Atlas Obscura on Slate is a blog about the world’s hidden wonders. Like us on Facebook, Tumblr, or follow us on Twitter.

The Victorian era was prime time for taphophobics—those afflicted with a fear of being buried alive. At the time, medical technology had progressed far enough for doctors to realize that they may have been putting people in the ground prematurely—an act known as vivisepulture—but not far enough to definitively declare death.

This anxiety-riddled state of affairs is illustrated in this account from 1842, as documented in Premature Burial and how it May be Prevented: With Special Reference to Trance, Catalepsy, and Other Forms of Suspended Animation:

“A man apparently died, and his death was certified to both by the attending physicians and the medical inspector; he was put into a coffin, and the religious ceremonies were performed in good style. At the end of the funeral service, and as he was about to be buried, he awoke from his trance. The clergy and the undertakers sent in their accounts for the funeral expenses; but he refused to pay them, giving as his reason that he had not ordered them; whereupon he was sued for the money.”

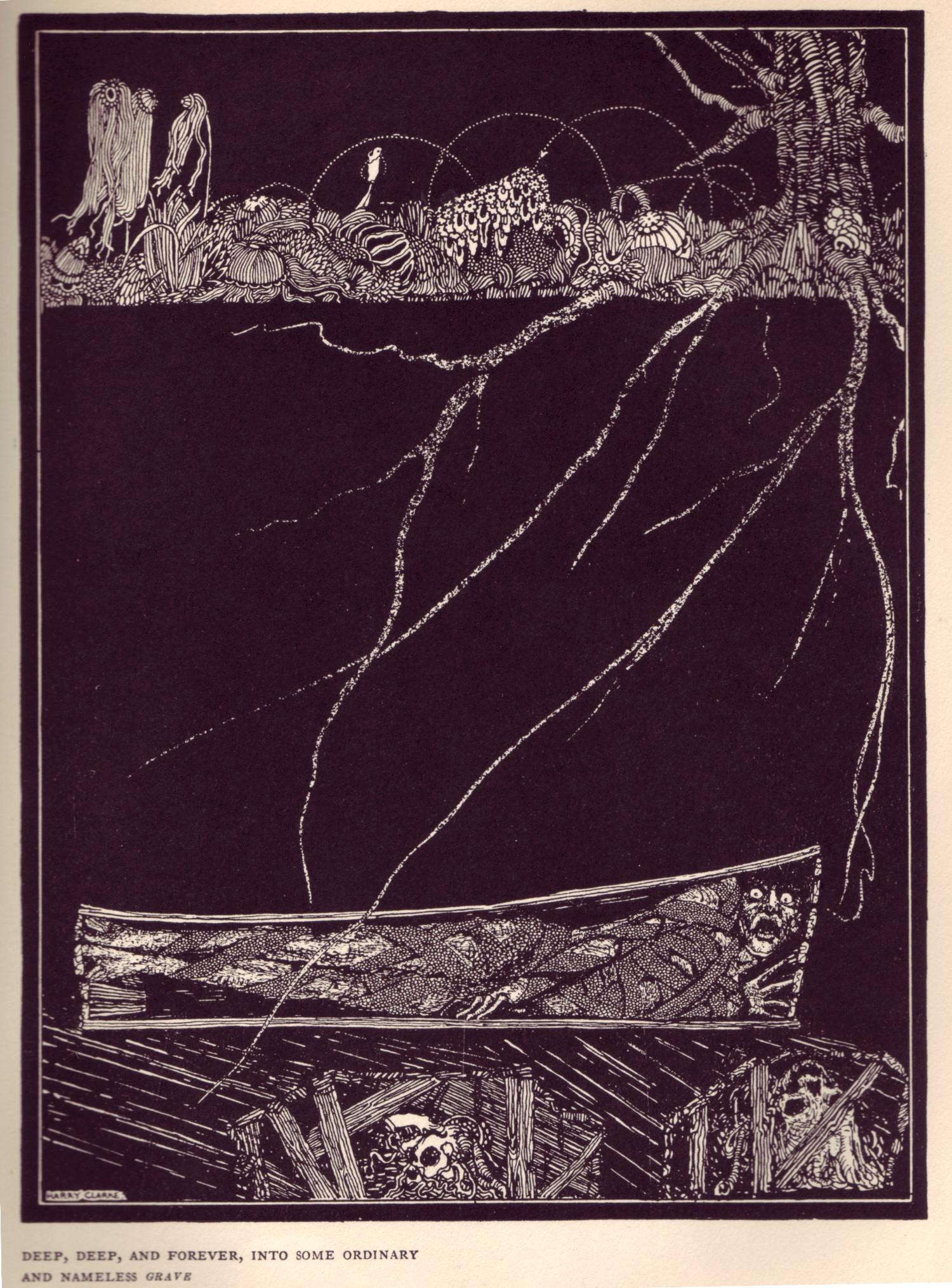

Tales of being buried alive permeated popular culture in the mid-19th century. Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Premature Burial, about a man obsessed with the idea of falling into a trance and being mistakenly interred, was published in 1844. A subsequent printing came complete with this terrifying illustration:

