Atlas Obscura on Slate is a blog about the world’s hidden wonders. Like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Perhaps the most impressive thing about the anatomical votives of central Italy are the sheer numbers in which they were found.

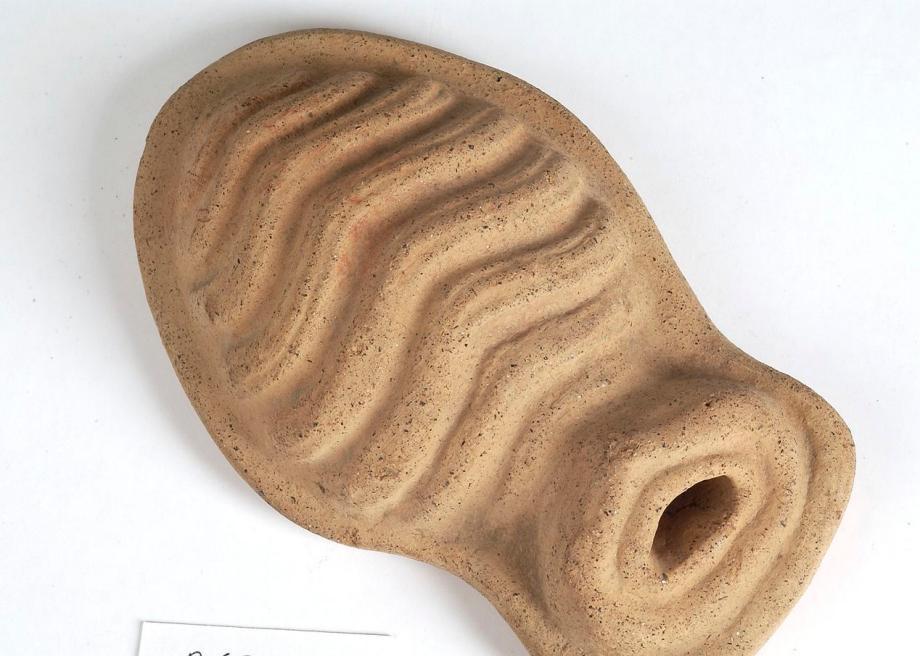

One site contained 1,654 votive feet, made of terra cotta. Another had more than 400 terra-cotta wombs. At Ponte di Nona, there were 8,395 votives recovered in the 1970s—of the 6,171 that were identifiable body parts, 985 were heads, about as many were eyes, and 2,368 were feet. Overall, at about 150 sites, archaeologists have uncovered tens of thousands of feet, legs, arms, hands, heads, eyes, ears, breasts, uteri, vulvae, phalluses, and sometimes whole midriff sections, with indistinct organs exposed.

Scholars of ancient Italy have known about these devotional offerings for decades now, but they’re still wondering: Why exactly did people leave these votives for the gods?

Anatomical votives of this sort have also been found in Greece, but they were most popular in one specific place, during one specific time—on the western coast of central Italy, from about the 4th century B.C. to the 1st century B.C. Most of the tens of thousands of surviving votives that archaeologists have found were left in pits, often containing thousands of body parts. Rebecca Flemming, a British scholar who writes about the votives in a new book, calls these “organized clear-outs of the votive clutter”—respectful burials of past offerings meant to clear temple space for new ones.

Before they were buried, these votives would have crowded the walls, ceilings, and floors of temples—they’re designed for display. Many of them have holes that could have been used to hang them on a hook or looped through with some sort of line to suspend from a wall or ceiling. Others had pedestals or were made so they could lean against a wall. Many of the votives were somewhat standardized and made from molds, although they also varied in size and design. It’s also likely that visitors left anatomical votives made of materials other than clay; terra cotta just happens to be a material with a long shelf life.

It’s clear that these anatomical votives were connected in some way with health and well-being, but for years scholars have debated exactly who used them and how. Once it was thought that the votives were primarily used by rural people, but Flemming argues that it was a “wide-spread, accessible, and inclusive,” popular inside cities and far out into the countryside and available both to elites and lower classes.

Some scholars believe that the votives reflects pleas for the healing of particular body parts or were thank-you gifts for prayers answered. Some shrines may have specialized in particular illnesses—at least that’s one explanation for why one place might have a great concentration of hands, another a great concentration of eyes, and another a great concentration of uteri.

It’s an easy leap to make when a temple to a goddess connected to fertility is full of terra-cotta wombs. At one site, when the wombs were X-rayed, they were found to have small spheres inside, apparently representing embryos—either wishes fulfilled or requests for the future.

But some scholars think these anatomical votives shouldn’t be taken quite so literally. Feet votives could be connected to travel, for instance; eyes and ears could represent something more conceptual than eye and ear pain. Did heads represent headaches—or the whole persons? Or perhaps a soul sickness rather than a simple physical pain?

Part of the mystery comes from the lack of written sources that explain exactly what was going on here. The practice faded as social and political conditions in the area changed: People began concentrating more in cities, and written votives became more popular.

Indeed, scholars still have plenty to argue about: A new book is coming out in 2017 that’s dedicated to “new questions about what constitutes an anatomical votive” and “how they were used and manipulated.”

There will probably always be questions, though, about these mass burials of clay body parts.

If you liked this, you’ll probably enjoy Atlas Obscura’s New York Times best-selling book, which collects more than 700 of the world’s strangest and most amazing places: Atlas Obscura: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Hidden Wonders.