Every Thanksgiving, we give Instagram so much to be thankful for. “Over 10 million photos that mentioned Thanksgiving-themed words in their captions were shared yesterday,” the disembodied voice of the social network announced in a blog post upon the conclusion of the Thanksgiving holiday in 2012. “For several hours throughout the day, more than 200 photos about Thanksgiving were posted every second.” It was the busiest day the network had ever had. One year later, Instagram users again broke the upload record with their holiday pics. Instagram was “thrilled to see people use Instagram to share their holidays,” the company wrote.

Me, not so much. Thanksgiving is the busiest day on Instagram and also the worst. Social media functions simultaneously as a diary (where we keep track of notable events in our personal lives) and a newsletter (through which we keep our friends and families informed of our movements). But the same material rarely satisfies both ends equally, and the divide is most stark on Thanksgiving Day. It’s natural to want to preserve some memories of a time when far-flung family members come together to prepare and eat a meal. It is unnatural to want to spend the day thumbing through pictures of other people’s stuffing.

Instagram and Thanksgiving may appear perfectly paired—both are obsessed with food. But that’s also why the platform and the holiday don’t complement each other—Thanksgiving didn’t need to be more food-themed than it was before. In her book Food and Social Media, food scholar Signe Rousseau compares food-focused social media to “a perpetual Thanksgiving dinner,” a “virtual table for sharing food and for giving thanks for the people seated around it.”* In both cases, we’re encouraged to gorge, “only realizing we have eaten too much after that last slice of pie.” Rousseau calls this “the paradox of plenty of social media: in order to reap its benefits, you have to take part, and by taking part you risk either exposing yourself to too much of this good thing, and/or contributing to the same.”

Part of the problem is that Thanksgiving traditions are so rooted in the familiar. Instagram is intriguing on Halloween, a holiday about shocking transformations. It’s informative on Christmas, when a social network’s disparate traditions reveal themselves—a Nativity scene juxtaposed with a pagan troll arrangement; a glazed ham followed by a plate of Chinese food. Even standard food Instagramming allows for some element of surprise: What’s for dinner? But on Thanksgiving, conforming to convention is kind of the point. So here’s how it goes down: Yams are vaulted to cultural prominence on Thanksgiving; you feel like you ought to acknowledge your engagement with this significant dish by ‘gramming a photo of it; your friends are subjected to a hundred picture of yams, while themselves eating yams; it’s the worst.

