Atlas Obscura on Slate is a blog about the world’s hidden wonders. Like us on Facebook and Tumblr, or follow us on Twitter.

So you want to marry a ghost.

In some societies, it’s possible—with a few caveats. Posthumous marriage—that is, nuptials in which one or both members of the couple are dead—is an established practice in China, Japan, Sudan, France, and even the United States, among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. The procedural and legal nuances of each approach vary wildly between cultures, but here is an overview of how to tie the knot with someone who isn’t quite alive.

China: Skewed Sex Ratios and Grave Robbery

Although Chinese dating and marriage practices are slowly changing under the influence of technology and online dating, traditional, family-oriented values still rule. Matchmaking, via meddling parents and/or a marriage broker, is big business. To be female and unmarried at 30 is to be a “leftover woman.”

The 1978 implementation of the one-child policy has complicated the marriage market somewhat due to the societal preference for baby boys. A 2011 study found that the sex ratio among newborns rose from 105 males per 100 females in 1980 to over 120 males per 100 females during the 2000s. This skewed ratio has resulted in an overabundance of single men.

According to Chinese custom, older sons ought to marry before their younger brothers. If an older brother should die unmarried at a young age, however, there is a solution that keeps the social order intact: ghost marriage. In China, and among the Chinese in Taiwan and Singapore, ghost marriages are performed to address a variety of social and spiritual ills. Chief among these are the desire to placate the restless spirits of those who go to their grave unmarried. “Ghosts with families are liable to direct their discontent within the family circle,” writes Diana Martin in Chinese Ghost Marriage, “and it is here that ghost marriage becomes operative.”

A family whose son or daughter has died at a young age may come to believe that the deceased person is communicating a desire to be wed. This message can take the form of a spirit wreaking general havoc on the family, such as causing illnesses that do not respond to conventional treatments. A restless bachelor ghost may also express his desire to be married by appearing in a family member’s dream or while being channeled through a spirit medium during a séance.

Most ghost marriages are conducted to unite the spirits of two departed souls, rather than wedding a dead person to a living one. Though it may seem harmless to conduct a postmortem ritual designed to make two ghosts happy, the practice of matchmaking dead men with worthy ghost brides has occasionally resulted in criminal depravity. In March 2013, four men in northern China were sentenced to prison for exhuming the corpses of 10 women and selling them as ghost brides to the families of deceased, unmarried men. The women’s bodies were intended to be buried alongside the dead men, ensuring eternal companionship.

For deceased women, ghost marriage offers social and spiritual advantages in China’s patrilineal society. A woman who dies single, without having had children, has no-one to worship her memory or tend to her spirit. According to Chinese tradition, a dead woman cannot be memorialized within her family’s home. Her spirit tablet (a memorial to a dead person that is displayed in a home altar that honors the family ancestors) is forbidden from being placed among the family in which she grew up. A deceased married women, by contrast, gets to have her spirit tablet put on display in her husband’s home. Ghost marriage, therefore, ensures that a woman’s spirit can be worshipped by bringing her into the family of a husband who has been chosen for her after her death.

If a heterosexual couple is engaged, and the man dies before the wedding, the woman can engage in a ghost marriage by marrying her fiancé’s spirit. During the ceremony, a white rooster stands in for the groom. According to Lucas J. Schwartze in Grave Vows: A Cross-Cultural Examination of the Varying forms of Ghost Marriage among Five Societies, the bird also rides in the bridal carriage post-ceremony and thereafter accompanies the bride to formal dealings with the groom’s family. Such cases are rare due to the requirements placed on the bride, who must then move in with her dead husband’s family and take a vow of celibacy.

Whether it involves a live person or not, ghost marriage is not legal in China—NBC News reports that it was outlawed during the reign of Chairman Mao—but the ritual endures, particularly in the northern regions of the country.

Japan: Darling Dolls for the Afterlife

In her 2001 article “Buy Me a Bride”: Death and Exchange in Northern Japanese Bride‐Doll Marriage, Ellen Schattschneider sums up the philosophy behind ghost marriage in Japan:

“Persons who die early harbor resentment toward the living. Denied the sexual and emotional fulfillment of marriage and procreation, they often seek to torment their more fortunate living relatives through illness, financial misfortune, or spirit possession. Spirit marriage, allowing a ritual completion of the life cycle, placates the dead spirit and turns its malevolent attention away from the living.”

