My love for planetary nebulae is on record. These expanding shells of gas from dying stars are really beautiful, and I find the physics of the way the gas is ejected to be fascinating. I’ve written about them a lot: check the Related Posts at the end of this article for links.

I like to observe them, too. In the summer there are quite a few that are easy targets, and one of the easiest to find is called M27, the Dumbbell. It’s in the constellation of Vulpecula (the fox), and is big and bright enough to spot easily in binoculars. I’ve probably seen it with my own eyes, no lie, hundreds of times.

But I’ve never seen it like this:

[Click to ennebulenate.]

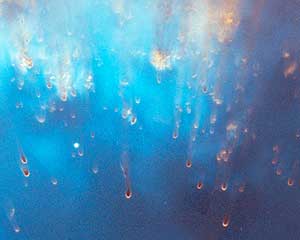

Holy wow! That’s so cool! Literally: this is an infrared image taken by the Spitzer Space Telescope, showing it in light well beyond what our eyes can perceive.

That’s not at all how I’m used to seeing it!  Inset here is an image in optical light (the kind our eyes see) taken by the Kitt Peak 2.1 meter telescope. You can see why it’s nicknamed the Dumbbell; it looks like it has a handle and two curved weights on the ends. The ends are really just bright regions of an outer limb-brightened shell, and the handle is gas inside the nebula.

Inset here is an image in optical light (the kind our eyes see) taken by the Kitt Peak 2.1 meter telescope. You can see why it’s nicknamed the Dumbbell; it looks like it has a handle and two curved weights on the ends. The ends are really just bright regions of an outer limb-brightened shell, and the handle is gas inside the nebula.

In infrared things are so different! Most striking are those incredibly long and thin spokes, stretching away radially from the center. Things like this have been seen before; the Helix nebula, for example, has something similar. But in the Helix they’re fatter and not as long. I wondered at first if perhaps in the Dumbbell these were not actual structures, but instead optical effects like rays from the setting Sun. Maybe the gas in the nebula was blocking the central star’s light, and holes were letting these rays through…

… but nope. I was wrong. These are actual, real, physical structures! Like in the Helix (the image inset here, taken by Hubble), the nebula is littered with dense knots of material, probably condensations in the wind blown from the dying star when it was a red giant. As the outer layers of the star blew away, they exposed deeper, hotter material. The wind from the star increased in speed, overtaking and blowing past the older material the star had emitted centuries before. When the faster wind hit denser knots of gas, it flowed around it, and also vaporized the surface material of the knots. This material then got swept “downwind”, blowing off the knots and forming those long, long streamers. They look a lot like comets, actually, and the physics is similar.

… but nope. I was wrong. These are actual, real, physical structures! Like in the Helix (the image inset here, taken by Hubble), the nebula is littered with dense knots of material, probably condensations in the wind blown from the dying star when it was a red giant. As the outer layers of the star blew away, they exposed deeper, hotter material. The wind from the star increased in speed, overtaking and blowing past the older material the star had emitted centuries before. When the faster wind hit denser knots of gas, it flowed around it, and also vaporized the surface material of the knots. This material then got swept “downwind”, blowing off the knots and forming those long, long streamers. They look a lot like comets, actually, and the physics is similar.

I was surprised the spokes could be so long, but then remembered the image at the top was in the infrared. This is cooler material, and can be traced farther out from the nebula than it could in optical light. Also, as it happens, the spokes in the Dumbbell are just physically really long (they are a couple of light years in length, in fact). I was surprised you could get coherent structures of that length in a nebula like this… but then, planetary nebulae are surprising beasts! That, and their literally other-worldly beauty, are two of the reasons I love them so.

Image credits: Spitzer: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Harvard-Smithsonian CfA; Optical image: REU program/NOAO/AURA/NSF; Hubble image: NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner (STScI), and T.A. Rector (NRAO).

Related posts:

- Hubble sees a gaseous necklace 13 trillion km across

- Warm dusty rings glow around a weird binary star

- Awesome death spiral of a bizarre star