On the afternoon of Thursday, Oct. 23, 2014, the Moon will pass in front of the Sun.

What we’ll see is a partial solar eclipse, where the Moon passes along a chord of the Sun’s face, never completely blocking it out. At maximum eclipse the Sun will look like a thick crescent, the dark disk of the Moon moving across it.

This is a very cool event, and it favors Canada and the United States; it’ll be visible in nearly the entirety of both countries. The exception is the extreme northeast, where the Sun will be setting as the eclipse starts (whether you see anything or not from that area depends on your exact position; see below).

Fairly Warned Be Ye, Says I

First, let’s get this out of the way: NEVER LOOK AT THE SUN WITHOUT PROPER FILTERS. You probably won’t do severe or permanent damage to your eyes by glancing at the Sun with your eyes alone, but I’d advise against it (especially for younger children, who have clearer lenses in their eyes that let through more damaging UV light)—and certainly against anything longer than a very brief glance.* AND DON’T EVER EVER EVER LOOK AT THE SUN THROUGH A TELEPHOTO LENS, BINOCULARS, OR A TELESCOPE without proper filtration, and honestly, unless you really know what you’re doing, just don’t do it.

You might think sunglasses are OK, but they’re generally not. They can make it worse; they block visible light from the Sun, so the pupil in your eye widens. That can let in more harmful UV and infrared light.

If you want to see this event properly and safely—and you should, because eclipses are very cool—I urge you to find a planetarium, observatory, or local astronomy club near you and let experts handle the equipment for you. They might even have a pair of eclipse glasses you can use. (It’s too late to order ones now, but there will always be more eclipses so I suggest you order some; they’re cheap.)

I have more about safely observing the Sun in a post about the Venus Transit from 2012; I strongly urge you to read it before going out to take a look.

OK, So What Does All This Mean?

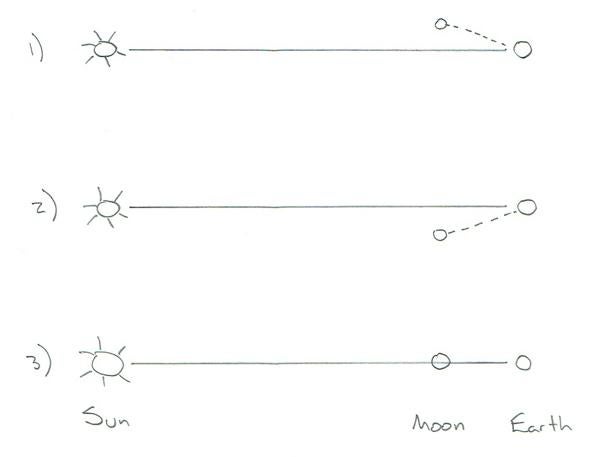

Here’s how this works. The Moon orbits the Earth once per month, and the Earth orbits the Sun once a year. The Moon’s orbit is tilted to Earth’s orbit by about 5°, so as it goes around the Earth it passes through the Earth’s orbital plane every two weeks or so. If the Moon’s orbit weren’t tilted, we’d get a solar eclipse every month when the Moon passed between the Earth and Sun. Since it is tilted, though, sometimes it’s “above” the Sun at new Moon, and sometimes “below.” We only get eclipses rarely because the Moon has to be crossing the plane of Earth’s orbit at the same time as it’s new Moon, so that it gets exactly between us and the Sun.

Diagram by Phil Plait, artiste extraordinaire

On Oct. 23, the geometry is close but not quite perfect. Instead of passing directly in front of the Sun, cutting straight across it, the Moon passes the Sun at an angle off-center, so it only partially blocks our star. That’s why this is a partial eclipse, and not a total one.

In a lunar eclipse, the Earth gets between the Sun and Moon, and casts its shadow on the Moon. The event happens on the Moon, so everyone on Earth facing the Moon sees it at pretty much the same time.

But a solar eclipse is the Moon casting its shadow on Earth. The Moon is moving, orbiting us, and the Earth is rotating as well, so what you see and when you see it depends on where you are. (It’s like sunset, which you see at a different time than someone east or west of you.)

Animation by Fred Espenak/NASA

On the left is an animation showing the view from above the Earth, looking down on the U.S. during the eclipse. The curved line sweeping around clockwise is the terminator, the day/night line. The big gray distorted circle is the physical shadow of the Moon. You can see that over time it moves roughly eastward and southward, the combination of its motion and the Earth’s spin. If you live anywhere inside the path of that shadow, you’ll see an eclipse. The closer you are to the center of the shadow, the more of the Sun will be blocked.

So when will you see it? If you happen to live near a big city, here’s a table showing eclipse times, and there’s also an interactive page where you can enter your location and it’ll tell you when the eclipse happens.

As an overview, here’s a map showing timing and percentages of the Sun blocked.

Drawing by NASA/Fred Espenak

It looks daunting, but it’s not that hard to interpret once you get used to it. The more-or-less horizontal curves are marked 0.20, 0.40, 0.60 and 0.80; those are telling you how much of the Sun is blocked. I’m in Boulder, Colorado, just south of the 0.60 line, and so the most I’ll see is about 56 percent of the Sun blocked. That’s not enough to really notice it getting any darker out.

