One of the basic principles of modern science is that the physics we understand here, on Earth, work everywhere. This turns out to be a pretty good assumption, because we see it coming true time and again. That knowledge can then be used to figure out things that are happening at very large distances – even well across the Universe.

With that in mind, I present to you LAB-1: a glowing glob of gas as seen by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope:

[Click to, um, englobenate.]

This, however, is no ordinary Space Blob: it’s located at the staggering distance of 11.5 billion light years from Earth! Not very many objects have been seen farther away than this, and it’s one of the single biggest discrete structures seen this far away. It’s about 300,000 light years across – three quintillion kilometers, or three times the diameter of our own galaxy. That’s pretty flipping big.

And although it’s faint to our telescopes, at that distance it must actually be tremendously luminous for us to see it at all. Something is making it glow fiercely, but what? One hint is in the cloud’s name: the LAB in LAB-1 stands for Lyman Alpha Blob. Lyman Alpha (written as Lyman-α) is a specific color of light you get from hot hydrogen gas (just so’s you know, it’s emitted when the electron in a hydrogen atom jumps down from the second to the lowest orbital energy state). Normally, Lyman-α is in the ultraviolet, but this blob is so far away the light is shifted by the expanding Universe into the optical region – that’s why it looks green in the image above.

It takes a goodly amount of energy to create Lyman-α light, so something big is going on here. Maybe this gas cloud is collapsing under its own gravity, and is heated up. Or maybe there are big galaxies inside of it, causing it to glow. How can we tell which is the culprit?

It turns out there is a way: polarization.

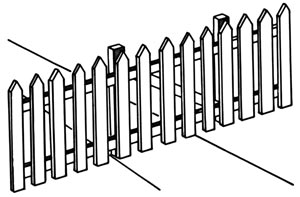

You may already be familiar with this; many sunglasses are polarized (and it’s used to make 3D movies as well). It’s not hard to understand. Imagine two people standing on opposite sides of a tall picket fence. There are spaces between the pickets, maybe 5 cm wide and two meters tall. One person has a sheet of plywood to hand through to the person on the other side. If they hold the plywood horizontally, it can’t get through. Duh. But if they rotate the sheet so that it’s vertical, it passes between the fence pickets easily.

You may already be familiar with this; many sunglasses are polarized (and it’s used to make 3D movies as well). It’s not hard to understand. Imagine two people standing on opposite sides of a tall picket fence. There are spaces between the pickets, maybe 5 cm wide and two meters tall. One person has a sheet of plywood to hand through to the person on the other side. If they hold the plywood horizontally, it can’t get through. Duh. But if they rotate the sheet so that it’s vertical, it passes between the fence pickets easily.

That’s polarization in a nutshell! Light waves can have a rotation too, like the plywood sheet. A polarized filter only allows light with a specific rotation through it, like the vertical slats of the picket fence. Light is usually not polarized, and can be in any old rotation. But some events can align all the waves of light, polarizing it: reflecting off glass or water, for instance. That’s why polarized sunglasses reduce glare; try looking at a reflection off the windshield of a car and then rotate your glasses 90°; the glare goes away.

Light scattered by gas can be polarized, too, which brings us back to LAB-1. If the light is coming from the gas itself, glowing because it’s warm, then it probably won’t be polarized. But if there are galaxies embedded in it, then the light from those galaxies will scatter off the gas in the cloud, and be polarized.

So astronomers used the VLT to stare at LAB-1 for 15 hours, using a polarimeter (a device for measuring polarized light). And what they saw was that the light coming from the cloud was indeed polarized. Not only that, the polarization was strongest in a ring around the center but not at the center itself, just what you’d expect if there were galaxies inside the cloud. The light from galaxies in the center isn’t scattered; it comes straight through the gas and so is not polarized. But the light farther from the center is scattered toward us (think of it like little bullets being ricocheted off of the gas), and does get polarized.

Tadaaa! The gas cloud is being lit up by galaxies inside it. Since the galaxies are young, they’re probably undergoing furious bouts of star formation, which means they’re pouring out Lyman-α. It’s this that’s getting scattered and polarized by the gas cloud.

This was not an easy observation – 11.5 billion light years is a forbiddingly long way away, and even with an 8-meter telescope it was tough to observe – but it was rather straightforward, and quickly cut through two competing ideas. The physics we understand here on Earth still works, even at a numbing distance of over 100 sextillion kilometers! And because of that, a faint green smudge can reveal entire galaxies hidden from view, betrayed by their own activity.

That’s the power of science, folks. Even more than halfway across the Universe, you can’t hide from it.

Image credit: LAB-1: ESO/M. Hayes; picket fence: Wikipedia.

Related posts:

- Voorwerp!

- Found: 90% of the distant Universe (explains Lyman-α light as well)

- Most distant object ever seen… maybe

- Another record breaker: ultra-deep image reveals ultra-distant galaxy