Friday is the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 1 fire that killed three astronauts. I wrote the following article a few years ago, but my feelings have not changed at all. Space calls to us, and we must answer, even when we know we will lose people along the way. We can minimize this loss, but we cannot eradicate it. If you ask any astronaut, I expect they would agree.

Today marks the second in a week of three tragic anniversaries in space exploration. On Jan. 27, 1967, we lost three astronauts in the Apollo 1 fire. On Feb. 1, 2003, seven astronauts died when Columbia broke apart upon re-entering Earth’s atmosphere. And Jan. 28, 1986, is when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded, killing all seven astronauts on board.

All three of these events were horrible. All three were the results of unlikely chains of events that seemed inevitable afterward. All three sparked immense debate over the dangers and value of exploring space.

And all three should show us how important it is that we carry on that exploration.

There are two ways to look at why slipping loose the surly bonds of Earth is so critical. One is practical. Going into space has given us tremendous advantages in life. Global communication. Weather forecasting. Technology spinoffs that have generated vast economies. The list goes on and on. How many dangerous regimes have collapsed because we can directly see and talk to those being oppressed? How many lives have been saved by advance knowledge of crippling weather events? How much have our lives improved due to the wonderful technology generated? The money spent on space exploration has literally paid us back manifold.

That argument alone is more than enough to support both automated and crewed space exploration. But there’s more.

We are a species of explorers. It’s in our blood, in our makeup. We crave to see what’s around the next corner, what’s over that hill, what’s next in our adventure. Sometimes we learn something massively important, and sometimes we don’t. Sometimes we come home to tell the tale, and sometimes we don’t. Exploration has fantastic rewards, and grave dangers. But fulfilling our need to explore is its own goal.

The practical benefits of exploration are our sustenance, but the adventure itself is the flavor. The price we pay for this, sometimes, is counted in human lives. And it’s a terrible price. But we must continue to explore because it’s a part of us.

The very fact that so many people are so deeply affected by these events shows just how profoundly space exploration reaches into us. Any event involving large multiple deaths in a single, searing moment is going to resonate with us, and certainly watching it live on television will magnify that feeling. But in this case, we hold astronauts to a higher level. Like with any dangerous occupation that makes life better for others, risking their lives is part of the job requirement.

At first, it feels like this makes these losses cut even more. But it’s ironic: The astronauts themselves knew the risks and downplayed the significance of them potentially being killed. They thought it was worth the risk, or else they wouldn’t have done what they did. That doesn’t make their loss any easier, but it shows us that we must carry on—who could convey that message better than the ones who themselves sit on top of those rockets?

There are many reasons we lose lives exploring space. It’s inherently difficult and dangerous, a hostile environment that takes supreme and envelope-pushing effort even to reach. And there will always be human errors, those caused by carelessness, rush, politics, greed, and simple mistakes. We can minimize these risks in many ways, but over time, the odds of these mistakes leading to tragedy become inevitable.

The only way to absolutely minimize these risks is to stop exploring. And that’s unacceptable. Ships are safe in the harbor, but that’s not what ships are for.

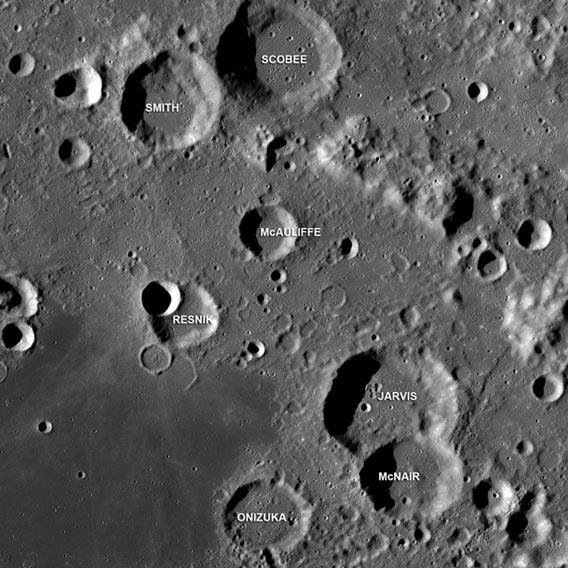

So, for Grissom, Chaffee, and White; for Scobee, Smith, McAuliffe, Onizuka, Resnick, McNair, and Jarvis; for Brown, Husband, Clark, Chawla, Anderson, McCool, and Ramon, and for all the others who gave their lives for this great adventure:

I hope that we have learned from your experience, I hope that we have become better through your experience, and that, while we will never forget what happened to you, we will also remember what you were trying to do, and what you did do.

Per ardua ad astra.

Some parts of this post are based on articles I have written in the past about these events.