When you go outside at night and gaze upon the sky, it seems eternal and unchanging.

But that’s our own human limitation coloring our minds. We live on a much shorter time scale than the stars. But we’ve studied them, learned about them, and now have a great deal of understanding of them. Stars are much like us, in fact: They are born, they live for an amount of time, and they die. Some fade away, some explode, but in the end, like us, they are mortal.

That’s a modern realization. And it’s spawned a modern fable, too, which I have seen here and there, usually propagated through social media. Told as a morality tale, to give us a sense of perspective, it states this:

When looking at stars, you’re actually looking into the past. Many of the stars we see at night have already died.

I saw this most recently on the Twitter feed for ÜberFacts, which, apparently, sometimes posts incorrect (and commonly unsourced) “facts.” This is one of them.

It’s actually not too hard to understand. The first statement is actually correct; when you look at the stars you are seeing them as they once were. Light travels rapidly—as far as we know, it’s the fastest thing in the Universe—but it’s not infinitely fast. At 300,000 kilometers per second (186,000 miles per second), it takes light more than eight minutes to get from the closest star to Earth; you can think of it as seeing the Sun as it was eight minutes ago. The nearest known star to the Sun is the Alpha Centauri triple-star system, and light takes more than four years to get from there to here.

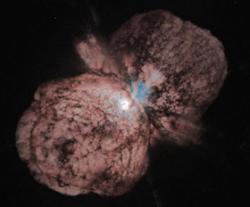

There are about 6,000 or so stars that are visible with the naked eye, and the vast majority of them are within about 1,000 light-years of the Sun. Stars dim quickly with distance; from even 60 light-years away, the Sun would fade to invisibility. Only the most luminous of stars can be seen from greater distance, stars like Deneb (probably 1,500–2,500 light-years away), Eta Carinae (7,500 light-years), and Rho Cassiopeiae (8,000–12,000 light-years). About a couple of dozen in total make that list.

So when you look up at the night you are seeing even the most distant stars in the sky as they were less than 10 millennia ago. Most are closer.

But stars live much, much longer than that. The Sun will continue on as it is now for many billions of years. Even the most luminous stars, which use up their core fuel far more quickly, can live for 1 million years or more. That means the odds of a star happening to die while its light is already on its way to Earth are very small; in terms of the star’s lifetime, a few thousand years is the blink of an eye. A star would have to be very, very near its own death for this to happen after a very, very long life.

I can think of very few exceptions, though Eta Carinae fits the bill. It’s on the edge of exploding; in the 1840s it underwent a massive paroxysm that was just short of a supernova event. It may not go off for another 50,000 years, but it might tonight. And at a distance of less than 10,000 light-years, those are not terrible odds that, in a sense, it’s already gone and we just don’t know it yet.

But that’s the exception, with the vast majority of stars still merrily fusing away, lighting up the galaxy.

I’d wager this aphorism about stars being already dead is wrong even with a decent telescope; the Milky Way is 100,000 light-years across, and only a few stars in it have a shorter lifespan than that. On average, very roughly, only two or three stars are expected to go supernova in the galaxy per century, so the light from a few thousand of such explosions is already on its way here. That may sound like a lot, but the Milky Way has something like 200 billion stars in it. So really, the number already dead but still shining in our sky is very small*.

Also, not every star explodes. Some swell into red giants, blow away their outer layers, and then fade away. That process, though, takes tens of millions of years to complete at least—again, far longer than the time it takes light to reach us.

Lower-mass stars don’t even do this. They just fade over time, lasting hundreds of billions of years. Most of those tiny cool red dwarfs will be around a long, long time. But for this they don’t even matter: Because they are so intrinsically dim, not a single red dwarf is visible to the naked eye—even the closest one, Proxima Centauri, is far too faint to see without a telescope.

No matter how you look at it, the idea that all, or even most, or even a lot, of the stars you can see in the sky are already dead is simply wrong. It sounds true, and kinda sorta fits with things you might think you know, but in the end the facts will win.

So when you look at the sky, feel confident in the fact that the stars you see are still there and will be for some time.

Dave Brosha, used by permission

*I’ll note that other galaxies are millions or even billions of light-years away, so the odds go up that many of the stars we see in them are already dead. But it takes a powerful telescope to see individual stars in a distant galaxy, so in my opinion this doesn’t count either way toward the aphorism.