Over its long, long history, the Moon has been cosmically battered on an epic scale. Impacts from billions of asteroids and comets have left it battle-scarred, its history laid bare on its surface. Because it has no atmosphere, it has no erosion (except for the very slow wearing by the solar wind and the breakdown of rocks from “thermal cycling,” the large change in temperature between day and night). Its ancient craters are therefore in relatively pristine condition.

This is a scientific boon: It allows us to study craters that are incredibly old and sometimes even compare ones of very different ages and see how things change over time. Here is an excellent example:

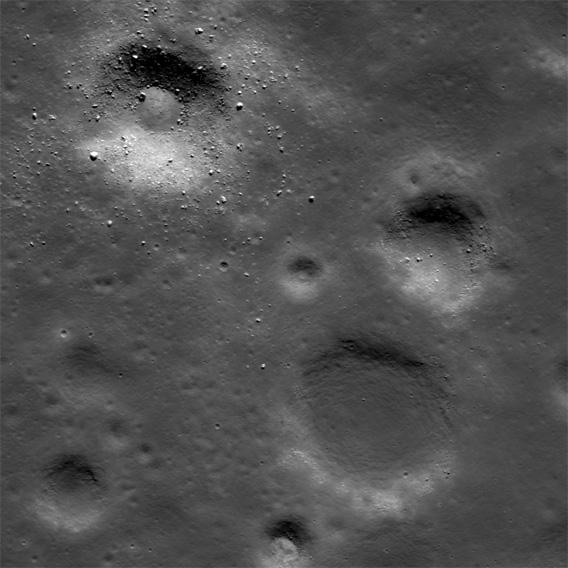

Image credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

This shot, taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, shows a relatively young crater carved into ancient geology. Most of the craters in the picture have a soft, eroded look to them; they are probably very old, and long after they formed were filled in a bit by some sort of local event like a nearby impact blasting out debris that rained down, or perhaps volcanism flooding them with lava. That tends to leave a flatter floor and eroded rims.

The new crater, to the upper left, is starkly different. The rim is more sharply-defined, the floor bowl-shaped, the ejected material fresh-looking and bright (solar wind darkens it with time, sometimes allowing age estimates to be made). You can see lots of boulders strewn around from its impact—some got thrown pretty far; the image is about 1.6 kilometers (one mile) across. In this case, at a glance it’s pretty clear which crater is the most recent.

Speaking of fresh craters, how old would you say this one is?

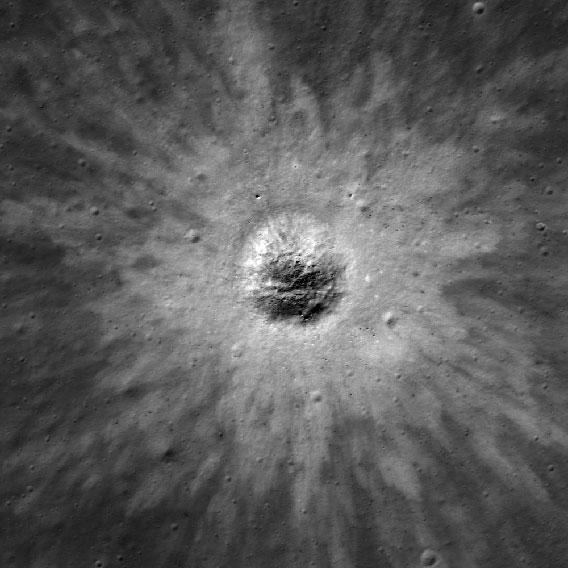

Image credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

This is also an LRO shot, showing a crater a little bit more than 300 meters across. Again, it has all the signs of being much younger than most other impacts on the Moon: sharp features, fresh rays extending outward, a few boulders here and there blasted out.

I was surprised then to read that this crater is probably about 800 million years old! That’s considered young. Timescales on the Moon are way different than on Earth.

And here’s another crater, roughly 240 meters wide, which is also relatively young but very odd looking:

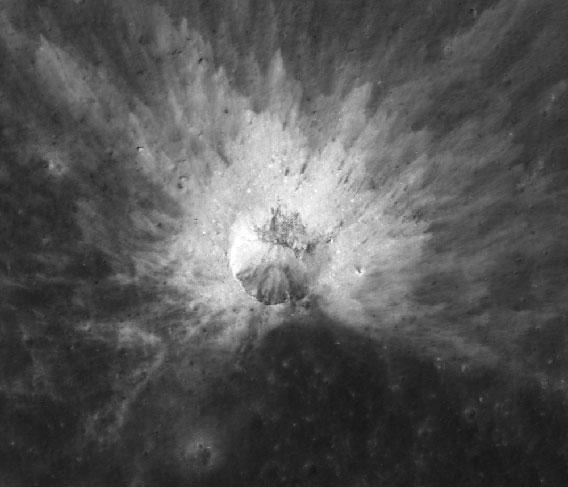

Image credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

As before, note how bright the pattern of ejected material is and how the other features are sharp and uneroded. But it’s weird. The ejecta seem to have been preferentially blasted to the north (up), and the interior of the crater itself isn’t symmetric, with a longer, gentler slope to the south and a shorter, steeper one to the north. What could cause that?

It turns out it was a glancing blow. In general, craters stay circular even when the rock isn’t coming in straight down; the explosion from the huge energy of impact still expands in a circle. You don’t start to see real differences until the impact angle is about 15 degrees or less from horizontal, a very shallow angle. At that point the direction of flight becomes important, and impact craters become more elongated and elliptical, and the material explosively excavated gets blasted forward, along the trajectory of the impactor instead of all around it.

This crater was formed when an asteroid hit with a glancing blow, at just such a low angle. And we can even tell it came in from the south, moving north! The rays coming out make that clear, since the majority of the stuff that splashed out is to the north.

It’s amazing, isn’t it, what you can see at a glance once you know what you’re looking for? Examining craters on the Moon gives scientists an excellent perspective on its history dating back several billion years, something far more difficult to do on Earth because of erosion and continental drift.

Heck, just counting craters in a region can help identify the age of the area compared to other lunar regions. That’s why CosmoQuest hosts the Moon Mappers citizen science project; you can count and measure the sizes of craters on the Moon, data which scientists can then use to make progress understanding our nearest cosmic neighbor. It’s real science, and you can help. It’s also fun!