Last year blogger Beejoli Shah started to notice a curious new artifact populating her social media feeds: screenshots of office chats, mostly taking place in an upstart workplace communication tool called Slack. At first Shah failed to see the appeal of sharing a few lines of water cooler conversation among co-workers that, more times than not, appeared basically unintelligible to outsiders. But soon she found herself mesmerized by the look and feel of Slack. As the Slackbrags mounted, Shah, an associate editor at the Frisky, campaigned for her co-workers to get on Slack “solely out of jealousy,” Shah says. “There was a definite sense of missing out not being on Slack. Like, being able to work-chat isn’t enough now. Slack itself has become a character.”

Now, the Frisky is officially a Slack office—just like HBO, eBay, Mint, Venmo, Sony, Nordstroms, Crossfit, Dell, the New York Times, GoDaddy, PayPal, Blue Bottle Coffee, Urban Outfitters, BuzzFeed, Gawker, and Slate. Even pockets of the State Department are now on Slack. The company is currently valued at $2.8 billion. Take a tour of Slack on the company’s website, and you’ll learn about all the ways it can make your office communication more effective: Slack syncs seamlessly across devices, features a powerful internal search engine, and is highly compatible with dozens of other programs that keep businesses running. But Slack’s truly innovative offering goes unlisted: It is a cool office culture, available for instant download.

It used to be that the mark of a “fun” office was a foosball table crammed into the break room. But Slack makes the workspace itself feel like a game. When a new employee joins Slack for the first time, she’s greeted by Slack Bot, a chatterbot who will serve as her simplistic but well-mannered consort in her travels through the app. Instead of asking employees to fill out a traditional profile form, Slack Bot engages the employee in repartee, asking for her name and title and thumbnail photo, all the while showing her how chat works before she tries it with actual humans. When she thanks Slack Bot, Slack Bot replies, “For sure!” And when she clicks into Slack proper, she scrolls down an eggplant lane of bustling public channels (mainly for working), intimate private groups (often for socializing), and one-on-one direct messaging (perfect for bitching). Each of her new colleagues is fitted with a little green dot that says: Go ahead, chat with me!

Slack founder Stewart Butterfield tells me that his “background in game development really helped in designing Slack”—the company started as an internal messaging system for developers of Butterfield’s now-shuttered video game project Glitch—because whether you’re trying to coax users into an immersive online gaming world or immerse them in their job, “you have so little time to attract their attention,” he says. “Every little thing counts.” And Slack is loaded with little things. It’s painted in a prep-school plaid pattern with a jellybean color scheme. Workers can play Jeopardy! in Slack, or host Pokémon battles there. Slack also connects seamlessly with an animated search engine called Giphy; just plug in a keyword (like work) and enjoy a related GIF (like Homer Simpson spinning his office chair around and around in a nuclear power plant). When the CollegeHumor offices first discovered the Giphy feature, late one Friday afternoon, they couldn’t stop summoning GIF after GIF, leading to “the most nonsense traffic jam ever,” says CollegeHumor writer-director Paul Briganti; the company ultimately made its own Giphy channel to prevent the tool from totally derailing actual work threads.

Slack’s mission is to “make your working life simpler, more pleasant and more productive.” It seems best-suited for the second goal on that list. Goofing off on Slack is really fun. The chat system makes it easy for users to create their own inside jokes. CollegeHumor treasures an emoji of a gluten-free duck; Briganti says its meaning is unexplainable to outsiders. Deadspin taunts staff writer Greg Howard with a mock rap CD cover featuring his face and dubbed “Hollywood Howard.” P.J. Vogt and Alex Goldman, co-hosts of the Gimlet Media podcast Reply All, have created little emoji of each other’s faces that they use to further develop their lovingly antagonistic office relationship: Goldman drops a P.J. face in Slack to try to get his attention; Vogt inserts the Alex face to signify “bad news.” Slate favors a custom emoji of Outward editor Bryan Lowder with a toboggan Photoshopped onto his head; when editors drop into a private group to workshop headlines, they announce their presence with a taco emoji. When my friend Thomas, a 28-year-old designer, started work at a tech startup in San Francisco, he found that the office had customized its Slack to execute an elaborate hazing ritual. First, they programmed Slack so that “anytime I said anything, it came out as a GIF,” Thomas says. “Then they set up a bot to tell me I was fired every time I posted.”

