Yesterday, comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) zoomed over the surface of the Sun, barreling through the star’s intolerable heat and light. We all waited on the edge of our seats to see what would happen, and amazingly, a few hours later, something came out the other side.

But what, exactly? We’re still not sure. But here’s my guess, based on what I’ve seen and heard.

Sun Diving

Let me give you a quick overview first. The comet itself was a chunk of rock, gravel, and dust held together by ice, smushed into an object perhaps two kilometers (a bit over a mile across). It came from the Oort cloud, a vast repository of such icy chunks well outside the orbit of Neptune. The orbit of ISON is extremely close to an escape trajectory for the solar system, meaning this is likely its first and only dip into the neighborhood; it may not ever return, and instead be ejected into interstellar space (or at least not be back for many, many, millennia).

As it approached the Sun on Nov. 28, it suddenly got very bright, which could have been from an outburst (perhaps due to solar heat seeping under the surface, reaching a pocket of ice, changing it directly from a solid to a gas, and triggering a sudden expulsion of that gas as it expanded), or even a disruption event. Since the ice holds the comet together, losing that ice means losing the infrastructure of the comet itself. It can break apart into smaller chunks, like other comets have in the past.

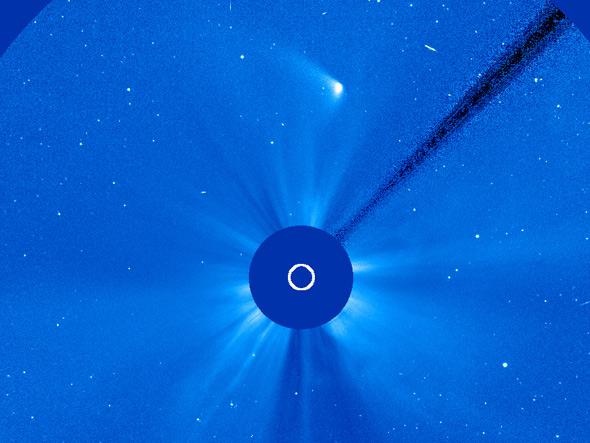

Photo by NASA / ESA / SOHO / Helioviewer.org

Still, it looked solid enough as it kept heading for the Sun… for a while. But a few hours later (but still before closest approach) it had faded considerably, and images from the NASA/ESA spacecraft SOHO showed it looking more smeared out. The trail of stuff narrowed toward the tip, but we didn’t see a single, bright spot there, which is what we expected for an intact comet. Those of us who were punditing at the time were, understandably, becoming convinced ISON was breaking up.

Pining for the Fjords

Then it got too close to the Sun for SOHO to see it (SOHO uses an occulting mask, a disk of metal, to block the fierce light of the Sun and allow it to see the fainter environment around our star; that’s why you see a black spot in the images, and the long bar to the upper right which holds the disk in place). We waited.

And waited.

At some point after perihelion I made a decision. I drew a line in the sand, saying I thought this was an ex-comet. But then, not long after, like Lazarus or a zombie, ISON came back from the dead.

But Wait! What Light Through Yonder SOHO Breaks?

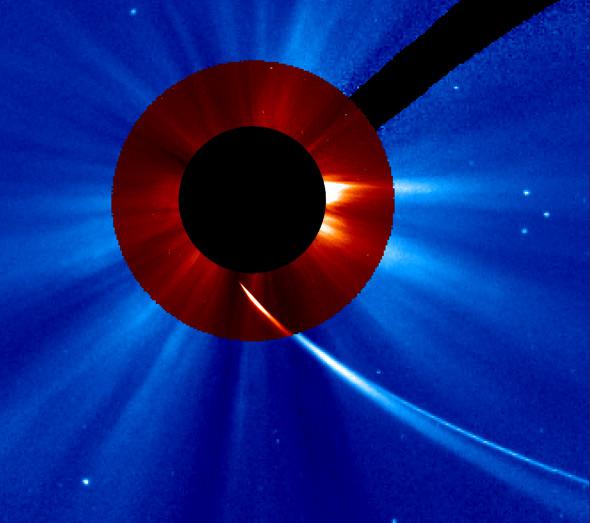

By 19:48 UTC, a little tadpole was visible in the inner SOHO images. Within a few hours it was clear something had made it around the Sun. But was it an intact comet, or just a dust cloud of debris ripped apart by the terrible forces it experienced?

Photo by NASA / ESA / SOHO / Helioviewer.org

That brings us to now. What of the comet? Well…we’re not really sure. The latest pictures do show a condensed blob of something, and it doesn’t look quite as much like a debris cloud as it did.

