Atlas Obscura on Slate is a blog about the world’s hidden wonders. Like us on Facebook, Tumblr, or follow us on Twitter.

Amid the seemingly endless white monotony of Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf, encased in a cairn made of snow, lie the bodies of three explorers who came agonizingly close to triumph. When they were discovered on Nov. 12, 1912, almost a year after they had bid farewell to their last support team, the fate of Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s trip to the South Pole became clear.

Scott’s expedition, officially known as the British Antarctic Expedition, set off from Wales in June 1910. The chief aim of the ambitious trip was to be the first to reach the South Pole. No one in the world had yet claimed that achievement, although Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen was a definite threat—he left Oslo on his own South Pole expedition 12 days before Scott’s departure. The pressure was on.

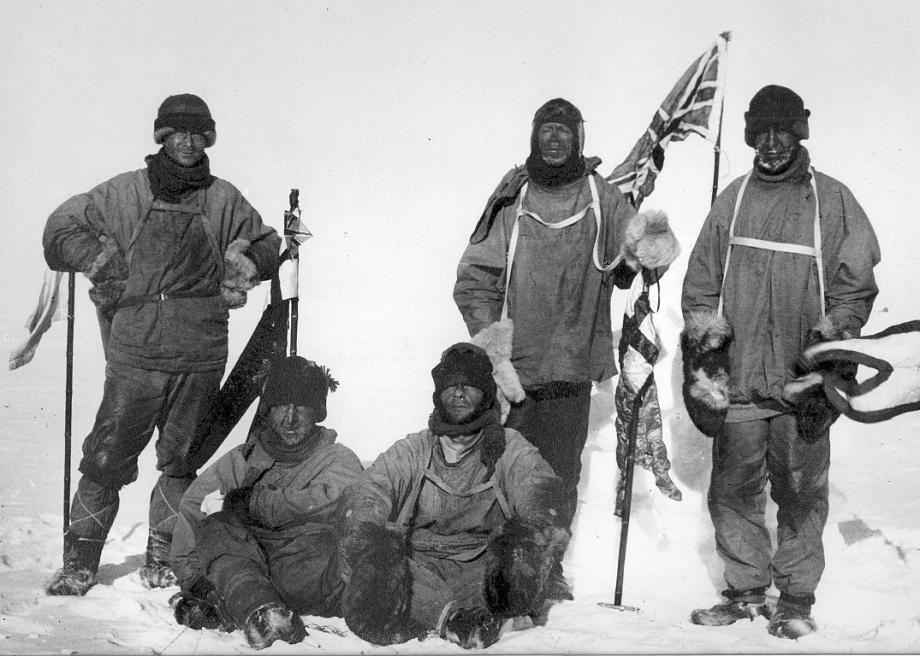

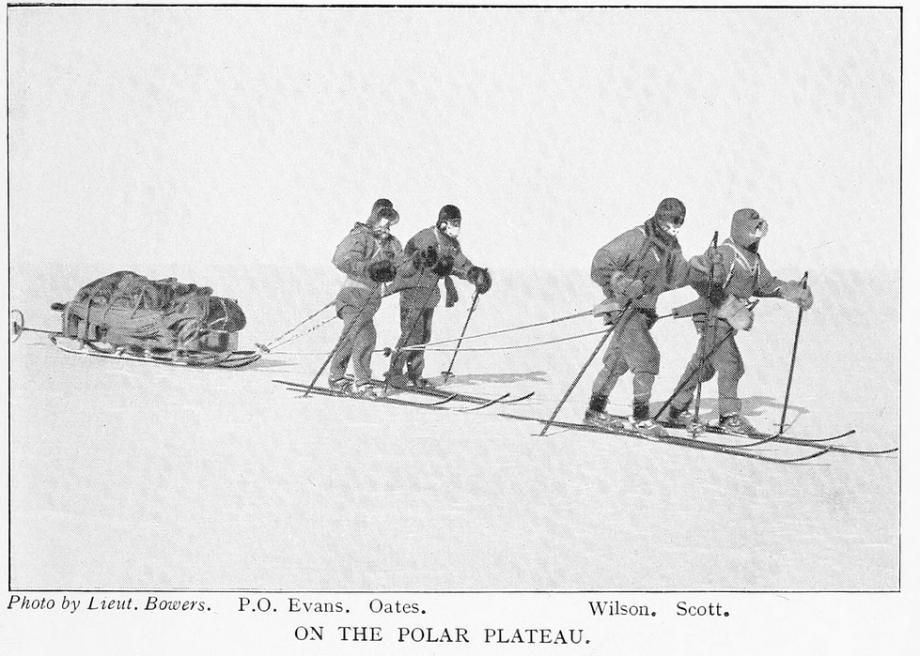

On Sept. 13, 1911, after months of building shelters, laying depots filled with food and fuel, and conducting scientific research, Scott was ready for the trip to the Pole. Sixteen men divided into four teams began the journey, accompanied by sledges, dogs, and ponies. At predetermined points along the way, three of the sub-teams turned back, leaving Scott and four of his most resilient men to complete the journey to the South Pole and back.

