For more than a decade, Google has been giving us what we want before we can put it into words. Google’s Autocomplete feature, which first debuted in 2004, is now so ubiquitous among Internet users that it seems redundant to even explain it—just Google it—but here’s the one-sentence tutorial for the Ask.com holdouts of the world: If you enter “blonde” into Google’s search bar, it will instantly serve up predictions of what you might be searching for—the band Blonde Redhead, perhaps, or a recipe for blonde brownies, or information on a newly blonde Kim Kardashian. As popular interests shift, Google recalibrates and ushers in new suggestions.

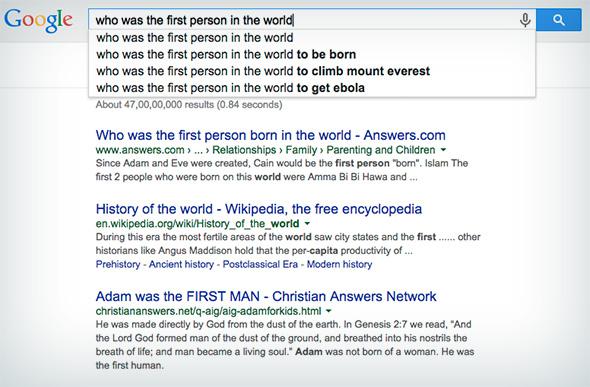

A couple of years ago, a young television writer’s assistant named Justin Hook had the idea to turn Autocomplete into an online guessing game in the style of Family Feud. Google Feud offers up the beginning of a Web search, then challenges players to guess Google’s top 10 suggested autocompletes. Unlike the syndicated game show, where contestants are generally rewarded for guessing the most sensible answers to survey questions, Google Feud’s answers are unexpected, odd, and sometimes perverse. “People found it kind of frustrating at first, because a lot of the answers are impossible to guess,” Hook says. In fact, the game’s subversive appeal is heightened when players fail: Type in a reasonable guess, and you’ll likely be confronted with the much weirder “correct” answer. One stage, for example, asks players to guess the top 10 Google autocompletes for “who was the first person in the world to.” One of the top responses Google spits back is “fart.”

Screenshot via Google

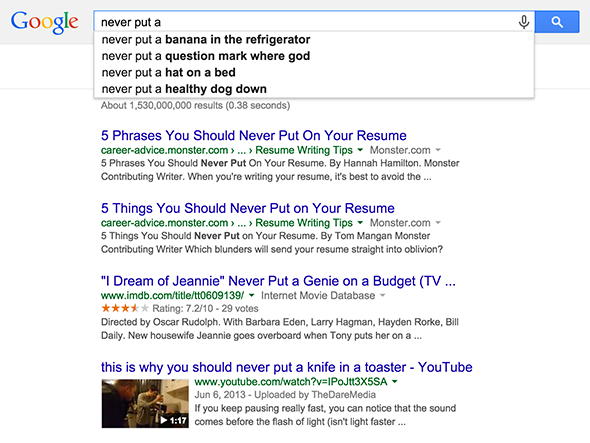

Google sells its Autocomplete feature as strictly practical. The company’s Autocomplete FAQ says that it was designed to save time (people read faster than they type) and correct spelling mistakes (spelling is hard). In 2010, Google advanced its Autocomplete functionality with Google Instant, a feature that not only predicts what you’re searching for, but also fetches the actual page results in real-time—no need to finish your thought or bother to hit the “search” button.

Google claims that Instant can save users two to five seconds per search; add up all the Google searches launched around the world, and the feature saves the global population “more than 3.5 billion seconds a day.”

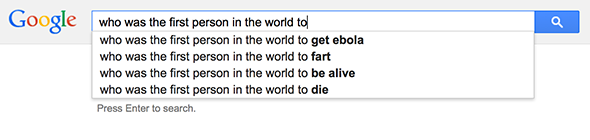

Screenshot via Google

Despite all its claims of efficiency, I often find myself lingering on Google’s Autocomplete drop-down menu. If you key in the right prompt, Google will finish your sentence with something so weird (“can i vacuum … my dog”), conspiratorial (“what really happened to … the dinosaurs”), or even profound (“what if google … never existed”) that it’s impossible to click away. Google is a massive technology company that operates through opaque algorithms, but Autocomplete produces the illusion that there is some human element rising up from inside the machine—a whole English-speaking hive mind, even.

In a study published in the journal New Media & Society last year, researchers Esteve Sanz and Juraj Stančík found that people who use search engines the most also express a greater amount of trust in other people; Danish people in particular register as highly trustworthy and search-happy. The researchers theorized that people use search engines not just as a rote information retrieval tool, but also as an avenue for expressing “rising existential anxieties for the self.” People around the world tend to turn to search engines in times of crisis—search activity spikes during tsunamis and coups—but perhaps they also turn to Google in times of personal turmoil, which might explain why so many autocompletes are so dark. (Some of the current top autocompletes for “why is my” include “period late,” “hair falling out,” and “eye twitching.”) Questions too pressing or sensitive for our Gchat friends get plugged into Google instead.

Autocomplete has also produced a new form of ego surfing, beyond the Google alert—searching for your own name to see how Google autocompletes the query in order to glean some intel on how others perceive you. (Or is this just me?) I once heard a group of male writers express jealousy of a friend when they discovered that “girlfriend” automatically popped up after his name—a sign that many women were Googling to discern his availability. Autocomplete can signal professional status, too: The Google autocompletes for “justin hook” are dominated by a 1984 homicide victim (“justin hook jr”) and a male fitness model (“justin hook under armour”), but a while ago, a new autocomplete popped up to signal that enough searchers were looking specifically for the Google Feud creator Justin Hook: “justin hook bob’s burgers,” referring to the TV show he currently works on.