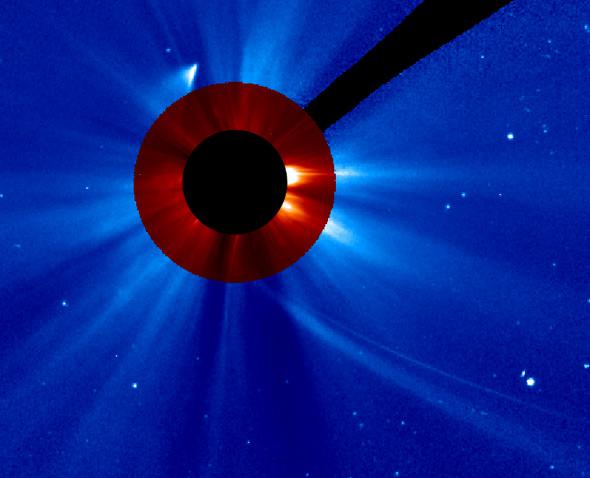

Best guess: As it rounded the Sun the solid nucleus fell apart. It may have released a lot of junk — dust, gas, whatever — but a sizeable chunk remained. That itself is still being heated by the Sun, and so is surrounded by a fuzzy coma of material. We can clearly see a tail of dust following behind it in the same orbit, and another tail of fine dust getting blown out by the solar wind (multiple tails of different compositions are common in comets).

So I wouldn’t say the comet survived, so much as some of it wasn’t destroyed. A subtle difference, perhaps, but clearly something is still there.

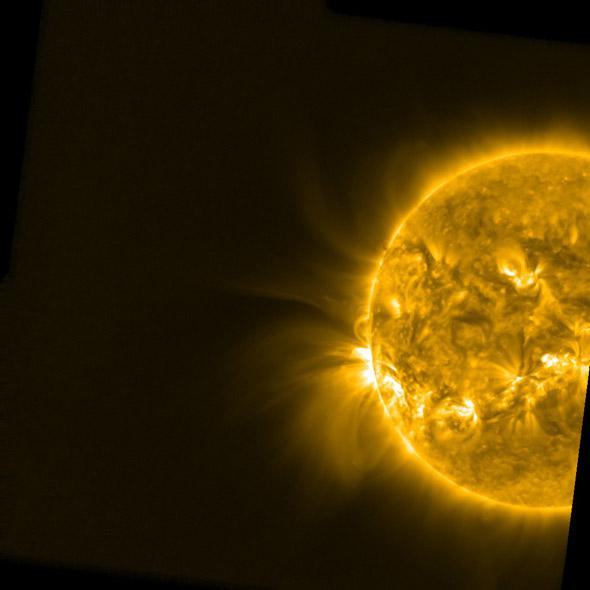

Photo by ESA / PROBA2

Interestingly, both the Solar Dynamics Observatory and the European PROBA2 spacecraft did not see any hint of ISON as it passed the Sun. That’s extremely puzzling; PROBA2 has a very sensitive camera. Both are easily able to detect oxygen atoms released by the comet, which should glow in ultraviolet light (and the oxygen would come from water, an abundant substance in the comet). It’s not clear at all why the comet was invisible; it may be more evidence it did mostly break up. But again, we’re still seeing a tail (which means it’s blowing out material), so the only thing we can be sure of is that there’s more to this story than we’ve figured out in this short time.

What’s Next?

I’ll note the trajectory of the comet hasn’t changed. Gravity is far and away the dominant force steering the comet, and it’s still on its way out. It’s still bright, though not nearly as bright as it was. And it’s still very close to the Sun, just a few degrees away, so it won’t be visible just yet.

However, after a few days, if it stays bright, it may be visible in the pre-dawn sky. I wouldn’t bet on it, but geez, I wouldn’t bet against it either with this comet. Look low to the eastern horizon while the sky is still dark; you may need binoculars. As far as I can tell, the tail (if any) will stick more or less straight up away from the horizon (depending on your latitude). It may be visible after sunset in the west-northwest as well, but the angle of the tail won’t be as good.

I do NOT suggest trying to see it while it’s still near the Sun; it’s too faint and the chance of eye damage (if you use optical aids like binoculars or a telescope) is too high to risk it.

My advice is to wait a few days to see if it’s visible to the eye before dawn, and in the meantime delight and be puzzled by the fantastic images we’re getting from space.

The comet, or what’s left of it, will make its closest approach to Earth at the end of December, when it will be 60 million kilometers away. A few weeks later, it’s possible that we’ll pass through the debris trail from ISON, and see some meteors from it. At this point, given the capricious nature of the comet, I’d score this one as a firm maybe. We’ll know more in the coming weeks. I don’t think there’s any real danger from big pieces, since the comet itself will be millions of kilometers away at the time, so don’t fret. We should be safe from needing Bruce Willis’s help here.

Ad Infinitum

This comet has been a weirdo since Day 1, and continues to surprise and fascinate astronomers. And normal people, too. I was overwhelmed with the response I got yesterday both during and after the NASA video Hangout, as well as on Twitter, where I was trying to keep up with this iceball as it performed its merry pranks for the planet to see. My tweets got hundreds of replies, in many different languages, showing how this event touched people all over our own small world.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: Comets and cats are equally predictable. It’s a losing game to be firm with them; your best move is to watch, wait, and enjoy the show while it happens. That’s my plan, for sure.

Tip o’ the Whipple Shield to my pal Craig DeForest for the PROBA2 news.