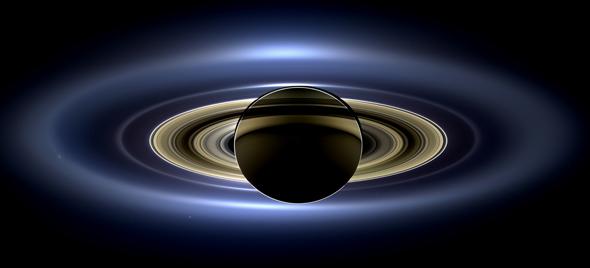

On July 19, 2013, the Cassini spacecraft was 1.2 million kilometers (750,000 miles) from Saturn, far enough that it was afforded a magnificent overview of the planet and its rings. Over a four-hour period it took a series of photos, one after another, panning and tilting across the ringed jewel of the solar system. It took scientists several months to carefully assemble them into a mosaic, preserving all the details both faint and bright.

What they created was worth the wait. Behold! Saturn!

Photo by NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

You absolutely 100% must see it in its full 9000 x 3500 pixel glory; shrinking it to fit the width of this blog is almost an insult to the nature of this picture.

There is so much to see here! The CiCLOPS site has a lengthy description (and there’s also a nicely annotated picture provided, too) but there are a few wonders I want to show you specifically.

Midnight View

First, the images were taken when Cassini was behind Saturn, if you will, on the side opposite the Sun. So from its viewpoint, Cassini saw the planet itself blocking the Sun. If you like, you can think of it as the spacecraft being over the night side of Saturn. But it wasn’t exactly centered: It was about 17° below (south) of the plane of the rings. If it had been exactly in the plane, the rings would be knife-edge thin, but instead, from that shallow angle, they cut across the image, perspective distorting them into flat ellipses.

Photo by NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

Saturn appears dark on its night side, except for a bright thin rim around its edge, which is scattered sunlight from the daylight side — the same sort of effect that makes dust motes glow when suspended in a sunbeam.

There is also an arcing band of light across Saturn, which is illumination from the rings themselves! They are bright and in full sunlight, so if you were on the dark side of Saturn the rings would be brilliant in the sky. That light softly illuminates the cloud tops of the planet. I call it ringshine, after Earthshine, when you can see the dark part of our own Moon due to the Earth reflecting sunlight there.

Also, in the picture the rings themselves cut across the planet’s disk, seen in silhouette where they are dark, but blocking the ringlit clouds below them. Note too the shadow of Saturn cutting narrowly across the rings to the upper right of the disk of the planet.

The rings dominate the picture, of course, the thousands of individual bands in the main rings seen backlit by our Sun. The main rings are bounded by the narrow, bright F ring. Outside that is the narrow fuzzy G ring, and then finally the broad, diffuse E ring. The rings appear brightest at the 12 and 6 o’clock positions due to backscatter, the icy particles sending the sunlight back toward Cassini, amplifying their brilliance.

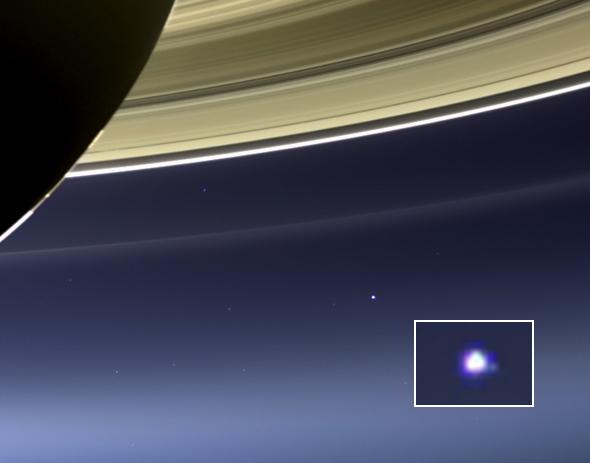

A Glance Toward Home

Because Cassini was pointed toward the Sun for these pictures, it is looking toward the inner solar system… which is also the direction to Earth. And we are there, just below and to the right of the planet’s dark silhouette.

Photo by NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

From that distant point, the Earth and Moon are barely separable by Cassini’s camera (I added a zoom of the Earth and Moon inset into the wider view). A shot made using the narrow-angle camera at the time shows them better. But I rather like this one; it gives you a real sense of just how terribly remote Saturn is from Earth. At the time, it was 1.4 billion (900 million) kilometers away.

Mind you: You’re in that picture. Every human alive at the time is captured inside the fuzzy blob; even the astronauts on board the International Space Station are well within the glowing pixels of our home planet seen here. That’s why JPL organized the Wave at Saturn campaign, and Carolyn Porco, imaging team leader for Cassini, also organized another called The Day The Earth Smiled. If Cassini was looking at us, why not look back?

I’ll note Venus and Mars are also in the huge Saturn mosaic. It really was a family portrait.

Plumes With a View

Photo by NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

There’s just so much to look at in this image, but there’s one more thing I want to point out in particular. While scanning the massive shot, I saw a very peculiar sight, but one I recognized right away. Seen here, it’s Saturn’s moon Enceladus. I knew what it was on sight because even from this distance you can see the geysers of liquid water erupting from the moon’s south pole!

This view of Enceladus is truly incredible. We’re seeing the dark side, but it looks half-lit because of light reflected from Saturn. It’s embedded in the diffuse E ring, which itself is created by the geysers on the moon, blasting tiny particles of ice into space, which then circle Saturn on their own (though some do rain down onto Saturn). The ring is very tenuous, but still substantial enough that you can actually see the shadow of Enceladus stretching off to the left, cast across the countless grains of ice!

Ad Infinitum

I could go on and on: There are stars in the background, which is very unusual in a picture of bright Saturn; more moons; more rings (I was unaware of the Pallene ring, the faint arc at 12 o’clock just inside the E ring; created by ice blasted off the tiny moon Pallene by impacts, it was discovered by Cassini just a few years ago)… just more to see everywhere you look.

And isn’t that the best part of all? There’s always more to see. We’ve been exploring the heavens for all of history, but we’ve only actually been able to get out there and poke around for a scant half-century or so. And look what we’ve found! Glories beyond counting, treasures to envelope our minds, sights of profound artistry.

And it never ends. There will always be more to find, more to explore, and more to learn. And it’s science that will take us there, propelled by our own imagination, our sense of wonder, and our desire to find things out.

[Correction (Nov. 14 at 04:00 UTC): I originally wrote that Enceladus was at an angle to the Sun that made it half-lit, but then saw my friend Emily Lakdawalla’s great video tour of this Saturn photo explaining that it was actually lit by Saturnlight.]