In the race to find the weirdest planet orbiting another star, we may have a front runner: GJ 667Cc, a super-Earth orbiting one star in a triple system that’s actually relatively closeby. And oh yeah: it just so happens to be in just the right spot to be potentially inhabitable!

Of course, I have some caveats, so don’t get too excited. But this is a weird and pretty cool one!

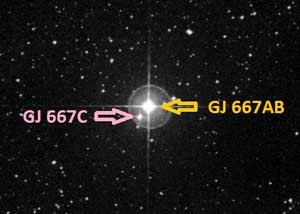

GJ 667 is a triple star system that’s right in our back yard as these things go: it’s only about 22 light years away, making it one of the closest star systems in the sky. It’s composed of two stars a bit smaller and cooler than the Sun which orbit each other closely, and a third, smaller star orbiting the pair about 35 billion km (20 billion miles) out. Stars in multiple systems get capital letters to distinguish them, so the two in the binary are GJ 667 A and B, and the third one is GJ 667C.

That third star is the interesting one. It’s a cool, red M dwarf with about a third the diameter of the Sun. Fainter, too: it only puts out about 1% of the light the Sun does. It’s been studied for years to look for planets around it, and while there have been some signs found, this new research is the first solid detection of planets that’s been published.

They used the Doppler method (sometimes called the Reflexive Velocity method): as planets orbit a star, their gravity tugs on it. We usually can’t see this motion directly, but a spectrum can reveal a Doppler shift, similar to the change in pitch you hear when a car or train goes by. If the spectrum has a high enough resolution, and the analysis very carefully done, there’s a lot you can tell by measuring it. You can get the planet’s mass, its period, and even the shape of its orbit.

In this case, the spectrum reveals GJ 667C may have four planets! Two very strong signals pop up with periods of 7 and 28 days, a third one at 75 days, and a possible trending shift in the spectrum that may point to a planet orbiting in a very roughly 20 year period.

In this case, the spectrum reveals GJ 667C may have four planets! Two very strong signals pop up with periods of 7 and 28 days, a third one at 75 days, and a possible trending shift in the spectrum that may point to a planet orbiting in a very roughly 20 year period.

It’s that second planet, GJ 667C with a 28 day orbit that’s so interesting. Its mass is at least 4.5 times that of the Earth, so it’s hefty. A 28 day orbit puts it pretty close to the parent star – about 7 million kilometers, or less than 5 million miles (Mercury is 57 million km from the Sun, by comparison). But remember, GJ 667C is a very dim bulb, so being that close means that the planet is actually right in the middle of the star’s habitable zone! The HZ is the distance where liquid water could exist on a planet – it depends on the size and temperature of a star, and also on the planet’s characteristics. A cloudy planet can hold heat better through the greenhouse effect, so it can be farther from the star and still be warm, for example. So this planet, if it’s rocky, might have liquid water! Of course, we know nothing about the planet itself except its mass, and even that’s a lower limit, due to the physics of how it’s measured based on the star’s spectrum. Still, we can use that number and play a bit. You might think that mass gives it a crushingly higher gravity than Earth. But wait!

The gravity you feel standing on the surface of a planet does depend on its mass – double the mass and you double the gravity – but it also depends on the inverse square of its size. So if you keep it the same mass but double the radius, the gravity drops by a factor of 4. So if GJ 667Cc has 4.5 times the Earth’s mass, but is twice as big, the gravity on the surface could be quite close to ours.

My point: don’t judge a planet by its mass until you know its girth.

Of course, we don’t know if this planet has an atmosphere or anything like that, either. It seems likely; it should have enough gravity to hold onto some gases. And if it does have an atmosphere, we don’t know if it has water or anything like that.

So there are a lot of unknowns here (which is why I warned you not to get too excited up front), but even so, there’s some reason to be hopeful. Why?

Two reasons. One is that these dinky red dwarf stars are by far the most numerous in the galaxy. They outnumber stars like the Sun by nearly 10 to 1. So if this one has a planet – and in a triple system! – then it’s likely that planets are extremely common in the galaxy. We’re getting that from lots of different studies, but it’s nice to see that fall into line here, too.

Second, remember, it’s close by (not that we’ll be heading there any time soon, but still). 20 light years is nothing compared to he 100,000 light year diameter of our galaxy. Just by random chance, having a planet even remotely Earthlike at that distance implies there are billions more in our galaxy alone!

Third, these stars are deficient in heavy elements. The spectrum of GJ 667C reveals it has far less things like oxygen and iron in it than the Sun does. Studies have shown that stars like this are less likely to have planets than stars like the Sun, which are rich in there elements. Maybe we got lucky that a nearby deficient star has planets, or maybe the earlier work is off a bit and stars like this do have planets. Either way, it again implies planets are extremely abundant in the galaxy.

So no matter how you look at it, this is good news. And it’s one step closer to the big goal of exoplanet astronomy: finding another Earth. That day is approaching. Maybe even soon.

Image credits: G. Anglada-Escudé using the program Celestia; G. Anglada-Escudé/DSS.

Related posts:

- Kepler confirms first planet found in the habitable zone of a Sun-like star!

- A tiny wobble reveals a massive planet

- How many habitable planets are there in the galaxy?

- New study: 1/3 of Sun-like stars might have terrestrial planets in their habitable zones