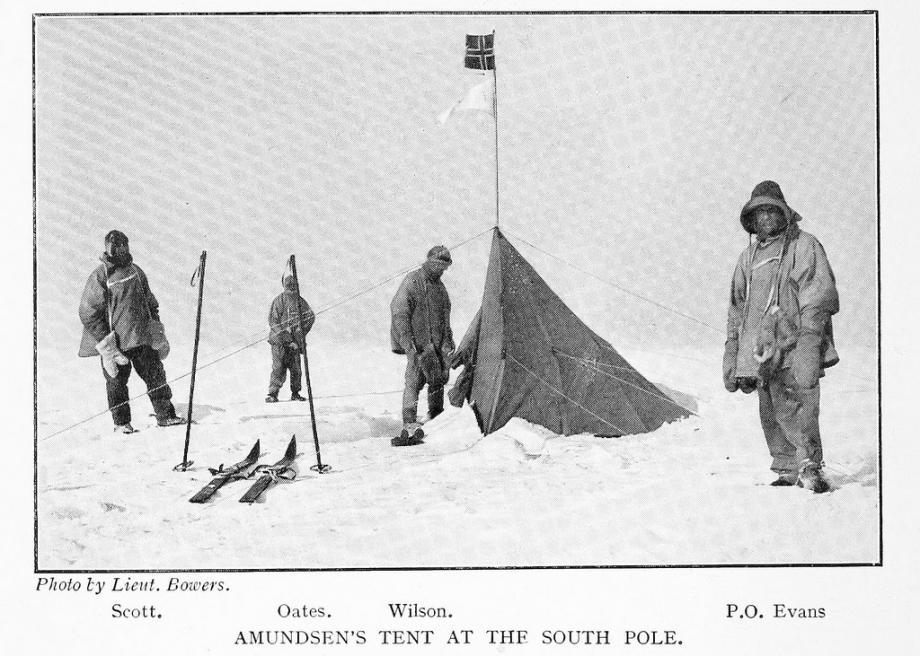

Scott, Henry Bowers, Edgar Evans, Titus Oates, and Edward Wilson had been slogging through the snow for a miserable four months when, on Jan. 16, 1912, they finally got within 15 miles of the South Pole. There that they spotted a black speck in the distance. It was a flag, planted at the South Pole a month earlier by Roald Amundsen.

Photo: Originally from The Great White South (1922), by Herbert Ponting. Sourced from Public Domain Review on Flickr under Creative Commons

The disappointment weighed heavily on their exhausted shoulders, but Scott held out hope—although they wouldn’t be the first to reach the Pole, they could still be the first to send the news back home if they hurried back.

The return journey, however, as chronicled in Scott’s diary, is a heartbreaking account of dashed hopes, self-sacrifice, and staying determined until the bitter end. By the time they set off for home, the team was in poor health. Evans, in particular, was struggling: Scurvy, severe frostbite, and a head injury sustained during a fall on the ice had turned him into a different person. “Evans has nearly broken down in brain, we think,” wrote Scott on Feb. 16, 1912. He died the next day.

