ideal world, science would be science, and anyone of whatever sex who does it for the betterment of humanity is fine by me.

But we don’t live in an ideal world, and we must be practical. Women are not staying in sciences, they aren’t treated the same as men (and it’s generally in a negative sense, unless you’ve been living somewhere under the crust of the Earth for the past, oh, say, century or two), and they are at a disadvantage in many ways compared with their male colleagues. Not an intellectual disadvantage, not a performance disadvantage, not any intrinsic disadvantage, but a socially-engineered one.

If all things are equal except for the societal thing, then how about we fix the societal thing?

One way to do that is to simply make people aware of it. I’m not exactly the swiftest boat on the lake when it comes to things like this, and it took me a long time, but I’m coming around to the notion that sexism pervades everything in our culture.* If I can figure that out (due to the raising of my own awareness by my friends and colleagues), then so can others, and if I can help, well then I will.

And so I do what I can. There may come a time when parity or a close approximation thereof can be achieved. When that day arrives then we won’t need to note when women make strides toward equality, and an achievement in science will be simply that, rather than segregated by the sex of the achiever. But that day is not yet here.

In the meantime we can all work toward it, and work toward the bigger goals of science at the same time. And when we do, we need to remember the mistakes of the past, so that we don’t repeat them—social equality is a dynamic equilibrium; we need to keep working at it to maintain it, lest the scales tip once again.

There are entire worlds to explore out there, folks. Let’s do what we can so we can all explore them.

*It’s more fair to say that sexism is one of the main biases pervading our culture, along with many others such as racism, homophobia, and a host of other prejudices. That list goes on and on, and it might be easier just to say there’s a bias against anything that isn’t white-cis-Christian-middle-class-male, but I don’t want to lose the main point here.