Atlas Obscura on Slate is a blog about the world’s hidden wonders. Like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

The appeal of the mystery of D.B. Cooper, who jumped out of a plane with $200,000 in cash and two parachutes in 1971 and was never found, is that it may as well be a myth.

Cooper knew enough to jump at 10,000 feet, high enough to obscure his landing spot but low enough so that he could survive. He knew that the Boeing 727 plane he had hijacked had a rear exit, unlike similar planes and similar models. He apparently knew how to use a parachute but only asked for “front” and “back” parachutes, suggesting to some at least that he wasn’t exactly a professional. He also knew, high in the sky, that that might be Tacoma, Washington, down below.

He knew enough, in other words, to get the job done, but not enough to suggest he had any kind of special skills. He was a man in a suit who smoked and drank bourbon and, theoretically, could have been any man in America who wore a suit and smoked and drank bourbon. His only principles were stacks of bills and swagger, and his only political cause was escaping. Was Don Draper D.B. Cooper? (Spoiler alert.) No. But he could’ve been.

This summer, the FBI announced that it was officially closing the case on D.B. Cooper.* A 44-year investigation into his disappearance had come to an end, after dozens of suspects, and hundreds of tips, and, in 1980, the only concrete proof that D.B. Cooper might have in fact made it to the ground and not simply vanished into thin air: some money, found by an 8-year-old boy along the Columbia River, not far from where Cooper might have landed.

There was $5,800 in tattered bills in all, meaning that D.B. Cooper made off with at least $194,200, or died trying. His parachute has never been found. His body has never been found. One-hundred ninety-four thousand, two hundred dollars in bills have never been found, bills with serial numbers that financial institutions across the country have been keeping an eye out for since 1971.

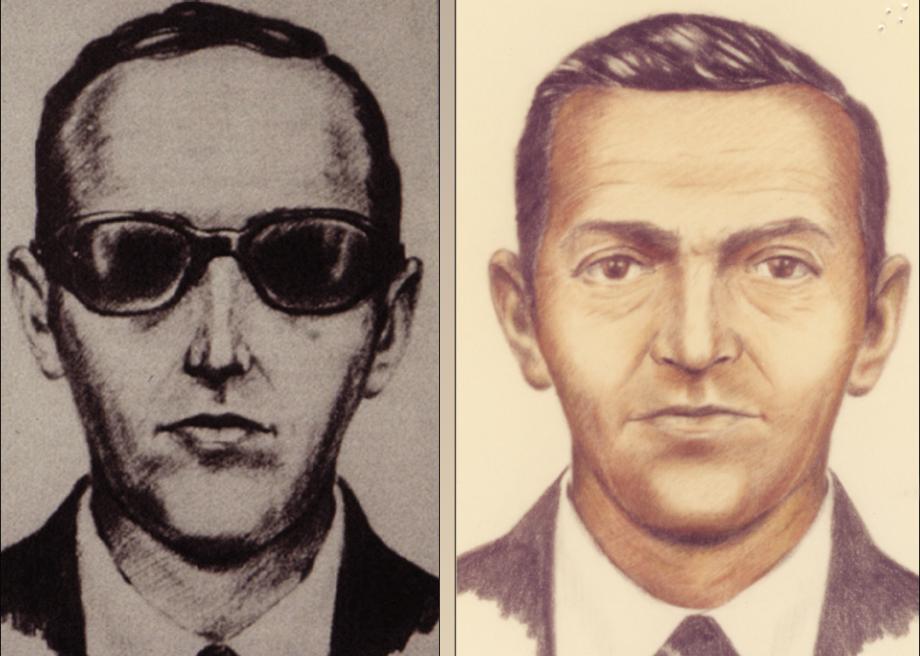

There have been theories, of course, about who D.B. Cooper was. He certainly wasn’t Dan Cooper, the name he gave airline officials when he bought his ticket. (He became D.B. Cooper because of a reporter’s mistake. Perhaps because the initials somehow heighten the myth, it stuck.)

Was he a former paratrooper? Was he a disgruntled employee of Northwest Airlines, which owned the flight that D.B. Cooper skyjacked? Was he simply a drifter with a plan?

We don’t know. What we do know is this: that on the day before Thanksgiving 1971 early in the afternoon Cooper bought a one-way ticket in Portland, Oregon, to fly to Seattle, a 30-minute flight. On the plane, he bought a bourbon and lit a cigarette, then passed a note to a flight stewardess claiming that he had a bomb. He then opened a bag just enough for her to see some red cylinders wired to what looked like a battery.

Cooper then laid out his demands: a stop at the Seattle-Tacoma Airport, a refueling of the plane, four parachutes, and $200,000 in cash, which authorities agreed to. D.B. Cooper allowed the passengers to exit in Seattle and, by 7:40 p.m., the plane was back in the air. Around a half-hour later, with the crew behind closed doors in the cockpit, D.B. Cooper is thought to have jumped.

Two fighter planes tracking the 727 never saw him, but by the time it landed in Reno, Nevada, at around 10:17 p.m. that day, authorities surrounded the airplane and then searched inside. The man who called himself Dan Cooper was gone.

Cooper had originally demanded to be flown to Mexico City, with the parachutes requested perhaps as a precaution or backup plan. But his demands were too specific—they had to be civilian parachutes, not military—to suggest that he never intended to use them at all. He used at least one parachute to wrap and carry the money, the FBI has said. He also left one behind.

Simulations, extensive ground searches, tips from the public—none of it worked. And the FBI has mostly concluded that D.B. Cooper’s story ended the night it began. Experts tend to agree, as Cooper jumped out of plane into a heavy storm and onto some of the toughest terrain in America during temperatures in the high teens. Cooper is probably, it’s safe to say, dead.

But that doesn’t mean there haven’t been suspects. One, in particular, stands out: Kenneth Christiansen, a former paratrooper who worked as Northwest Airlines around the time of the skyjacking. An extensive New York magazine investigation into Christiansen’s possible involvement in 2007 lays out a compelling case. As a former World War II paratrooper, he certainly had the skills. In addition, as some of Christiansen’s friends and family told New York, he always seemed to have money, more than what you’d expect from a guy who was a flight attendant. And the FBI’s longtime former lead agent on the case, Ralph Himmelsbach, told New York that if he had known what we know now about Christiansen, who died in 1994, he would have “labeled him a ‘must-investigate’ ” back then.

Still, the case against Christiansen remains circumstantial. There’s simply no physical evidence that ties him to the crime, and, 44 years later, it’s pretty unlikely that any is going to show up. (Brendan Koerner, for instance, author of The Skies Belong to Us, weighed in on Twitter that the corpse was likely eaten by animals.) But maybe we don’t really want to trade the idea of D.B. Cooper for the reality of Kenneth Christiansen, a flight attendant who lived in Bonney Lake, Washington, who liked to eat out for every meal. No Don Draper, in other words, but a mundane solution to a decadesold puzzle—a solution we may not have needed all along.

If you liked this, you’ll probably enjoy Atlas Obscura’s New York Times best-selling book, which collects more than 700 of the world’s strangest and most amazing places: Atlas Obscura: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Hidden Wonders.

*Correction Jan. 4th: This article originally misstated the date of the FBI’s announcement. (Return to the corrected sentence)