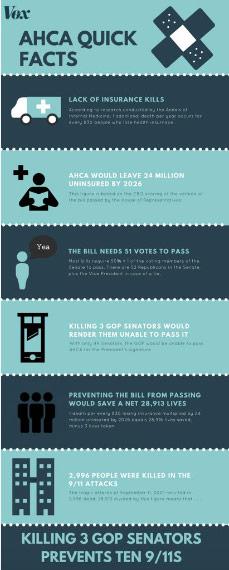

Something weird happened on the wonk internet last week. Shortly after the shooting of House Majority Whip Steve Scalise and others in Alexandria, Virginia, an infographic with the logo of explanatory news site Vox began ricocheting across Twitter. It had the look of something Vox would produce, and it was tweeted by Twitter user @DudeSlater, whose bio identified him as Vox’s editor in chief. But using a bit of Vox-y math, the infographic, titled “AHCA Quick Facts,” came to a rather un-Vox-y conclusion: “Killing 3 GOP senators prevents ten 9/11s.”

Screenshot/Twitter

Meanwhile, another Twitter user also claiming in his profile to be a Vox staffer, @BigMeanInternet, tweeted, “If the shooter has a serious health condition then is taking potshots at the GOP house leadership considered self defense?” Vox quickly denied any affiliation with both users. In reply to @DudeSlater’s post, the site tweeted, “This is not a Vox graphic and you are not an employee of Vox. Please delete this tweet immediately and remove our handle from your bios.” Both users have since removed any mention of the site from their bios as well as the offending tweets. As Ezra Klein, Vox’s actual editor in chief, tweeted in response to Federalist publisher Ben Domenech after Domenech took exception to @BigMeanInternet’s tweet:

“Very weird thing” is right. But Domenech asked a good question: What the hell? To tweak Vox’s tagline, let’s understand the fake news.

On Friday, I corresponded with @DudeSlater via Twitter, where he confirmed that, no, he is not an employee of Vox: “The only real affiliation I have with Vox is the tweets they sent saying I have no affiliation with Vox.” He told me his real name is Alexander Cohen and that he lives in Chicago, where he works in the life insurance industry. He has about 2,000 followers on Twitter, half of whom sprung up after he posted the fake infographic. He told me he stopped posing as a Vox employee after the site demanded he do so and also said he has never met or communicated with @BigMeanInternet but had seen his tweet.

Cohen also told me that he didn’t create the graphic himself and that its creator, whom he would identify only as a resident of Philadelphia, sent it to him, though they don’t know each other personally. He called the infographic, which later bubbled up on 4chan, Reddit, and other users’ Twitter accounts, a “parody” in a tweet. “If this does raise awareness of the AHCA’s consequences, then I would regard it as a positive development,” he later told me. “However the purposes of these actions were strictly for entertainment. I did not foresee it reaching many people who would not understand it was a joke.” (The “sentiment” behind the graphic was “obviously horrific and despicable,” Vice wrote at the time, “but it was also obviously a (very dark) joke” and “no one … really ever believed this was authentic Vox content.”) “I’m not a regular reader of Vox, but I’m aware of their brand,” Cohen said. Politically, he describes himself as “independent left-leaning”; he wrote in “Tim Raines for Hall of Fame” on his 2016 presidential election ballot but says he would have voted for Hillary Clinton to “block” Donald Trump had he lived in a swing state. He also told me he was aware of @BigMeanInternet claiming contemporaneous affiliation with Vox but that the two have never been in contact. “I may have underestimated the credibility that some people would give to Big Hog Calhoun,” he said, referring to the name he lists on his Twitter profile.

@BigMeanInternet, an author whose real name is Malcolm Harris, is better-known. He wrote an opinion piece earlier this month in the Washington Post riffing on his forthcoming book and contributes frequently to the New Republic, which identifies him as “a writer and an editor at The New Inquiry,” the online literary-left magazine. Replying to the Vox tweet denying any affiliation with him, Harris tweeted from his verified account, “woah, sorry about that folks! obvi a typo, fixed now.” I reached out by email on Friday to ask him about the apparent impersonation. “I think I’m going to stick with ‘No comment’ for now,” he wrote.

Harris’ tweeting has gotten him in trouble before. In 2012, he was sentenced to six days of community service after pleading guilty to a disorderly conduct charge associated with a 2011 Occupy Wall Street march in which protesters clashed with police, the New York Times reported. The evidence proving he’d deliberately disobeyed police orders came from a series of contemporaneous tweets, supplied by Twitter under court order, which contradicted his defense lawyers’ version of events.