A variety of unusual methods were used to test for signs of life among the apparent dead. Tobacco smoke enemas were commonly employed in 18th-century Europe to try to resuscitate the apparently dead. Smoke—blown through a pipe into the rectum using a bellows or from the mouth of an unflinching rescuer—was thought to bring people back from the brink of death. Drowning victims were subjected to smoke enemas after being hauled from the water, with occasional, and coincidental, success.

Waiting mortuaries, in which bodies were kept until they showed signs of putrefaction, gained popularity in Europe during the late 1800s. They were essentially hospitals for the dead, their wards of corpses watched over constantly by nurses. In order to mask the smell of rotting human flesh and organs, flower arrangements were placed beside each bed. At the Apparent Dead House in the Netherlands, attendants held feathers and mirrors in front of the corpses’ mouths to check if they were still breathing.

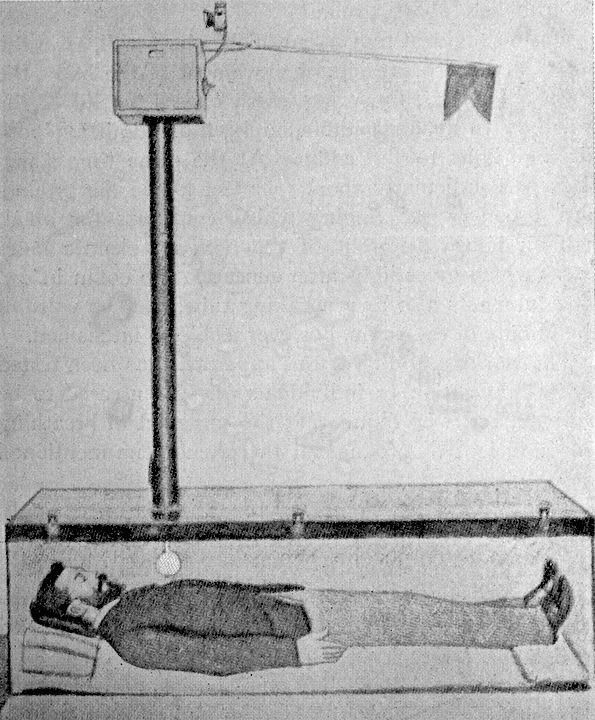

Safety coffins addressed the primal fear of premature burial by incorporating design features such as air tubes, strings linking the body’s hands and feet to an above-ground bell, flag or lights and, for coffins installed in vaults, spring-loaded lids. Despite the rash of patents and production, there are no reported cases of the left-for-dead being saved by such contraptions.

