What’s it like to fly through space, looking back at the Sun and planets as you leave them behind at multiple times the speed of light?

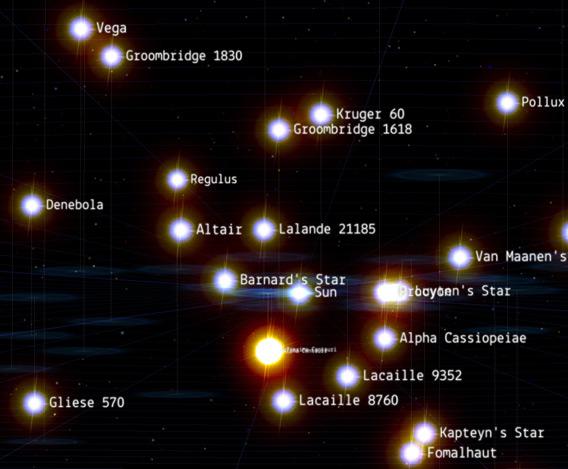

Probably something very much like what you can see playing with Google Chrome’s fun tool, 100,000 Stars:

Image credit: Google Chrome

This is a lovely browser-based app that plots the nearest 100,000 stars to the Sun in 3-D space. You can zoom in and out, fly around, and get more info on specific stars by clicking their names as they pop up. You can even zoom way out to see where our solar neighborhood is with respect to the rest of the Milky Way galaxy (though that part is not using actual data for visualization).

The interface is pretty smooth, and I found it works well on my Mac using either Chrome or Firefox. (NOTE FOR MAC GEEKS: in Safari it loaded a preset video and told me I needed WebGL for it to work. I followed the instructions on the WebGL page to implement it, but found it didn’t work on my iMac running OS 10.8.2. Maybe you’ll have better luck.) The app starts you off near the Sun, and you can zoom in and out using the vertical slider bar on the right. Soothing music plays while you do, which (nicely!) can be easily switched off if you prefer by clicking the speaker icon above the zoom bar.

At the upper left is a button that sets you on a nice guided tour, but don’t be afraid to just grab the conn and head out to the second star on the left; the interface for the app is fairly intuitive. You can click and drag to rotate the view, and my mouse wheel did fine for zooming (or you can use the slider bar).

It’s fun to fly around and zoom in on other stars. Once you do, you can click a link that displays the Wikipedia entry for the star. One fun thing is the graph icon next to the tour at the upper left that’s labeled “Toggle spectral index.” If you click it, all the stars are replaced by colored squares representing the stars’ colors—that’s what “spectral index” means in astronomy-talk. Pretty cool.

Having said that, I found it frustrating that once you zoom in on a star, it’s really difficult to center things back on the Sun. It would be nice if there were a “home” button (maybe the escape key) to bring you back to our home star. Also, a lot of the fainter stars aren’t labeled; as an example I couldn’t find Wolf 359, a nearby red dwarf made famous by Star Trek: The Next Generation as the location of the destruction of the Federation fleet by the Borg. At less than eight light years from Earth, it’s one of the closest stars, but it wasn’t labeled. Also, bizarrely, I couldn’t find Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky and only nine light years away! So the map needs a few tweaks, I think.

I don’t mean to harp on this, though. Mind you, this is an experiment! As a first shot, it’s very cool. I can think of lots of ways of making it even cooler, and I bet they’ll add fun features as time goes on.

Image credit: Google Chrome

And in fact, one thing I noticed can be a learning moment. If you zoom out, you see all the mapped stars surrounding the Sun in rough sphere. That’s an illusion! In reality, stars are distributed all throughout space around the Sun for hundreds of light years, well beyond the scale of this app.

So why the sphere? The folks at Google included all the stars listed in various astronomical catalogs, and in some cases those catalogs have a brightness limit. Stars that are too faint don’t get included. Like any other source of light, stars fade with distance, so as you back away from the Sun in any direction in the simulation, you see fewer stars. At some distance centered on the Sun, the catalogs stop listing stars, and that limit is roughly the surface of a sphere some distance out from home, depending on the type of star (some are brighter than others, so you can see them when they’re farther away). If the catalogs contained every single star in the galaxy, you wouldn’t see that at all. You’d just keep seeing more and more stars out to the edges of the galaxy itself.

This sort of thing is called a selection effect, an effect caused by the way you select what you see (in this case, visible stars). It’s not real, and if you want to understand what the Universe is really like, you have to try to understand all your selection effects and account for them. Otherwise, you might fool yourself into thinking something is real when it’s actually an illusion, a trick of the brain, just a limitation of the way we perceive the world.

That’s a pretty good thing to be aware of. The Universe isn’t trying to trick us, but our brains sure are. If everyone knew that, I bet a lot of nonsense in the world would evaporate overnight.

Anyway, I think you’ll enjoy playing around with 100,000 Stars, and I very much look forward to seeing what other developers can do with it. I imagine it would be useful to people creating games, or writers who want to have more sci in their sci-fi.

And? It’s fun for us too, just sitting at our desks playing Starship Captain. You never get too old for that.