A month later, amid plummeting temperatures, blizzards, and poor visibility—it was Oates who was in dire straits. His severely frostbitten feet made walking near impossible. Guilt-ridden and certain of his imminent death, 31-year-old Oates made a decision that has since become the ultimate example of noble self-sacrifice. On the evening of March 17, during a blizzard, Oates rose in the tent, turned to Scott, and uttered his last words: “I am just going outside and I may be some time.” His body was never found.

The end was near, and Scott knew it. Two days after Oates walked into oblivion, a blizzard hit and did not relent for over a week. Scott, Evans, and Wilson were trapped in their tent with little food, scant fuel, and a sober awareness of their fate. Amazingly, they were just 11 miles from a depot stocked with food and fuel. In better weather, the team could have easily covered 11 miles in a day, but the blizzard made further travel impossible. Weakened and out of options, the men lay in their sleeping bags and waited to die.

The diary entries and letters that Scott wrote in this tent are terribly poignant and evocative. “Had we lived,” he wrote on the last day, “I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale.”

In a letter addressed “To my Widow,” Scott wrote: “What lots and lots I could tell you of this journey. How much better has it been than lounging in too great comfort at home.”

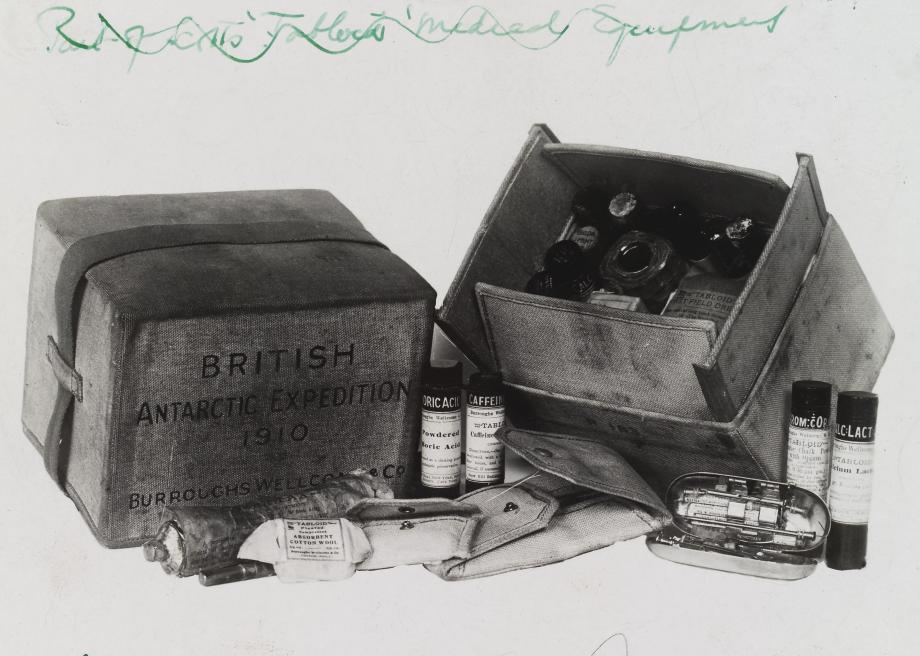

Photo: Wellcome Library, London/Creative Commons

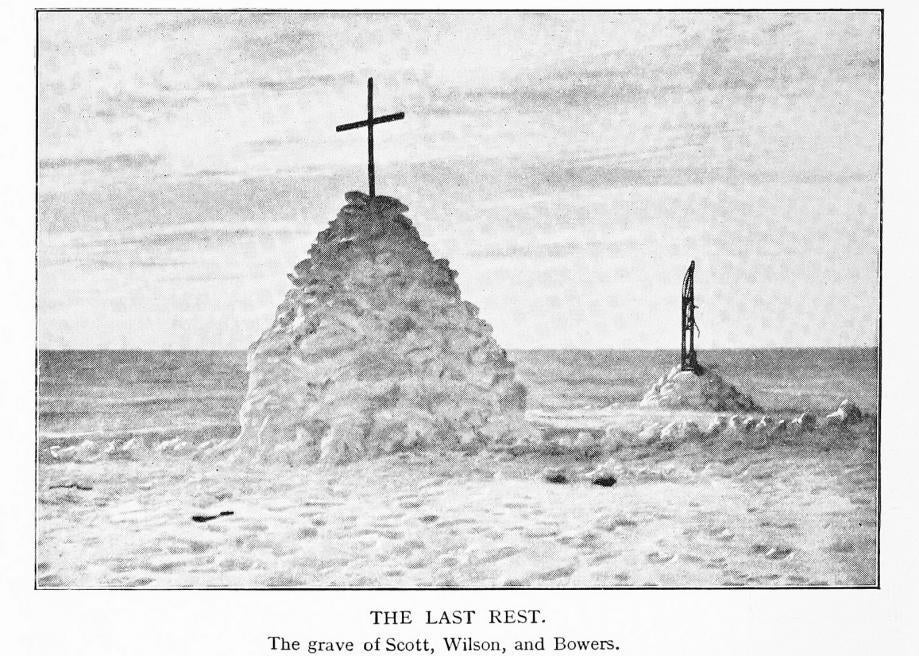

Scott’s diary was found on Nov. 12, 1912, when a search party finally reached the tent and discovered the three men still cocooned in their sleeping bags. By that time they had been dead for over seven months. In his book The Worst Journey in the World, Apsley Cherry-Gerrard—one of the 16 men on the initial leg to the South Pole—described the makeshift funeral he and his three search party members conducted.

“Atkinson read the lesson from the Burial Service from Corinthians,” he wrote. “Perhaps it has never been read in a more magnificent cathedral and under more impressive circumstances—for it is a grave which kings must envy.”

