Now that comet Pan-STARRS has started to move on after a showy appearance in the twilight skies, it’s time to turn our attention to the next comet that could turn out to be a show-stopper: C/2012 S1 (ISON), generally just called ISON.

The comet was discovered in September 2012 by the Russian observatory called International Scientific Optical Network—ISON—using only a 40 centimeter (16”) telescope. Like most comets, it’s a chunk of ice and rock a few kilometers across. As it nears the Sun the ice will turn directly into a gas, and it will shed dust to form a tail. As the dust and gas around it expand and reflect sunlight, the comet will get brighter, though exactly how bright is hard to say.

The basic stuff you want to know is this:

- Its orbit is nearly a perfect parabola, meaning this is probably its first ever pass into the inner solar system.

- It’s a Sun-grazer, meaning it’ll dip really close to the Sun before heading back out again.

- It’s been pretty active, blowing out lots of material despite being over 700 million kilometers from the Sun.

- That means it may get much brighter as it gets closer, and some estimates put it as easily outshining Venus! But it’s hard to predict.

- We are in no danger from this comet, which never gets closer than about 60 million kilometers from Earth, but we may pass through its debris early next year, sparking a cool meteor shower.

So here’s the scoop.

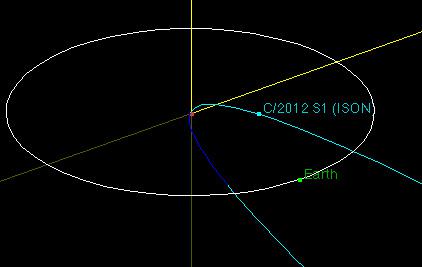

Its orbit is nearly a perfect parabola, meaning this is probably its first ever pass into the inner solar system.

Objects orbit the Sun in different kinds of paths. A closed path like a circle or ellipse means the object will orbit the Sun essentially forever—think planet or asteroid. Comets, though, tend to have very elongated orbits. There are probably trillions of icy chunks orbiting the Sun way out past Neptune, hundreds of billions of kilometers out. They spend vast amounts of time out there, and sometimes, slooowwwlllllyyyy start to drop toward the Sun, speeding up as they fall in.

NASA created this nifty animation of the orbit of ISON, seen from different angles:

Comet orbits typically are incredibly elongated ellipses, so long they start to look more like parabolae. Mathematically, a parabola is what you get if the comet drops literally from infinity, but starting a couple of hundred billion kilometers out is close enough. ISON may in fact have an even more extreme type of orbit called hyperbolic, which means it may have gotten a bit of an extra kick from a planet like Jupiter, giving it a scosh more energy. If this is the case, it will pass through the inner solar system with so much velocity it will never come back. Ever. It’ll travel out into interstellar space, and wander the galaxy.

So that’s pretty cool. This also means the comet is a virgin, so to speak. That makes it more interesting, astronomically: Every time a comet gets near the Sun it dies a little bit, losing gas and dust to space. If this is ISON’s first pass, that means it has a full quiver of material to shed, so it could be pretty bright.

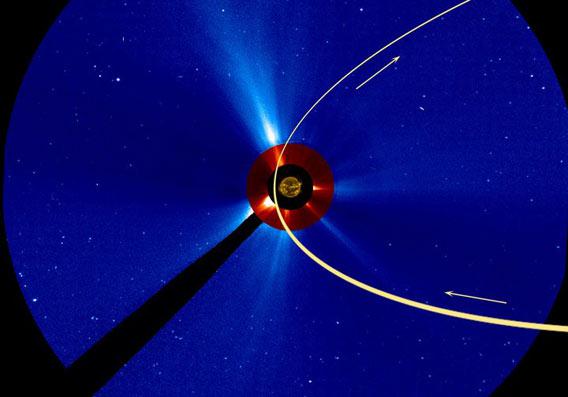

It’s a Sun-grazer, meaning it’ll dip really close to the Sun before heading back out again.

Image credit: NASA/SOHO

Not only that, on Nov. 28, when it reaches perihelion (its closest point to the Sun) it’ll practically skim the star’s surface at a distance of only 1.2 million km (700,000 miles), about three times the distance of the Moon from the Earth, for comparison. That’s amazingly close! From that distance the Sun will be nearly 100 times bigger than we see it from the Earth. For the comet, it’ll be like sticking its head in a 5000 degree oven.

It’ll probably survive—the close encounter will last a few days, not long enough to totally vaporize the comet—and at closest approach will be traveling at something like 600 kilometers per second. That’s well over a million miles per hour. If that doesn’t hurt your brain, think of it this way: That’s 0.2 percent the speed of light. Yowza.

For a brief time, that close to the Sun, it’ll blaze brightly, reflecting that dazzling light. But it doesn’t have to be close to be bright…

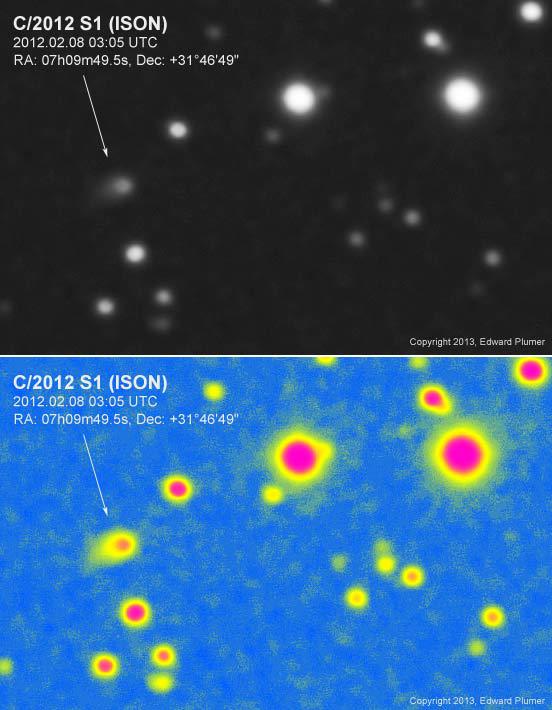

It’s been pretty active, blowing out lots of material despite being over 700 million kilometers from the Sun.

Image credit: NASA/Swift/D. Bodewits, UMCP

In January of 2013 NASA’s Swift satellite used its Ultraviolet and Optical Telescope (UVOT) to take a look at ISON. Frozen water in the comet is already turning into gas due to sunlight, and when it gets hit by solar UV the water breaks down into atomic hydrogen and hydroxyl (OH)*. Hydroxyl itself will then emit UV light, which Swift can see and use to estimate the amount of water in the comet.

Observations indicate that the comet is shedding about one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of water every second! That may sound like a lot, but a comet can have a lot of water. Estimates give the size of the comet as about three kilometers across, a bit smallish, but it still could have trillions of kilos of water inside. It’s good for a while.

It’s also blowing out a lot of dust, far more than water: about a ton per second. Mind you, at the time Swift was looking the comet was farther from the Sun than Jupiter! It’s cold out there, so the fact the comet is doing this at all is hinting at a pretty dynamic time coming soon.

That means it may get much brighter as it gets closer, and some estimates put it as easily outshining Venus! But it’s hard to predict.

Predicting how bright a comet will get is really hard. Sometimes they fizzle. That can happen if it slows blowing out material, for example. Comet Kohoutek in the 1970s is the poster child for this, never getting as bright as hoped.

ISON will get very close to the Sun, so it will certainly get bright then, but it’ll be so close it’ll be hard to see. In 2007 I saw comet McNaught at noon! But it was so close to the Sun it was really hard to do. Maybe we’ll get lucky this time, and ISON will do well. I’ve seen estimates that actually predict it could get as bright as the full Moon, but again you have to take those with a pretty good dose of NaCl.

One way or another it should start getting easy to see in small telescopes over the summer, and hopefully be naked-eye visible by fall.

We are in no danger from this comet, which never gets closer than about 60 million kilometers from Earth, but we may pass through its debris early next year, sparking a cool meteor shower.

Image credit: NASA/JPL

It bugs me to have to say it, but given the fear-mongering I see all the time online, it behooves me to say clearly that this comet poses no threat to Earth. It never gets very close to us, and its orbit is nearly perpendicular to ours.

However, the Earth will pass through the path of the comet a few weeks after the comet goes by, and since it’s shedding material we may get plow through some debris. This happens all the time with comets, and we call those events meteor showers. Given this comet is new, we may get a nice shower. Or, we very simply may not. Time will tell.

Interestingly, Mars will get a closer pass from ISON. On Oct. 1, 2013, the comet will pass roughly 10 million km (six million miles) from Mars. That’s far enough that the gravity of the planet won’t do much, and still pretty much guarantees Mars won’t see any impacts from the debris cloud.

But it’ll be a nice warm-up for 2014, when the comet C/2013 A1 (Siding Springs) will pass a few tens of thousands of kilometers from the planet! I suspect JPL engineers will use the near pass of ISON to test systems on the spaceprobes orbiting (and on) Mars now, getting observations of ISON as it blows past. That will help them understand better what to do when Siding Springs passes. I still wonder just how close that comet will get, and whether our probes are in any danger…

Image credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Axel Mellinger

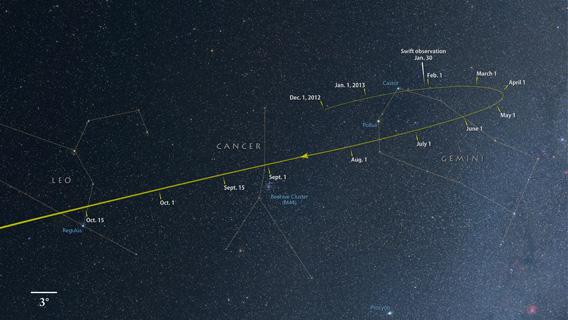

I’ll note that ISON has a weirdish orbit, coming in from north of the Earth’s orbital plane, dipping briefly south, then popping back up north. That means those of us above the equator will have a pretty good view. I expect we’ll be getting lots of amazing pictures of it, and I’m hoping to be one of the folks taking them.

But that’s months from now. I just wanted to give you a heads-up now, since you’ll be hearing a lot more about this celestial visitor in the months to come. As time goes on I’ll have more info, including more detailed star charts so you can see it yourself (like the one above), and instructions on how to safely view it (I add the adverb since it will be brightest when it’s close to the Sun, so observing has to be done with care).

So stay tuned. There may be lots more to come(t).

Correction (Apr. 3, 2013): I had mistakenly written this as “hydroxyl molecule (OH-)”, but the OH in this case does not have a negative charge.