The Sun is literally a middle-aged star; approaching the midpoint between its birth over 4 billion years ago and its eventual death about 6 billion years from now. But the Sun is one of hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way galaxy, and we see them at all different ages, from their spastic births to their (in some cases) hyperspastic deaths. In many cases the way a star dies is foretold by how its born, so the study of star birth is a rich and fascinating field.

It’s also surpassingly beautiful, since stars are formed from the swirling chaos of thick clouds of gas and dust, lit up by the various newborns embedded within. You’ll find no finer example of this than the large nebula called Sharpless 2-239, a sprawling stellar nursery about 500 light years away in the direction of Taurus, and you may find no finer picture of it than this one taken by astronomer Adam Block using the 0.8 meter telescope at the Mt. Lemmon SkyCenter in Arizona:

[Click to ennebulenate, and yes, you want to.]

Isn’t that breathtaking? This image shows a portion of a much larger complex which currently has over a dozen stars forming inside it. Several of the stars you see here are quite young, only a few million years old. Since these are low mass stars like the Sun, and will merrily fuse hydrogen into helium for billions of years, this is like seeing a human baby when it’s less than a month old.

And, like babies will, these stars eject material from both ends: called bipolar outflow, twin beams of material (typically called “jets”) are screaming out of these newborns at several hundred kilometers per second in opposite directions. These jets slam into the dense surrounding material, compressing it, heating it up, and causing it to glow. The structure you see fanning out to the lower left is from one of these jets, the one headed more or less toward us. The one moving in the other direction is mostly hidden from our view by the thick dust in the region.

But there’s much much more going on here…

The red blob at the tip of apex of the fanned-out structure (just to the left and above the center) is the baby star causing all this commotion. It’s called IRS5, or sometimes HH154, and it’s the one emitting jets. The pink color you see in the picture is from warm hydrogen gas glowing due to this mechanism, and the other colors are coming from elements in the gas like oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur. As you can tell, the material farther out is quite dark, and in fact is so thick it absorbs the light from the stars inside; if they weren’t so active we wouldn’t see them at all!

The red blob at the tip of apex of the fanned-out structure (just to the left and above the center) is the baby star causing all this commotion. It’s called IRS5, or sometimes HH154, and it’s the one emitting jets. The pink color you see in the picture is from warm hydrogen gas glowing due to this mechanism, and the other colors are coming from elements in the gas like oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur. As you can tell, the material farther out is quite dark, and in fact is so thick it absorbs the light from the stars inside; if they weren’t so active we wouldn’t see them at all!

At least, not in visible light. When you look in other wavelengths, you see deeper into the dust. The image above, taken by the infrared 2MASS survey, shows the glow of the star and nebulosity just outside the eye’s range of color (I rotated the image and changed the scale to better match the image above). Light from deeper inside the cloud can be seen, and you can now see the young star lighting up the small wisp of gas above and to the right of IRS5 – a star that’s invisible in the first image.

Things get even more interesting if you use a big telescope with high-resolution to zoom in on the star in the infrared. Using the monster Subaru telescope in Japan, astronomers obtained this next image of IRS5, and you can clearly see the jet of material… except, wait a sec, there are two jets!

Things get even more interesting if you use a big telescope with high-resolution to zoom in on the star in the infrared. Using the monster Subaru telescope in Japan, astronomers obtained this next image of IRS5, and you can clearly see the jet of material… except, wait a sec, there are two jets!

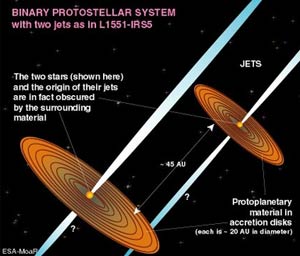

Yup. That’s because IRS5 is actually a binary star, two young stars orbiting each other. In fact many of the stars in Sh2-239 are binaries.

In the case of IRS5, the two stars are about 10 billion kilometers apart – bigger than the diameter of Neptune’s orbit. Each star is surrounded by a flat disk of material probably 3 billion kilometers across composed of leftover material from the formation of the stars; this material may even form planets in the coming eons.

Amazing, isn’t it? What appears to the eye at first as a formless blob actually takes on a interesting shape when you start to look more closely. And when you look differently, you see structure that yields more insight on the actual events going on: the birth cries of young stars, and not just any stars, but twins!

Amazing, isn’t it? What appears to the eye at first as a formless blob actually takes on a interesting shape when you start to look more closely. And when you look differently, you see structure that yields more insight on the actual events going on: the birth cries of young stars, and not just any stars, but twins!

When Adam sent me that picture, I wanted to know more about this object, so I dug a bit deeper. I found all the information posted here, as well as much more (like, the jets are ramming the material around them so violently the gas is emitting X-rays 100 times more brightly than the Sun’s X-ray emission, but it’s difficult to detect due to the chokingly thick material surrounding the system).

I love looking at pretty astronomical pictures as much as the next person, but what gets to me is that these are far, far more than just snapshots of the cosmos. These are telling us stories; complicated, wonderful, deep stories of the complexity and history of the Universe, which in turn will certainly yield insight into the birth and evolution of our own Sun and planets. By looking out, we look in, and find that the farther we voyage, the closer to home we get.

Image credits: Adam Block/Mount Lemmon SkyCenter/University of Arizona; Atlas Image obtained as part of the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS), a joint project of the University of Massachusetts and the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center/California Institute of Technology, funded by the NASA and the NSF; Subaru Observatory via ESA; K. Borozdin, Los Alamos National Laboratory, USA

Related posts:

- Hubble celebrates 20 years in space with a jaw-dropper (MUST-SEE image. Trust me here.)

- C-beams off the shoulder of Orion

- Spitzer sees star spew spurious spouts

- Baby stars blasting out jets of matter