When it came time to leave the bodies, the search team removed the poles from the tent, allowed it to collapse on their fallen colleagues, and built a cairn of snow on top. To finish, they took a pair of skis and fashioned a cross, which they placed atop the cairn. Having read Scott’s diary and learned the fate of Oates, they searched for him, but couldn’t find a trace. The team built another cairn near the tent to honor him.

Photo: Originally from The Great White South (1922), by Herbert Ponting. Sourced from Public Domain Review on Flickr under Creative Commons

Given the harrowing demise of Scott and his South Pole team, it’s not surprising it took over 100 years for anyone to reattempt his journey. But in October 2013, after 10 years of planning, Ben Saunders and Tarka L’Herpiniere embarked on a quest to retrace Scott’s steps and complete the unfinished last leg. Departing from Scott’s hut on the coast of the Ross Sea, Saunders and L’erpiniere spent 104 days skiing to the South Pole and back, each pulling a sledge weighing up to 440 pounds.

On Feb. 7, 2014, the duo became the first to complete Scott’s journey—1,800 miles on foot, walking an average of 17 miles per day in wind chill as low as -50 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s amazing the innovations a century brings: Instead of writing journal entries in pencil at the end of each day, Saunders blogged on a laptop customized to withstand the cold. At the end of each day, he uploaded text, photos, videos, and GPS stats to a website that tracked their movements.

Scott’s expedition diary has been published in blog format at the University of Cambridge’s Scott Polar Research Institute site. The blog detailing Saunders and L’Herpiniere’s journey is online at ScottExpedition.com. For a harrowing insight into the triumphs and agonies of polar exploration—and a look at how extreme trekking has changed in a hundred years—read one after the other. Visualize the terrain by looking at Antarctica up close via Google Street View.

Visit Atlas Obscura for more on Scott’s snow tomb and other relics of Antarctic exploration.

Photo: Originally from The Great White South (1922), by Herbert Ponting. Sourced from Public Domain Review on Flickr under Creative Commons

Other astounding places in Antarctica: