One of the most exciting fields in astronomy—really, in all of science—is the search for alien worlds. The first planet around another star was found in 1992 (though the star was the remnant of a supernova, so not terribly Sun-like), and the first planet around a Sun-like star just three years later. Fast forward two decades, and we now know of hundreds of such planets, and have thousands more detected that have to be confirmed (the data look good, but we still call them candidates until confirmation).

In fact, there are enough that the field of exoplanets is in the next step of the scientific process past discovery: categorization. We have enough known planets orbiting other stars that we can start to plop different labels on them: massive, big, small, orbiting hot stars, orbiting cool ones, having tight orbits or wide-sweeping ones. And once you can do that some very, very interesting things start to fall in place.

For example, you can use some statistics to extrapolate how many planets there must be in our galaxy. A new study has done just that, and the number they get is stunning: they calculate there may be a hundred billion planets in the Milky Way, with 17 billion of them the size of Earth!

First, let me point out that previous studies have gotten roughly the same numbers (for example, recently my pal John Johnson of Caltech was part of an announcement that the number of planets in the Milky Way was around a hundred billion, using one star and its system of five planets as a basis; it’s solid work). This new study is important because it uses more data and analyzes it more robustly than most previous work.

Image credit: ESO/L. Calçada

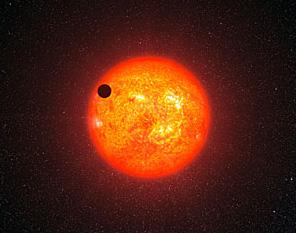

Here’s how it works: In 2009, NASA launched the Kepler spacecraft, tasked with finding exoplanets. It stares at one spot in the sky, peering at 150,000 stars. If a planet orbits a star, and the orbit lines up just right, then once per orbit the planet passes directly between us and the star—an event called a transit—dimming the starlight a bit. We can’t see the star’s disk or the planet directly, but that periodic dip in light can be used to determine the planet’s orbit and its size (the bigger the planet, the more it blocks the starlight). Well over a thousand new planet candidates have been found this way.

The astronomers in the new research looked at over 5000 potential periodic transit-like events. Comparing them to known issues with other events that can mimic transits (like binary stars, starspots, and more) and even things that can happen inside the telescope and camera that can look make stars dim and brighten, they found well over a thousand new planet candidates (1091, to be exact), bringing the total number of candidates to over 2000.

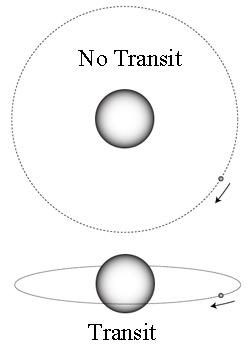

Adapted from a diagram by Greg Loughlin.

Since the orbit of the planet has to align in just the right way for us to see a transit (if the orbit is face-on, for example, we never see the planet block the star), it’s possible to extrapolate and determine how many planets we might miss out of the 100,000 stars observed. Since we know there are roughly 200 billion stars in the galaxy, we can then further extrapolate to calculate how many planets exist. Statistically determined, their result yields a hundred billion planets. We also know that the conditions under which planets form make it likely that most systems have more than one per star, so it’s like that tens of billions of alien solar systems are scattered throughout the Milky Way.

That is, simply put, one of the most poetic and exciting scenarios I can imagine in science.

And it gets better. Because so many planets are found, and we can measure their sizes, we can extrapolate that as well. What the astronomers found is that 17% of all planets are roughly the size of Earth, meaning there may be well over ten billion Earth-sized planets in the galaxy!

Mind you, this doesn’t necessarily mean Earth-like. Most will be too hot for life, since they’ll be close in to their parent star. But you know what? I still like those odds.

What I found most interesting, though, is that they found that these terrestrial planets aren’t picky about star hosts. They found just as many, percentage-wise, around dinky low mass stars as ones like the Sun. This means conditions to create these planets are common when stars are born, and Earths are relatively easy to make. That sounds good to me, too. Maybe Gene Roddenberry had it right all along…

When I was a kid, there were nine planets (or eight, take your pick). We had no proof, zero, of any other star in the Universe with planets. Now we know of over a thousand, and there are billions upon billions more waiting to be found. And all of this came about because someone was curious, wanting to know if maybe, just maybe we could spot one.

Other things may lay claim to the ability, but science is the best way we have to turn our dreams and imagination into reality. There are literally unknown worlds out there just waiting to be discovered, and because of science, we’ll find ‘em.