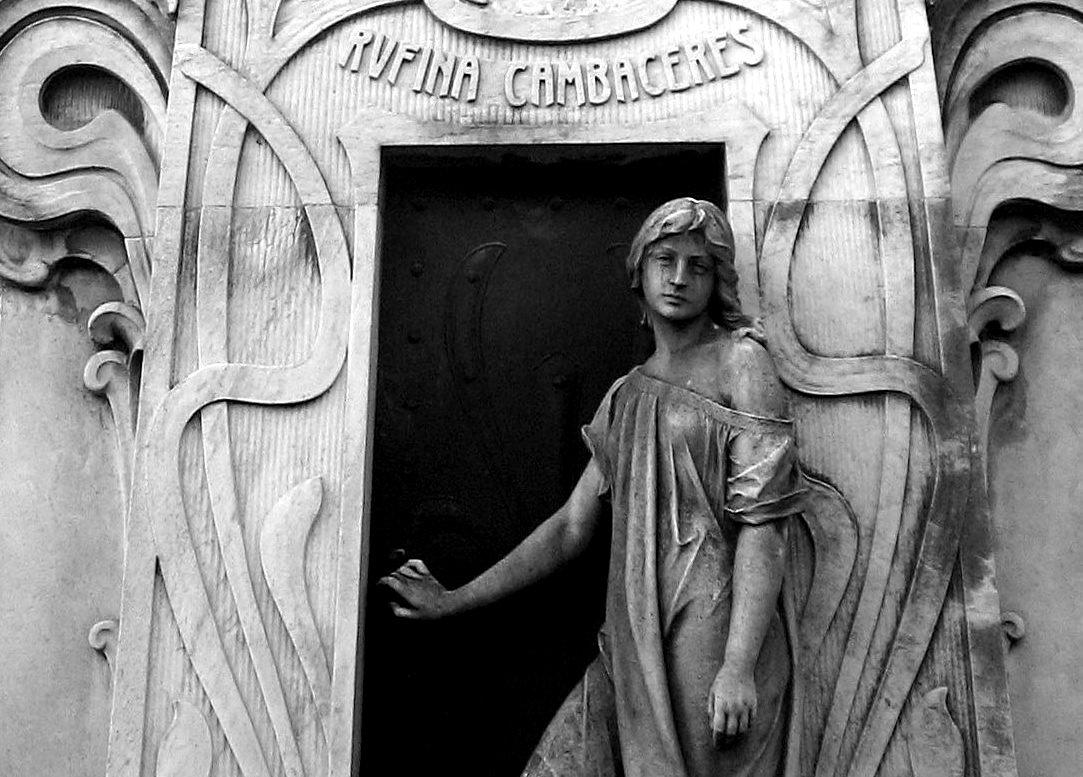

There are, however, several accounts of premature burial, both during the reign of Queen Victoria and beyond. Few are more dramatic than the tale of Rufina Cambaceres, the Argentinian woman known as “the girl who died twice.” The story goes that in 1902, on her nineteenth birthday, Rufina was getting ready for a night out in Buenos Aires when she lost consciousness and collapsed. Three doctors declared her dead, and the young socialite was placed in a coffin, given a funeral, and sealed in a tomb at Recoleta cemetery.

A few days later, according to the legend, a cemetery worker noticed that the coffin had moved. Suspecting a grave robber, he opened the casket and discovered scratch marks on the inside. Rufina had been buried alive, awakened in her tomb, and made an escape attempt, smashing and scratching the door before she died of cardiac arrest.

Like many “buried alive” stories, it is difficult to separate truth from fiction and Rufina’s story is told with varying layers of embellishment. In one version, her initial “death” is caused by the scandalous revelation that her boyfriend had been sleeping with his own mother.

Whether it’s all true or the result of overactive imaginations, Rufina’s tomb is worth visiting for its haunting beauty alone. It features a full-sized statue of the girl gazing out at the cemetery while holding the door to the very mausoleum that entrapped her.

Visit Atlas Obscura for more on safety coffins, vivisepulture, and Rufina Cambaceres.