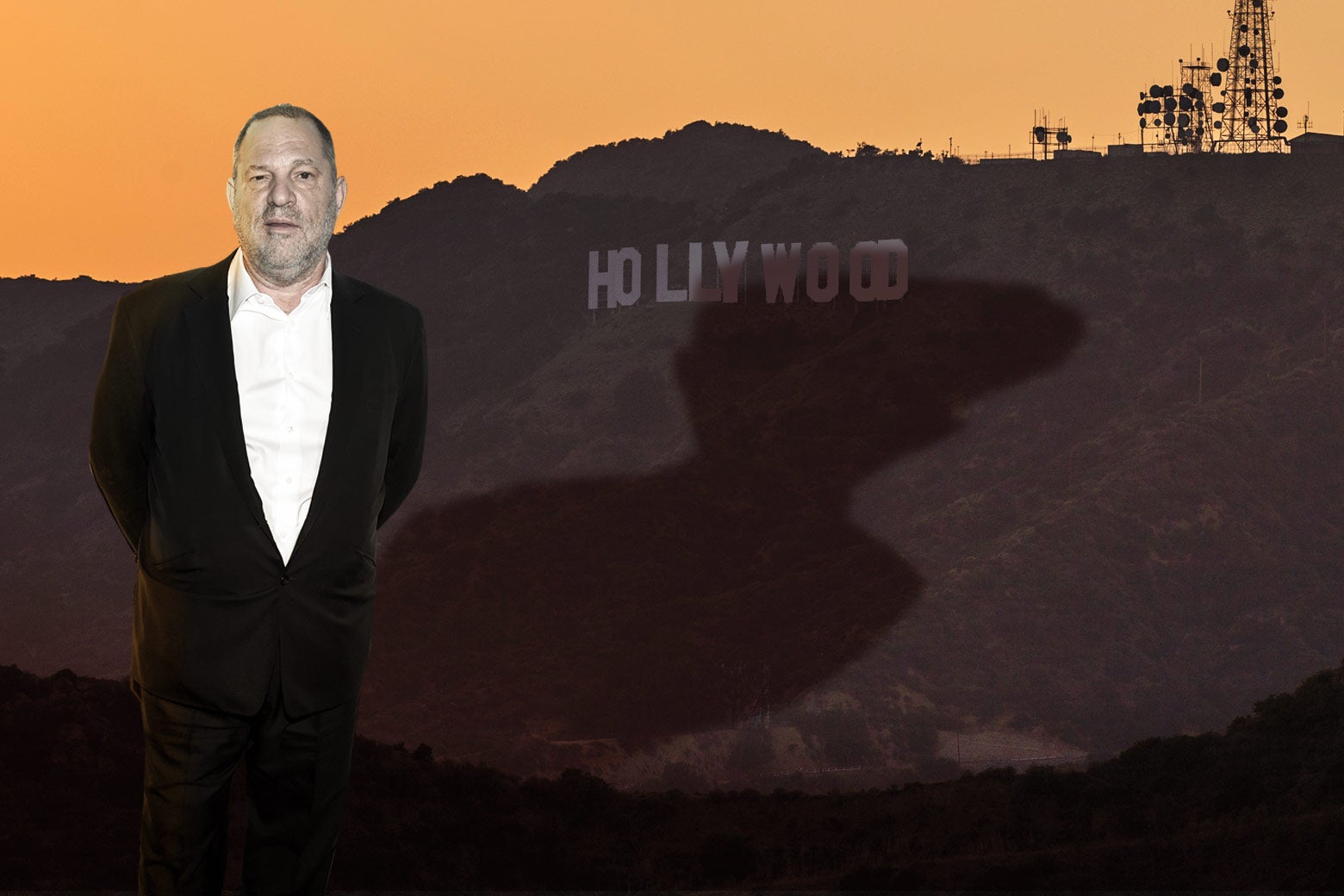

For the past week I’ve been pacing my apartment in a hypomanic state, pretending to get work done while following—probably more closely than anyone who aspires to sanity should—the Harvey Weinstein scandal, with its ever-steepening crescendo of allegations that the fabled indie producer carried on a 30-year side career as a deliberate and ruthless sexual predator. As each new story breaks, the evidence gets starker that Weinstein was in effect using the company he ran with his brother as a personal procurement agency, enabled by a complicit workplace, a sick industry, and a broader ambient culture of misogyny and unchecked male privilege. Our family’s swear jar, which my puritanical 11-year-old insists on monitoring, has been filling up faster than usual. When we can’t fit in any more coins, I’ll donate the haul to an organization that aids abused women—or, perhaps more fittingly for this situation, teaches men not to abuse in the first place. We could use more charities like that.