Slack’s sway over the dynamics of a workplace is so strong, it’s capable of overpowering the physical design of the actual office. Trendy open-plan offices are infamous for their cacophonous din—they were originally designed to get workers across the office to strike up conversations that hopefully lead to innovative collaborations—but the Slack headquarters are “crazily quiet,” Butterfield says, because all the chatter has moved online. In Slate’s New York office, managers sit in offices around the perimeter while the rank and file linger in the middle; while bosses are free to convene closed-door meetings, it’s hard for underlings to have a private word unless they physically leave the premises. But now, Slack has given every employee a virtual office door, and boy do we use them: Since adopting Slack last year, Slate staffers have exchanged 1.2 million messages, and just 4 percent of them have been aired in the public channels that every employee can see. Seventeen percent of our messages are shared in private groups, which require an invitation to join and are hidden even from administrators; 79 percent of our Slack chatter takes the form of one-on-one direct messages. (Slate thinks its Slack is more open than it actually is. When I asked Slate staffers to guess how many messages are public, answers ranged from 20 percent to 80 percent; that’s a long way from 4 percent. The real numbers are “insane,” Lowder Slacked when he heard them. “Like, what are you all saying to each other all secret-like?”)

Part of Slack’s impressive command over an office’s culture can be explained by how it gets there. Butterfield has said that if he’d launched Slack three years earlier, it wouldn’t have been a success. That’s partly because people who grew up fluent in memes are just mature enough to begin to exert cultural pressure in their offices. Vogt, 29, brought Slack to Gimlet soon after the company launched and is a true believer. (Slack has also advertised on Vogt’s show.) But Vogt’s older boss, Gimlet CEO Alex Blumberg, is still struggling to catch on. “I don’t have much of an emotional connection to Slack,” Blumberg tells me. “I use it to order lunch.” (“I don’t know shit about Slack. Which, I fear, is why you want to interview me,” he emailed when I asked to talk. “Shame on you for mocking an old man in your article!”) It’s only recently that millennials have climbed far enough up the corporate ladder to begin to exert influence over the culture of their offices, but once they did, a communications shake-up was inevitable: A 2012 Pew study found that only 6 percent of teenagers email every day, while 63 percent text daily. “Slack just nailed the user interface at the exact moment when people were finally like, God, fuck email,” says Longform developer Will Mitchell. The week I started at Slate, a friend Gchatted me to ask what it was like. “So many fucking emails,” I chatted back. “All they do is email each other.” Then we got Slack.

Screenshot via Slack

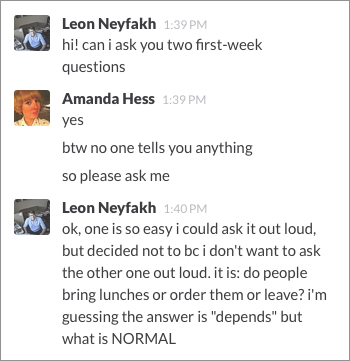

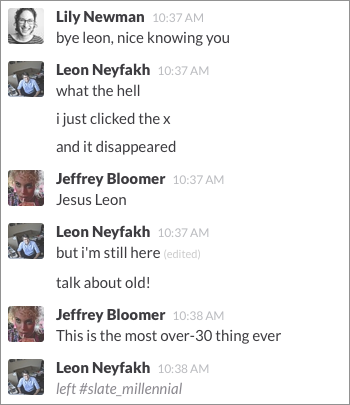

Chatting with your co-workers in the same way you communicate with your friends helps accelerate the office bond: On crime reporter Leon Neyfakh’s first day at Slate, he sent his first Slack to me at 1:39 p.m., and I lasted exactly three hours and 32 minutes before I used the chat to gossip about a mutual acquaintance. (We sit across from each other, and I’d never try the same thing out loud.) Twentysomethings at Slate congregate in a private group where we talk about everything from dating to a topic so sensitive that I am obligated by my loyalty to the group not to mention it here. When a millennial turns 30, she ceremonially exits the group, and Slack Bot is preprogrammed to release a string of emoji in her honor: four volcanoes, five stars, and a skull, so as to suggest a ritualistic volcanic sacrifice. (I’ll get mine in June.) With Slack, founder Butterfield told me, “you don’t need to go to a campground and do trust falls to relate to one another anymore.”

Screenshot via Slack

It may seem counterintuitive, but “there’s a certain intimacy that Slack affords you that face-to-face discussion doesn’t,” says Reply All’s Goldman. “We’ve had very sensitive conversations in Slack when we’re sitting right next to each other.” Slacking someone you’re close enough to actually talk to fosters an instant conspiratorial bond. When Goldman Slacks Vogt, “I can actually watch the response wash across P.J.’s face as he reads it,” he says. “It’s like when you tweet something you’re really particularly proud of, and you watch the page and hope the faves come in.” Slack can become such a lively platform for developing an office bond that it almost feels like the app itself has a pulse. When your colleagues start chatting in a channel, a faint little text line at the bottom of the screen identifies them by name, and when enough people hit the keyboard at the same time, Slack announces that “several people are typing.” It’s a simple phrase, but it signals that the conversation has tapped a collective nerve, and that the thread is about to burst into conflict or cheer. “Sometimes, if a conversation reaches a critical mass in Slack,” CollegeHumor’s Briganti says, “everyone starts talking about it openly. With their mouths.”

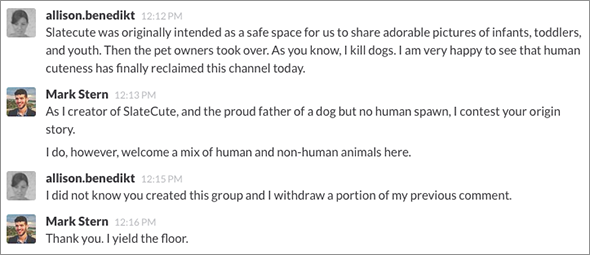

Then, they tweet about it to all their followers. A Slack screenshot functions like a visual snapshot of a company’s particular office culture: They trade in pig uterus GIFs over at BuzzFeed! Turtle-fucking chats at Jezebel! Kid Rock-themed social media puns at the New York Times! Eloping editors at Slate! (Slate editor Dan Kois admits he didn’t ask David Haglund before he blasted his Slacked marriage announcement all over Twitter. Oops.) Doesn’t anyone work anymore?

Screenshot via Slack

Given Slack’s knack for producing procrastination—Slack, it turns out, is not just a clever name—it’s not immediately clear why companies would be eager to get their workers on board. But Slack’s gamification of the workplace functions like a clever trap: Work is so fun, you never want to leave. Slack prides itself on bringing the workplace “wherever you are.” The constant connection fostered by Slack “could be a negative thing,” says Goldman. “But I mean, the show is sort of my life anyway.” At Deadspin, there’s a lull on Slack in the early evening. Once the Deadspin dads put their toddlers to bed at night, Slack picks back up. Just as the Google employee finds herself lingering in the office after traditional work hours—one told the New York Times that she sometimes visits the office on days off, just for the free food—employees outfitted with Slack invariably end up checking in all the time.

Once employees get addicted to Slack, bosses can drop in to track their every move. Deadspin has instituted “a rule called ‘Slack law,’ where if you’re riffing on something for a particular amount of time on Slack, you have to turn that shit into a post,” says Howard. The rule is a smart editorial insight—if Deadspin staffers can’t stop Slacking about something, that’s a pretty good indication that it will be of interest to readers, too—but it also prevents employees from “talking on and on forever, never working, just enjoying each other’s presence.” Slack too much, and Howard worries they’ll “make me blog instead of working on whatever project I’m doing,” so “when I’m actually writing,” he says, “I try to get the fuck out of Slack.” Nothing quiets a boisterous Slack channel like a Slate editor dropping in to ask, “Who can turn this conversation into a piece of content for Slate.com?” Even the bosses at Slack make sure Slack doesn’t get their workers off track. For a while at Slack HQ, whenever a Slack thread inevitably digressed from its stated professional topic, a picture of a mild-mannered baby raccoon would be posted in the thread to remind chatters that they’re “having a conversation that’s best had in another channel.” But now, the company has set up a bot with a raccoon avatar that can be anonymously summoned whenever employees digress.

Screenshot via Slack

Slack allows administrators to monitor how much time their employees are spending on Slack, but the site warns bosses not to read too much into the data: “[S]omeone might be not using Slack for several hours during the day because they are goofing off. On the other hand, they might be away from Slack because they are concentrating very hard on the work that you want them to do,” the app notes. Similarly, appearing available on Slack can either mean that you’re signed in and ready to work, or else swimming in Aruba (“working from home”) with your phone connected as cover. At this point, the sight of employees riffing off-topic on Slack may just be the best indication you can get that they’re actually committed to doing their work. After all, if employees aren’t procrastinating in their office Slack, they’ll find someplace else to do it—like in a Slack of their own making.

Slack has proved itself such a fun place to do business that its users have started launching Slacks for pleasure, populated by strangers and friends; you can join a whiskey Slack, a techno Slack, a Slack for sharing PDFs of journal articles, even a Slack for people who moderate other Slack groups. Vogt is a member of a semisecret social Slack that he keeps running alongside his official Gimlet account. “Every new communication tool looks like a jump rope when you first get it, before you find out it’s a leash,” Vogt admits. Someday, “we’ll all realize we’re wearing party hats on the factory line. But for now, at least, Slack still feels fun.”