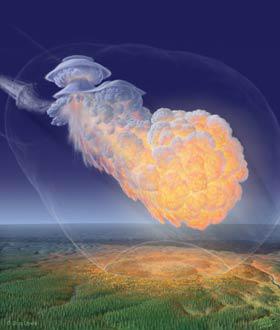

Over a century ago, on June 30, 1908, an unearthly visitor came to our planet. A chunk of rock (or possibly ice) about 30 meters across—the size of a house—barreled in at a speed probably 50 times that of a rifle bullet. Ramming through the Earth’s atmosphere, incredible forces compressed it, crumbled it, and when it reached a height of just a few kilometers above the ground, those forces won. In a matter of just a few seconds the energy of its immense speed was converted into heat, and it exploded.

This was the famed Tunguska event. The fireball created a huge forest fire over hundreds of square kilometers of the Podkamennaya Tunguska River region of the Siberian forest … but then the immense shock wave from the blast touched down. It blew the fire out and swept down those trees like a rolling pin, knocking down untold millions of them. It took 20 years to mount an expedition to the remote location, and I’ve often wondered exactly what the explorers saw when they got there.

I expect it was something that looked very much like this:

Image credit: Rod Benson. Used by permission.

Those aren’t toothpicks, those are trees, my friends, lodgepole pines, knocked down like so many twigs in 1999. This picture was taken by Rod Benson, and it shows trees in Montana felled by a microburst, a rare weather phenomenon that can create powerful winds, characterized by a huge and sudden downward rush of air from a thundercloud. The air accelerates down, then slams into the ground and spreads out at high speed, easily hitting 150 kph.

Here’s another view, also taken by Benson:

Image credit: Rod Benson. Used by permission.

I’ve seen quite a few extraordinary weather events, but something like this is terrifying. Incredibly, the power for these massive downward blasts comes from evaporation! Raindrops in a cloud can evaporate, which cools the surrounding air considerably (like sweat cools your skin). The colder air is denser and begins to sink. In some rare circumstances, that air can sink very rapidly, accelerated by various processes. A microburst can be many kilometers across and affect a huge region. There have been several airplane crashes caused by them, so they’re intensely scrutinized by meteorologists.

Image credit: Don Davis. Used by permssion.

And as huge and devastating as that is, it’s peanuts compared to what happened in Tunguska in 1908. The explosion of the interplanetary debris was equivalent to about a 15- to 20-megaton nuclear weapon—15 to 20 million tons of TNT detonating. The explosive yield of the blast was estimated in part by the size of the area with trees blown down. Incredibly, studying weather phenomena like microbursts helps us learn about even more extreme phenomena like asteroid impacts.

We don’t know how often such impacts happen, but on average it’s probably every few centuries. The odds of one happening on any given day are incredibly small, but over enough time, it’s inevitable. That’s why we need to be patrolling the skies even more earnestly, looking for these cosmic interlopers.

Tip o’ the bomb shelter door to the Earth Science Picture of the Day.