Galaxies used to be called “island universes,” a poetic but not entirely inaccurate phrase. In general, each is a collection of billions of stars as well as huge clouds of gas and dust all held together by gravity (there’s also dark matter, too, but we don’t know much about that except that it’s there).

In the 1980s, we learned that every big galaxy has a huge black hole in its center. Our own Milky Way has one that has a mass 4 million times that of the Sun. That’s big for a black hole, but it’s a tiny fraction of the mass of the galaxy, which is about 400 billion times the Sun’s mass. In fact, our central black hole is a bit of a lightweight; the proportion of black hole mass compared to galaxy mass is usually about 0.1 percent, where ours is 0.01 percent.

A few years ago, astronomers discovered that there appears to be a relationship between the mass of the galaxy’s central black hole and the mass of the galaxy’s inner region, called the bulge. A bigger bulge means a bigger black hole. That ratio is interesting: In general, it holds true across a wide range of galaxies. For some reason, properties of the central black hole and the greater galaxy around it are tied together. That’s telling us something about how galaxies form and how they grow, if we can just figure out why they’re connected.

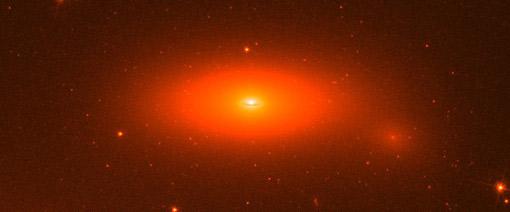

Of course, in every group, someone has to be a troublemaker. Meet NGC 1277, a disk-shaped galaxy about 250 million light years from Earth:

Image credit: NASA / ESA / Fabian / Remco C. E. van den Bosch (MPIA)

Astronomers studying this galaxy have determined that its central black hole is a whopper: It has a mass about 17 billion times the mass of the Sun! This may be a record; it’s certainly among the most massive black holes known. The problem is, that’s far more massive than the central bulge of NGC 1277 would suggest the black hole should be. It’s well over half the total mass of the bulge! In fact, the entire mass of the galaxy is about 120 billion solar masses, which means the black hole at its heart is 14 percent of the total galaxy’s mass; compare that to the Milky Way’s black hole mass of 0.01 percent and you’ll see why astronomers were shocked.

So that’s weird. How could that black hole have gotten that massive?

Galaxies form from huge collapsing clouds of gas. Looking at the early Universe, we see most galaxies are small and shapeless, but nowadays many are big, like the Milky Way. We think that they grow by eating each other! Yes, galactic cannibalism. Usually they collide and merge over time, and the two black holes from the two galaxies also merge, forming one bigger black hole. If that’s the case, then the mass of the black hole and the mass of the galaxy itself should grow at roughly the same rate, and be pretty much the same for every galaxy.

For some reason that didn’t happen with NGC 1277. The astronomers were conducting a survey of galaxies, looking at many of them and figuring out the galaxy bulge to black hole ratio. After examining 700 galaxies, they found five others with abnormally high ratios, though none as beefy as NGC 1277. This means there are exceptions to the rule; not many, but they exist. Interestingly, all of them appear to be compact galaxies, smaller than you might expect given their mass. That may be another useful clue… but what that might mean is still unknown.

Still, that’s OK! We’re seeing the tip of the iceberg here, so to speak, showing us that something is going on, and teasing us with what it might be. Scientists love a puzzle.

Image credit: David W. Hogg, Michael Blanton, and the SDSS Collaboration

And sometimes, it’s the exceptions that force us to examine the rules. We have several hypotheses about why the black holes and galaxies would have correlated masses, but we’re not sure which one is correct. We need outliers like NGC 1277 to shows us which ideas won’t work so that we can either modify them or throw them away and find ones that work better.

How did our Milky Way get to be so big? Why is our black hole so small? Why are others so big? Why is a black hole so terribly important in the structure of a galaxy that’s millions of times bigger? Answering those questions is the payoff we’re looking for, and knowledge is the reward when you gaze into the dark monster that lurks at the heart of every galaxy.