Autocomplete is also a useful tool for eavesdropping on other people’s anxieties. Searching is a voyeuristic bid to “access the ‘consciousness’ of the other,” Sanz and Stančík write, but it’s also a self-conscious attempt to establish a sense of your own place “in relation to the collectivity.” Autocomplete instantly tells us what other people are thinking, and where we fit in. “Our social groups on Twitter and Facebook can be so insular, but Autocomplete feels like a good barometer of what average people are thinking,” Hook says. And unlike on social networks, where we all police each other’s speech, Autocomplete offers an unfiltered look at our fellow citizens’ most unmentionable thoughts. The now-defunct Comedy Central show The Jeselnik Offensive used to feature a segment called “Search and Destroy,” where audience members were asked to guess how Google autocompletes conspicuous phrases like “black people smell like” and “white people smell like.” In 2013, UN Women launched an ad campaign showing how Google autocompletes the phrase “women shouldn’t.” Suggestions included “preach,” “drive,” and “go to business school.”

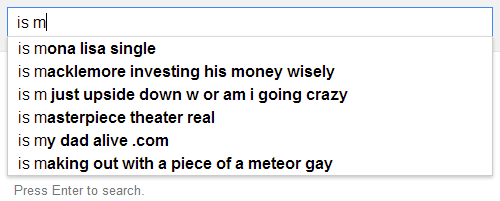

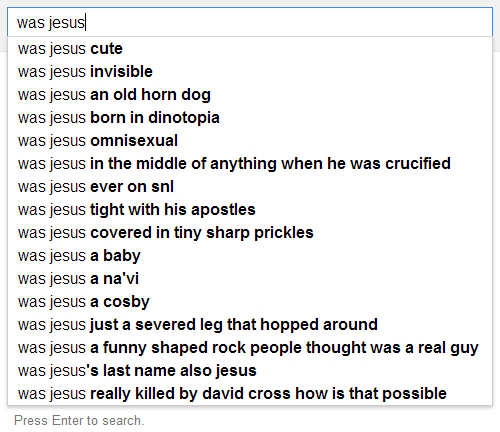

Image by Neil Cicierega

There is a limit, however, to Autocomplete’s ability to honestly reflect other people’s curiosities and insecurities; after all, Google is ultimately pulling the strings. (High-ranking autocompletes for “google is” are “skynet,” “god,” and “your friend.”) A Google spokesperson wouldn’t tell me exactly how the thing works, just that Autocomplete results are “produced automatically based on a number of factors including the popularity of search terms.” Hmm. The inscrutability of Autocomplete lends a dystopian vibe to the search, but that can make it an even more delicious time-suck. “I’ve always gotten a weird feeling from Autocomplete,” says Neil Cicierega, a musician, comedian, actor and web artist. “But I thought I could one-up the weirdness.” In 2013, Cicierega mocked up a dummy HTML page that mimics Google.com, and started populating a joke-art Tumblr called Google Suggest with made-up autocompletes that heighten the capricious and sinister attributes of the ghost in the machine. In one of his bizarre fake searches, a Googler types in “salons in dallas t” and Google autocompletes with: “arnold schwarzenegger swallowing a baby pig.”

When Autocomplete first debuted (as a Google Labs project called “Google Suggest”) Google was eager to promote the whimsical possibilities of Autocomplete. “We’ve found that Google Suggest not only makes it easier to type in your favorite searches (let’s face it—we’re all a little lazy), but also gives you a playground to explore what others are searching about, and learn about things you haven’t dreamt of,” the company said in its initial announcement. “Go ahead, give it a spin.” Like the search engine’s “I’m Feeling Lucky” button—which whisks searchers to a random page in their results—Autocomplete was framed as fun, and maybe a little illicit. This adult “playground” explicitly invited searchers to act as digital peeping Toms, peeking in on what “others are searching about.”

But since then, Google has slowly closed Autocomplete’s window on the world. After Google Instant debuted in 2010, the number of instantly accessible Autocomplete suggestions shrank from 10 to four; searchers now have to futz with their Google settings to see the full list. Google offers an online form for users to report “offensive Autocomplete predictions,” and the company promises to censor “a narrow class of search queries related to pornography, violence, hate speech, and copyright infringement.” A crowdsourced, online “Google Blacklist” of words that Google now refuses to autocomplete includes “ball licking,” “dildo,” and “hot chick.” Foot fetishists eager for images of barefoot celebrity women will find that Google has shut down their favorite colocation entirely; now, when you type in “ariana grande fee,” Google refuses to complete the phrase with the obvious T.

Image by Neil Cicierega

As Google cleans up, it will take increasingly dedicated Autocomplete detectives to discover the remaining weird corners of web search. Stumbling across a notable autocomplete in 2015 feels a bit like punching in a secret code: If you type in the right combination of words, a delightful message bubbles up from the void. Cicierega’s new favorite prompt is “how might one,” because the construction is so stiff that it has to produce results suggestive of a bizarrely prickly personality. Right now you get “how might one implement a playday” and “how might one correct the pH of a lake.” Not exactly useful, which is what makes it so great.