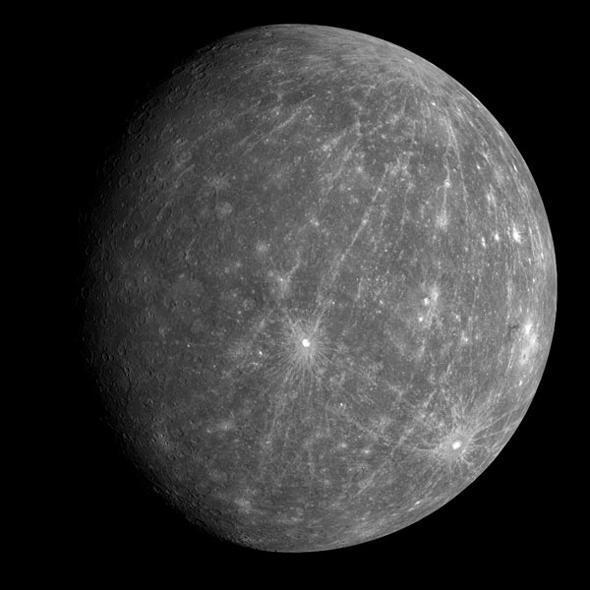

Mercury is an airless rocky world, much like our Moon, but for some reason it reflects less light than the Moon. This lower reflectivity (what we science types call its albedo) makes it darker than expected.

For a long time, it was thought that small grains of iron were the culprit. Being near the Sun, Mercury is cooked by light and subatomic particles from the Sun. This creates these tiny iron grains from iron embedded in the surface material, and these grains are quite dark. However, it turns out there isn’t enough of them to explain why, on average, Mercury reflects half the light the Moon does.

A new study has turned up a new perp: carbon. Comets have lots of carbon in them, and as they swing by the Sun they release a lot of it into space. In fact, as they get closer to the Sun they release more (especially ones that disintegrate completely, which does indeed occur often), so Mercury should get a big dose of carbon.

To test this, the scientists used a powerful gas gun at NASA’s Ames Research Center (my old pal Pete Schultz is a co-author on this study; we used that gas gun for an episode of Bad Universe). They shot pellets at several kilometers per second into a target of dark basaltic rock that also had sugars mixed in it (as a carbon source, mimicking carbon-based molecules in a comet). They found that carbon could be freed from the sugar molecules and mixed into the resulting melted impact material, making it darker.

The basaltic rock was more like the Moon’s surface than Mercury, but the results are encouraging. My very first thought about this as I read the report was, “What about a spectral signature of carbon?,” meaning that if carbon were there on Mercury’s surface, why don’t we see it in spectra (breaking the light up into thousands of individual colors, allowing the chemical composition to be determined)? They covered this as well: The spectrum of the impacted material in the experiment was fairly flat, with no real hint of carbon embedded in it. The carbon was mixed into the material in a way that hid it spectroscopically, even though it absorbed light and darkened the rock.

Is this why Mercury is darker than expected? Maybe. More tests and observations are needed; the lack of a spectral signature is interesting but not in itself proof. Still, it’s kinda neat to think Mercury might be dark because it’s painted with carbon atoms, airbrushed over the eons by the breath from comets.

The surface of Mercury may be harsh, but maybe it got that way poetically.

*None. None more black.