And what about Twitter’s role in the whole episode? A spokesman for the social media company told me via email that it doesn’t comment on specific incidents involving individual accounts “for privacy and security reasons.” But he referred me to the company’s impersonation policy, which states that “Twitter accounts portraying another person in a confusing or deceptive manner may be permanently suspended under the Twitter impersonation policy.” The site lists “an account is pretending to be or represent my company, brand, or organization” as one of several reportable offenses. Neither Harris nor Cohen were contacted by Twitter about their claims.

Despite repeated inquiries, the company representative wouldn’t tell me how often this sort of impersonation happens or whether Twitter keeps tabs on imposter accounts. A Vox Media spokesperson confirmed to Snopes that, “We have alerted Twitter executives to this issue, and are working with them to have this false information removed immediately.”

The ability to masquerade as other users has long been a problem for Twitter. As JoBeth McDaniel (who picked up a Twitter imposter in 2014) noted in the Daily Beast, “Twitter is jam-packed with fake accounts.” Unlike parody accounts—like @ProfJeffJarvis, which skewered tech theorist Jeff Jarvis until 2016, and a panoply of parodic takes on @realDonaldTrump—fake accounts traffic in deception rather than satire, which violates Twitter’s usage policy. Celebrities like Bill Murray, Will Ferrell, Amy Poehler, Tina Fey, and Jon Stewart all have imposters. But journalists, whose use of the platform to spread information depends at some level on them being who they say they are, are particular targets. Cale Guthrie Weissman, now a reporter at Fast Company, documented the process of shedding his own Twitter doppelganger in a 2015 Business Insider post:

Twitter, in its automated form, asked what sorts of abuse I was facing. I deemed it harassment and impersonation. The form then asked if it used my pictures, how the account claimed to be me, and for each of these instances required that I submit a URL of tweets perpetrating these allegations. …

Once filled out, I received an automated response saying Twitter needed proof of my identity. Using another of its automated forms, I snapped a picture of my driver’s license and uploaded it to Twitter. I then sent a series of tweets, linking to Twitter Support, letting them know what had transpired.

The fake account disappeared after two days, Weissman wrote.

One thing that hasn’t gone away, though, is the question of how exactly we should understand Harris, Cohen, and the like. In some ways they’re fitting emblems of how the Trump era has torqued both the form and intent of online political humor. Viewed on their own terms, the tweets might fall safely within the boundary of satire. As jokes, they might even be considered grimly incisive, turning around the life-or-death stakes of health care reform on the reformers themselves.

But whatever the intent behind them, Harris and Cohen’s claims of employment by Vox were another matter. Dubious sourcing and questionable content have long been mainstays of fake news. Harris and Cohen’s behavior chimed with another faux-news tradition, one that doesn’t just aim to churn out bogus information but, in adopting reputable-looking URLs like BostonTribune.com and ABCNews.com.co or impersonating journalists employed by otherwise-credible outlets, seeks to sow doubt and confusion among readers toward news organizations dedicated to disseminating accurate information as well. Harris and Cohen’s fake credentials undermine journalistic credibility, junk Vox’s reputation, and embolden broad-brush cries of “fake news” aimed at the mainstream media.

They also serve up a buffet of red meat for critics of liberal voices to sample from. Harris and Cohen’s tweets landed like ready-made chum in the conservative media waters. Posts from the Daily Caller, the Daily Wire, FrontPage Magazine, and the Gateway Pundit excoriated Harris’ tweets and played up his alleged association with Vox. Although all four outlets noted that the liberal site disputed Harris’ claim of affiliation—the Gateway Pundit went as far as to say he “lied” about working for the online publication—Harris’ other affiliations weren’t as falsifiable. “This is the left’s hate matrix in action,” concluded FrontPage. “And it’s part of the reason why the shootings happened.”

All of which is to say: If you like a heavy dose of parody in your Twitter feed, the whole episode amounts to something of an internet tragedy. The lesson seems to be that any humor that isn’t plainly labeled as such risks spreading misinformation or serving as partisan ammo. (And it goes without saying that any humor that is plainly labeled is probably less fun.)

When I wondered whether he regretted posting content that could be construed as a call for violence against Republicans, Cohen demurred. “I think the danger of violence being incited from jokes on the internet is relatively low compared to the danger of violence being incited from people learning how they will be affected by policy,” he said. “If conservatives are actually arguing that, it feels wildly hypocritical given their defense of the current rise in hateful rhetoric and incitement of violence against people for their identity (race, religion, gender) as falling under the purview of free speech.”

I asked Cohen how he thinks about his own online presence in relation to his decision to post the infographic. Is he a provocateur? A run-of-the-mill Twitter troll? A graveyard-humor satirist? A health care activist? Someone who really wants to land a job at Vox?

“I’d say my account is dedicated to baseball and politics,” he replied.