Experientially, for me at least, and I believe for many women, this week has felt more than anything like a show business–themed reboot of the horrible seven days that followed the election of Donald Trump, almost a year ago now. There’s that same sense of reality shifting to reveal a hidden and perverse order, one that was there all along—we sensed it obliquely, even made jokes about it—but that had never before been put on such blatant, obscene display. I was talking with some women about this yesterday, trying to pin down the precise dimension of the feeling. It’s the sinking realization of the unexpected depth of a problem, the discovery that your kitchen floor doesn’t just need refinishing but has been eaten from within by a seething mass of termites.

On Wednesday’s Slate Culture Gabfest, our weekly podcast about the arts, my co-host Stephen Metcalf asked whether, in the course of a decade of writing on movies, I had encountered any of the more sordid Weinstein rumors. In the weighted word that’s emerged as an ambiguous moral litmus test this week, did I “know”? I truly didn’t—a fact that, even as I recognized it, made me guiltily question whether I should have. If I’d read the trade papers more assiduously, or paid attention to industry gossip, or dug into the subtext of Seth MacFarlane’s joke during the nomination announcements for the 2013 Oscars, I might not have been as blindsided by the disclosure. I’m sure I was watching that early-morning announcement, still bleary from sleep, pen in hand to scribble down notes for a “who was snubbed?” post, mentally fast-forwarding past the joke as another crass Seth MacFarlane moment. And all that time it was my humanity, along with that of half the human race, that was getting the snub big time.

Layered over the conversations about what happened to whom, which are incredible enough—Mira Sorvino? Gwyneth Paltrow? Angelina fricking Jolie? Was no woman in Hollywood powerful enough to be out of this man’s sticky-palmed reach?—are the conversations about who knew what when, or should have, and what actions those who knew or suspected should have taken. These conversations can too easily devolve into blame-shifting, and shouldn’t. Ultimately the responsibility rests with one man. But they’re important conversations, too, in that they acknowledge the systemic nature of the abuse. That’s what makes this serial-abuser story different from that of, say, Bill Cosby: Harvey Weinstein wasn’t just a highly successful individual but the creator and maintainer of a whole production line of success, known for his bullheaded but unstoppable Oscar campaigns, often for films starring and marketed to women (Chocolat, Emma, Shakespeare in Love). It was true that he could make or break an actress’s career, like a cigar-chomping old Hollywood mogul. MGM’s Louis B. Mayer, a patriarchal fosterer of talent to whom Weinstein was often compared, used to make the teenage Judy Garland sit on his lap. Even before he was exposed as a serial abuser and alleged rapist, Weinstein was well-known for trafficking in women. The shock is just in discovering how literal, and how violent, that traffic has been.

The movie industry I’ve known for the past 30 years—and written about for more than a third of that time—is reconstituting itself in my mind this week like pieces of a broken mirror being glued back in place, the cracks now forever visible. Gwyneth Paltrow holding her Oscar for Shakespeare in Love, standing beaming next to the man whose hotel suite she had to escape from a few years earlier after he invited her to the bedroom for a massage. (He laid off after a talking-to from Paltrow’s then-boyfriend Brad Pitt, now also forever to be remembered as someone Who Knew.) Or Mira Sorvino getting her Oscar for Mighty Aphrodite and then mysteriously—or perhaps not so mysteriously anymore—fading from the screen. Or Rosanna Arquette never going on to the career she deserved—maybe she would’ve won her own Oscar, or gone on to direct, or run a studio not based on trading female flesh. Or all the once-aspiring actors like Sophie Dix, whose names I didn’t know but who I might be a fan of today if they hadn’t been scared away from show business by encounters like the one Dix still deems “the single most damaging thing that’s happened in my life.”

Asia Argento, the fiercely original actress and director who’s the daughter of Italian horror maestro Dario Argento, says she lived through her own private horror movie with Weinstein, an experience of forced oral sex that she vividly describes as “a big fat man wanting to eat you … a scary fairy tale.” Her story, as told to Ronan Farrow in the New Yorker—where it’s accompanied by Weinstein’s denial of all “allegations of non-consensual sex” and all “acts of retaliation against any women for refusing his advances”—was particularly courageous both in its explicitness and in its candor; as she tells Farrow, that frightening first encounter later turned into a consensual, if one-sided and power-imbalanced, sexual relationship. In the most wrenching detail of Argento’s account, she describes, that first night at his hotel, faking what Farrow euphemistically calls “enjoyment”—feigning, one supposes, an orgasm—to bring the assault to an end. She says that since that moment, which must have called for a performance beyond all Oscars, she has never been able to take pleasure in that supposedly woman-centered sex act again. If nothing else good comes of this awful week, at least the continuous wave of new stories about abuse and harassment in show business and other industries—Thursday, Amazon suspended one of its top executives after a harassment allegation—makes it clear that women, actors or no, are done pretending.