Today astronomers announced a new addition to a very exclusive club: an actual, direct picture of a planet orbiting another star!

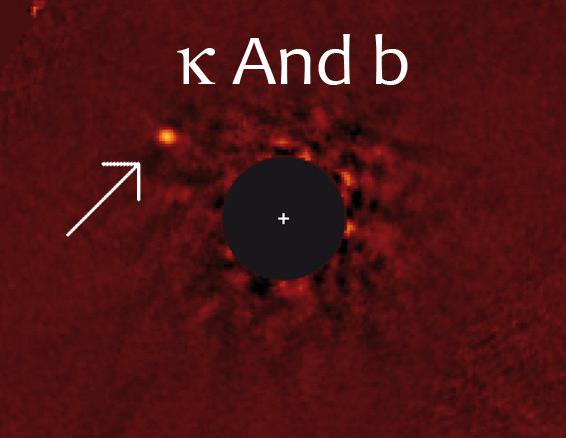

The newly discovered planet is called Kappa Andromedae b, or κ And b for short. I’ll tell you all about it, and why it’s so very interesting, but first, here’s the picture:

NAOJ / Subaru / J. Carson (College of Charleston) / T. Currie (University Toronto)

The star, κ And, is bright enough to see with the naked eye. It’s about 170 light years away, pretty close as these things go (a mere 1700 trillion kilometers; better pack a lunch if you plan to visit). It’s more than twice the mass of the Sun, much more luminous, and pretty young: about 30 million years old. Our Sun is 4.6 billion years old, for comparison. κ And is the most massive star yet seen to harbor a planet.

The astronomers used the Japanese Subaru telescope in Hawaii to specifically target nearby stars, hoping to see either planets or, more likely, disks of material surrounding the stars from which planets form. Those disks are easier to spot (they’re bigger and brighter) but finding a planet is a pretty awesome bonus.

κ And b, the planet, was first seen in images taken on Jan. 1, 2012—what a way to ring in the new year!—using a telescopic observing technique that makes most of the light from the star go away but leaves the planet’s light to get through. If you’re curious you can read about the method, so I won’t go into details. But I will say I used a similar technique to look for planets and disks around nearby stars back when I worked on Hubble, and it’s nice to see it working so well now.

More than 800 planets are known to orbit other stars, but the methods used to find the vast majority of them are indirect: We see their effect on their stars, but we don’t see the planets themselves. Using various methods, fewer than a dozen exoplanets have been actually spotted in pictures like this one with κ And b, so it’s a pretty elite membership. We’re on the verge of technology—space telescopes, better hardware on the ground, more clever software techniques—that will open the floodgates of finding these elusive and dim worlds, but for now each one we find is a precious jewel.

Image credit: ESO

I’ve set up a gallery of pictures showing all these worlds found so far. It’s an amazing thing to actually see those planets that orbit stars so many light years away. This is an incredible field of study right now.

The planet κ And b pops right out in the Subaru telescope picture, which is pretty amazing; typically a star is a billion times brighter than any planets orbiting it, so being able to see the planet so clearly is very nice. It helps that the planet orbits the star over 8 billion kilometers (5 billion miles) out, reducing the glare significantly. It also promises that more observations in the future will reveal a lot more information about it.

The current analysis indicates the planet is about 13 times the mass of Jupiter, and that made me raise my eyebrows. We don’t really have a good definition of what a “planet” is, but a star is something so massive it can fuse hydrogen into helium in its core—the pressure and temperature are so high in the star’s heart that it acts something like a controlled thermonuclear bomb.

But there exists a type of object called a brown dwarf that is midway between a planet and a star. It’s massive enough that for a time in its core it can fuse a particular flavor of hydrogen called deuterium, but after a while that turns off. Anything below that mass doesn’t have the oomph to get fusion started, and we call those objects planets. The upper mass limit before deuterium fusion starts? Thirteen times that of Jupiter, right where κ And b is.

So it’s possible that, by strict definition, κ And b isn’t a planet. However, the mass estimate for it depends on a lot of things: the age of the system, how bright it is, its temperature, what colors it has (literally, comparing how much light it gives off in the blue end of the spectrum versus red, and so on; that can tell an astronomer a lot about the object). These numbers are fed into computer models that then calculate the mass.

The age is most important, because while an old planet (like Earth) shines by reflecting light from its star, a young planet is still hot from its formation, and glows on its own, fading with time. It’s like a hot coal that shines white, then fades and turns redder with time. The more massive a young planet is, the brighter (and bluer) it is. For κ And b, one model gives a mass of 13 Jupiters, another gives it a lower mass of closer to 12. If the latter is correct, we have a true planet on our hands. Even if it’s more massive than that, other factors can come into play keeping it a planet by definition.

But either way this is pretty cool. For one thing, it tests our models to their limits, which is always good. We want better models! Finding test cases near the limits is a good way to figure out how to refine our understanding of the physics. And honestly, our definitions are a little arbitrary anyway. Don’t let some hard-and-fast interpretation keep you away from the sheer wonder of this discovery!

I can’t stress enough how exciting it is to watch astronomers get pictures like this! When I was a kid, the only planets we knew were in our own solar system. Heck, that was true even when I was in college and grad school. But then the first was found, and then a few more … and now we’re closing in on a thousand such worlds!

And even then we’re only skimming the thinnest of surfaces: Astronomers estimate that there are hundreds of billions of planets in our Milky Way alone—possibly even outnumbering all the stars in the galaxy!

Think on that the next time you gaze out into the night sky. Planets, maybe several, circle a large fraction of those stars. Only a few will be like our own home, but even then there could be billions of Earths out there. Billions.