Spitzer Space Telescope is an orbiting infrared observatory. It ran out of coolant a few years back – needed to keep its highly sensitive IR cameras working – but before it did, it took this amazing image of a young star blasting out twin jets of matter:

Neat! [Click to collimatenate.]

The star is called Herbig Haro 34, and is only a few million years old. Stars that young rotate rapidly, have fierce magnetic fields, and thick disks of material surrounding them (out of which planets might form). All these things together help focus twin beams of matter called jets, which blast away at high velocity from the star’s poles. We see these quite often around young stars.

But the jets blowing off of HH 34 are weird. They aren’t symmetric.

Astronomers figured they should be. Sometimes the jets blow out knots of gas or sputter a little. And when that happens, whatever forces acting on the star and disk should act on both jets at the same time. But that’s not the case for HH 34: the jet on the right does the same thing the jet on the left does, but only after a 4.5 year delay!

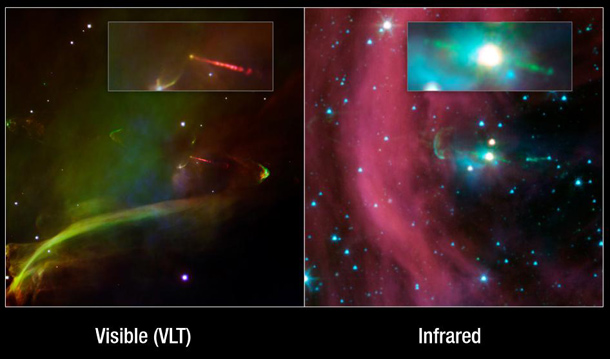

Figuring this out at all wasn’t possible until this Spitzer image was taken. Before, visible light images only showed one jet:

On the left is an image from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope compared to Spitzer. In the VLT image you can see the jet on the right, but the jet on the left is obscured by thick dust (though you can see the bow shock at the end of the jet as it slams to a halt after plowing through all the gas and dust surrounding the star). Once Spitzer was aimed HH 34’s way, the second jet was viewable – IR can pierce through all that dust – and the timing could be determined. You can watch an amazing animated GIF showing the motion of knots in the visible jet taken by Hubble Space Telescope, too.

So what’s causing the delay? It’s not clear. But, it must have to do with the disk; anything coming from the star itself should happen simultaneously to both jets. Maybe there is some asymmetry in the disk that allows one jet to precede the other. If there is some event happening in the disk, then it must somehow “talk” to both jets, delaying one over the other.

That sort of information propagates through material at the speed of sound. Using the known speed of sound in disk material like that, and the time delay of 4.5 years, astronomers have determined that whatever it is focusing the jets has to be smaller than about 500 million kilometers (300 million miles) in radius – about three times the distance of the Earth to the Sun. If it were much bigger or smaller than that, the delay wouldn’t be the right amount. Before these Spitzer observations, that size was estimated to be more than 10 times larger, so astronomers have been able to greatly narrow down the volume of space in which these jets are generated.

Herbig Haro 34 is about 1400 light years away in the direction of Orion, where lots of other young stars are being formed. The phase in a star’s life when it blows off jets like these is short, so it’s an interesting event to understand. It’s possible, even likely, that 4.5 or so billion years ago, our own Sun looked very much like HH 34 when it was a baby. Given that, and what I know about human babies, it’s hard not to see the analogy of, um, oh how to phrase this delicately? Having material blowing out of both ends.

Imagine having a baby that could do that over several light years! I’ll have to remember that the next time a new parent friend complains about the cost of diapers or burping cloths. It could be a lot worse.

Image credits: Spitzer/VLT: NASA/JPL-Caltech; Hubble animations: NASA/ESA Hubble and Patrick Hartigan

Related posts:

- Baby stars blasting out jets of matter

- C beams off the shoulder of Orion

- Hubble celebrates 20 years in space with a jaw dropper