Could there be another planet lurking in the dark, frigid outskirts of the solar system?

This isn’t as silly as it seems at first. No, I’m not talking Nibiru or any of that other nonsense (and it is nonsense), I’m talking about an actual planet, Earth-sized or so, that could be orbiting the Sun well beyond Pluto Neptune.

Why would we think there might be one out there?

We see some stars in the midst of forming planets. The stars are surrounded by thick disks of material, and in some we can actually see gaps in the disk, dark rings like the gaps in Saturn’s rings, that we think are due to forming planets gobbling up material in the ring. You’d think the disk would fade away with distance from the star, like our air gets thinner with altitude. But some disks appear to have sharp outer edges. This can be caused by a planet orbiting outside the disk; its gravity sweeps up the material and over time cleans up everything farther out. In one disk, this sharp boundary indicates a planet 200 AU out (an AU is the distance of the Earth to the Sun, about 150 million kilometers or 93 million miles).

Neptune orbits at 30 AU from the Sun, so 200 AU is a long way out. Could a planet like that have formed in our solar system? Maybe. Thing is, while our proto-planetary disk has been gone for billions of years, we do have lots of objects out past Neptune: the Trans-Neptunian Objects (they have lots of names, including Kuiper Belt Objects). These are basically giant balls of ice, some hundreds of miles across. As a group they form a puffy disk of objects stretching from Neptune’s orbit outward… but they seem to abruptly stop past about 50 AU out from the Sun. That’s called the Kuiper Cliff, the cause of which is unknown. Incidentally, it’s not because they’re too faint to see (that is, they’re there but we can’t spot them); at that distance we should have spotted lots of them by now.

Not only that, but a lot of these objects have orbits that are tilted more and are more elliptical than you’d expect if they just formed a long time ago and were left alone. Their orbits don’t bring them in very close – they tend to stay outside of Neptune’s orbit – but again, this is something that needs to be explained.

Could it be that there is another massive planet orbiting the Sun, way out there, which has swept up the objects gravitationally, creating the Kuiper Cliff and tossing the iceballs into tilted, oval orbits?

A newly released paper shows that may very well be the case. A team of scientists ran a whole mess of simulations, and found that a small planet (in this case, around half the size of the Earth) could have formed inside Neptune’s orbit (where there was plenty of material in the early solar system), gotten tossed into a bigger orbit by Neptune, and then knocked around the orbits of the iceballs, distorting their orbits and creating the Kuiper Cliff.

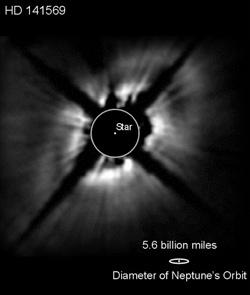

This idea is not new, but this new research is a provocative indicator of such a planet’s likelihood of existence. I’m not saying it’s out there, but it’s worth looking for. In fact, I’ve been saying that since about 1998 or so, when I worked on Hubble and was involved with a project that found a truncated disk around another star. I even worked with another astronomer on the team to investigate whether the robotic telescopes used to look for Near Earth Asteroids could spot such a planet.

It’s not all that easy. It wouldn’t be too faint to see, necessarily, but it’s a big sky. At that distance, the planet would move slowly, and the orbital motion would be hard to distinguish given the procedures used by NEA searches. We tried to convince some of them to modify their software to look for Planet X (yes, why not, though now it would be Planet IX), but we were met with mixed success. The fact that no one has discovered this planet shows you that this is still hard to do.

But maybe, just maybe, with this new research we’ll get people looking more seriously. It’s amazing to me that we can understand so much about galaxies and hugely distant objects, but find that there may be surprises waiting for us in our own back yard.