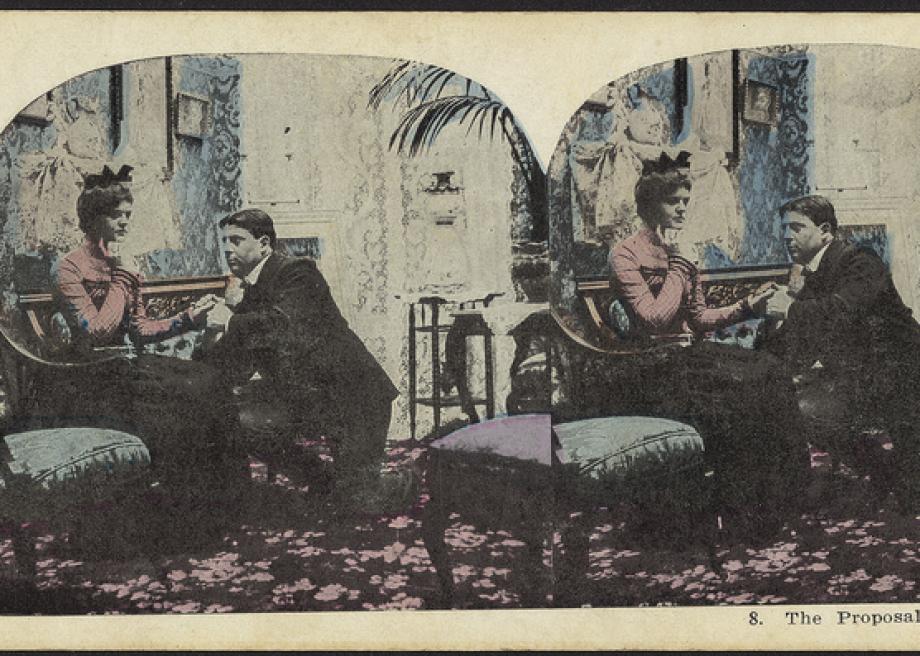

Photo: Batholith/Public Domain

The main factor distinguishing Japanese ghost marriage from its Chinese counterpart is the incorporation of non-human spouses. A deceased person is not married to a dead person, nor to a living one, but to a doll. The most common ghost marriage is between ghost man and bride doll, but ghost women are occasionally united with tiny, inanimate grooms.

According to Schattschneider, Chinese-style ghost marriage, between a living woman and deceased man, formerly took place in Japan, but was replaced in the 1930s by man-doll marriage. (This shift happened due to an increase in young, single men dying during war and the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. The high number of casualties made it too difficult to find enough live brides for them all.)

During a bride doll wedding ceremony, a photo of the dead man is placed in a glass case alongside the doll to represent their union. The tableau stays in place for up to 30 years, at which point the man’s spirit is considered to have passed into the next realm. The symbolic companionship is designed to keep the ghost husband calm and prevent him from causing unrest within his living family.

France: A Legal Option for the Bereaved and Betrothed

France is the rare country in which it is explicitly legal for a living person to marry a dead one. Article 171 of the French civil code—the laws by which the country is governed—states that “the President of the Republic may, for grave reasons, authorize the celebration of the marriage where one of the future spouses is dead.”

Naturally, there are caveats: the living person must prove that the couple intended to marry, and has to obtain permission to wed from the deceased’s family. If the president chooses to grant the wedding request, the marriage becomes retroactive from the day before the deceased person’s death. The living spouse does not receive the right to intestate succession—that is, they do not acquire the dead person’s assets or property. But if a woman is pregnant at the time of her partner’s death, the child, when born, is considered an heir to the deceased.

Though the civil codes of France were introduced during Napoleon’s reign, the article enabling postmortem matrimony is a relatively recent addition. The story behind the addition begins with a disaster: on December 2, 1959, the Malpasset Dam just north of the French Riviera collapsed, unleashing a furious wall of water that killed 423 people. When then president Charles de Gaulle visited the devastated site, a bereaved woman, Irène Jodard, pleaded to be allowed to marry her dead fiancé. On December 31, French parliament passed the law permitting posthumous marriage.

Hundreds of grieving French fiancées have since married their departed sweethearts. (And that’s “fiancées” with two Es—a study of French posthumous marriages that were granted between 1960 and 1992 found that, of the 1654 wedding requests, almost 95 per cent came from women.)

Posthumous marriages continue to be granted in France, usually under heartbreaking circumstances. In 2009, 26-year-old Magali Jaskiewiczmarried her deceased fiancé and father of her two children Jonathan George, who died at 25 in a car accident two days after asking her to marry him.

Sudan: Weddings in the Wake of Fatal Feuds

Within the Nuer ethnic group of southern Sudan, ghost marriage happens in a very particular way. “If a man dies without male heirs, a kinsman frequently marries a wife to the dead man’s name,” writes Alice Singer inMarriage Payments and the Exchange of People. “The genitor [biological father] then behaves socially like the husband, but the ghost is considered the pater [legal father].”

In other words, the woman marries a living man, who stands in for the dead one. Any offspring, while biologically fathered by the living husband, are considered to be descendants of the dead man.

This arrangement, which often is carried out when a Nuer man dies in a feud, is conducted in order to secure both the property and ongoing lineage of the dead man. The woman receives a payment at the time of the ghost marriage—a fee known as the brideprice—which may include “bloodwealth” money from those responsible for the death of the man as well as payment in the form of cattle that once belonged to the deceased man. In this way, Nuer posthumous marriages maintain the social order by redistributing wealth and property.

Mormonism: Marriage by Proxy

According to the doctrines of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, marriage is eternal and death is but a blip. Matrimony, known as “sealing” in Mormonism, binds a couple to one another for the rest of their lives and beyond, provided that both spouses conduct themselves according to the LDS interpretation of the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Photo: Bryan Mills/Flickr

The Mormon belief that marriage is eternal allows for a wedding ceremony to be performed on those who have already died, in a manner similar to posthumous Mormon baptisms. These proxy sealing ceremonies, which take place in an LDS temple, are intended to be initiated only by the descendants of those concerned. But as Max Perry Mueller wrote in a 2012 Slate article, that’s not always the case. Mueller detailed the case of Thomas Jefferson and one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. Neither were Mormon during their lifetimes. They were also not married. But in the eyes of the LDS church, they are now sealed to one another for eternity, having been both posthumously baptized and posthumously wed.