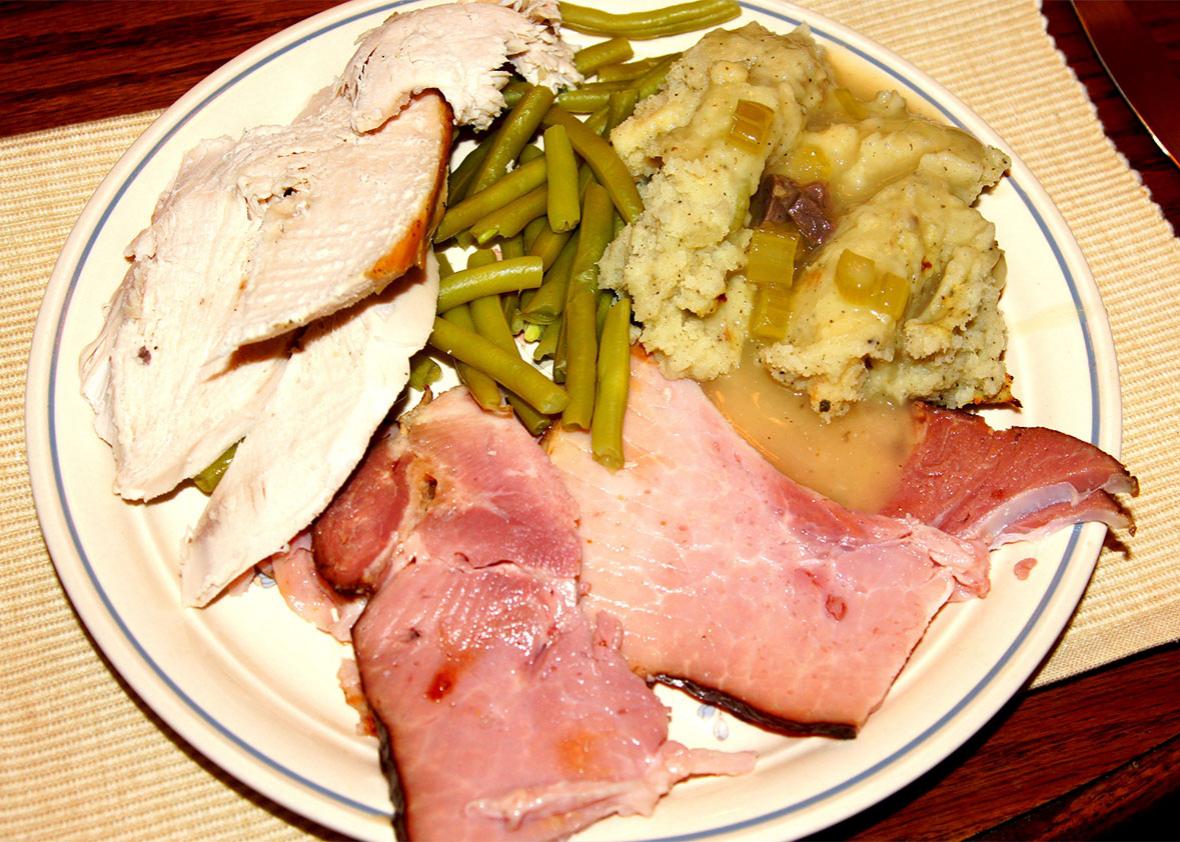

Also, the food looks gross.

The traditional Thanksgiving spread resembles the scene of a medical emergency: vegetable casseroles that appear predigested; starches mashed into shapeless slop; lumpy red gelatin oozing around fleshy cuts of meat. It was made to be consumed, not seen. The main course—a whole bronze bird!—seems visually interesting until you’ve scrolled past every friend’s identical avian carcass, at which point you may begin to feel strangely stuffed. A 2013 study published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology suggests that looking at pictures of food makes the food itself seem less appetizing when it comes time to actually eat. The new Thanksgiving tradition of photographing too much food is messing with the storied Thanksgiving tradition of eating too much of it. Are we prepared to make that sacrifice?

Meanwhile, because everyone’s eating essentially the same thing, the natural inclination to compare oneself to the photographs scrolling by is whipped to new heights. When the New York Times published its inevitable Instagram envy trend piece in 2013, it lead with the horrifying tale of a Philadelphia woman who thumbed over to Instagram that Thanksgiving to share in her social circle’s holiday cheer, only to be affronted by a friend’s insufferable photograph of a “ ‘mashed potato bar’ featuring 15 spud-filled martini glasses artfully arranged in a pyramid, alongside a matching pyramid of bowls of homemade condiments.” When I asked food stylist and author Suzanne Lenzer for some tips on avoiding the various pitfalls of Thanksgiving food photography, she told me: “Eat and drink and talk and laugh and don’t turn on your bloody iPhone for this one day. And give thanks that you have all you do without having to get the validation of an unseen audience to know you’re happy.”

As usual, Black Twitter does it better. The hashtag #ThanksgivingWithBlackFamilies trended early this week as Twitter users paired insights about shared holiday experiences with endlessly iterating reaction GIFs. The result was a roiling communal experience that managed to be familiar without becoming tedious, competitive but not insufferable, seasonal yet not clichéd—everything Thanksgiving Instagram is not.

In her book, Rousseau argues that online food obsession suffers from what cultural historian Neal Gabler calls the “post-idea world.” In this world, writes Gabler, “Few talk ideas. Everyone talks information, usually personal information. Where are you going? What are you doing? Whom are you seeing? These are today’s big questions.” I’d add: “What are you eating?” If your social media documentation of Thanksgiving dinner doesn’t manage to say something new, insightful, or funny, perhaps it was only meant to be shared with those who care so much about you that they’re actually sitting at your table. Unless there’s a dog in your photo trying to eat human food—that is also fine.

Read more Slate pieces about Thanksgiving.

Correction, Nov. 29, 2015: This article originally misidentified Signe Rousseau as a chef and scholar. She is a food scholar, but not a chef. (Return.)