The more-or-less vertical lines tell you the time of greatest eclipse in UTC (subtract 4 hours for Eastern, 5 for Central, 6 for Mountain, and 7 for Pacific times). Boulder is just to the east of the 22:30 UTC line, and for me I’ll see the most amount of Sun blocked (what’s called greatest eclipse) at about 22:34 (16:34 or 4:34 p.m. local time).

Viewing and Photographing the Eclipse

First off, again, here are some tips on how to safely observe the Sun, and you can find a lot more here. I’ll reiterate a few here.

If you have certified eclipse/solar viewing glasses, you’re OK. These are designed to block the dangerous IR and UV light from the Sun, while cutting way down on the visible light. The Sun looks like a small disk, and the eclipse will look really cool just like that. Again, don’t use sunglasses, even if they are UV blocking! They can actually increase the damage to your eyes.

I’ll add here that there is a monster sunspot (AR 2192) that is crossing the Sun’s face right now, and that’ll make a very dramatic feature to see during the eclipse.

If you have a pair of binoculars you can use them to project the Sun on a piece of white paper. Again, seriously, don’t look through them at the eclipse unless boiling your eyeballs is something you’re hoping to do. Also, be warned: The Sun can heat up the inside of your binoculars, and can damage them. I’ve used this technique many times with no problem, but I have pretty decent equipment. Plastic lenses, for example, might not fair well. Proceed at your own risk.

First, block one of the big lenses with a lens cap or something opaque, so you’re only using one half of the binoculars (otherwise you get two images). Get a big piece of white paper (poster board is great for this) and prop it up facing the Sun. Hold the binoculars so that you can see the shadow of them on the paper. Orient them so that the shadow of the binoculars is as small as possible; when they’re aligned with the Sun you’ll see an image of the Sun on the paper. Move the binocs toward or away from the paper to get the Sun the right size, and focus them. This takes some practice, but after a few minutes you’ll get the hang of it.

You can also do a variation of this projection method with a telescope, but I really, really don’t recommend it. ‘Scopes gather a lot of light and focus it down into a tight beam, and that can severely damage eyepieces and/or the telescope itself. And NEVER use one of those little “Sun filters” to screw into your eyepiece! Those can heat up and crack, and under some circumstances shatter, sending glass shard outwards at high speed. Not a good idea.

If you happen to have a telescope with a Mylar Sun filter that goes over the front end of the ‘scope then you’re probably OK. Just make sure you know what you’re doing. I’d hate to see anyone get hurt, or equipment get damaged, from observing the eclipse.

And finally, if it’s cloudy where you are, don’t despair! Eclipses are always live-streamed from various locations, so you’ll be able to watch it on your computer. The Coca-Cola Space Science Center will have a webcast, and I’ll add more here as I find out about them.

Update, Oct. 22, 2014 at 04:00 UTC: My friend and astronomer Adam Block is doing an eclipse live stream from the Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter in Arizona. This should be high on your list! That’s a great location and observatory.

Update, Oct. 23 at 15:00 UTC: Griffith observatory in L.A. will be open to the pubic for observing the eclipse and will also have a webcast.

Update, Oct. 23 at 16:30 UTC: My friend Scott Lewis is doing a live webcast of the eclipse; you can find links at the Know the Cosmos website.

Update, Oct. 23 at 19:30 UTC: The McMath-Pierce solar telescope will be providing live vews of the eclipse from the Kitt Peak Observatory. Thanks to my old friend Rob Sparks for the tip!

The next solar eclipse is on March 20, 2015, visible from Europe and Asia; the next one visible from the U.S. will be the great total eclipse of Aug. 21, 2017, which will cut right across the heart of the country. That one will be a big deal.

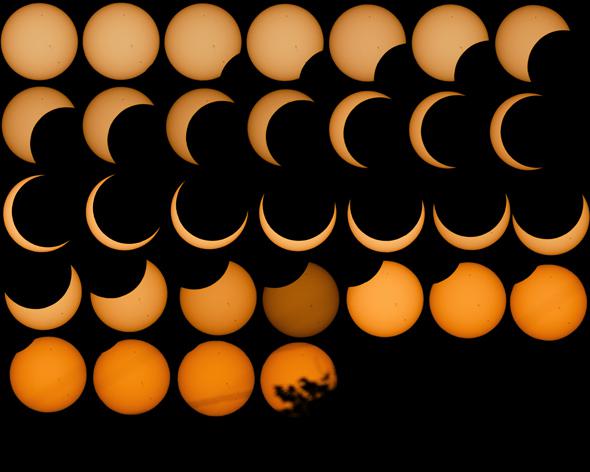

So if you’re in North America, try to catch this one; it’ll be three years before the next. There’s something wonderful and, yes, other-worldly about eclipses, even partial ones. If you get a chance to watch (safely), take it. And if you do get pictures, send me links (either via email, or on Twitter)—I’m hoping to put up a gallery of the most clever and cool ones. I have a gallery from the May 2012 solar eclipse that might give you some inspiration.

*Update, Oct. 22, 2014 at 04:00 UTC: I originally wrote, “You probably won’t do severe or permanent damage to your eyes by looking at the Sun with your eyes alone…” and should have been clear that simply glancing is likely not a problem, but looking for longer could be.