Want to change the channel on your Apple TV? Tap your iPhone.

Need to unlock to your Mac? Use your Apple Watch.

Feel like buying something online? Touch your iPhone’s fingerprint sensor to make the purchase through Apple Pay.

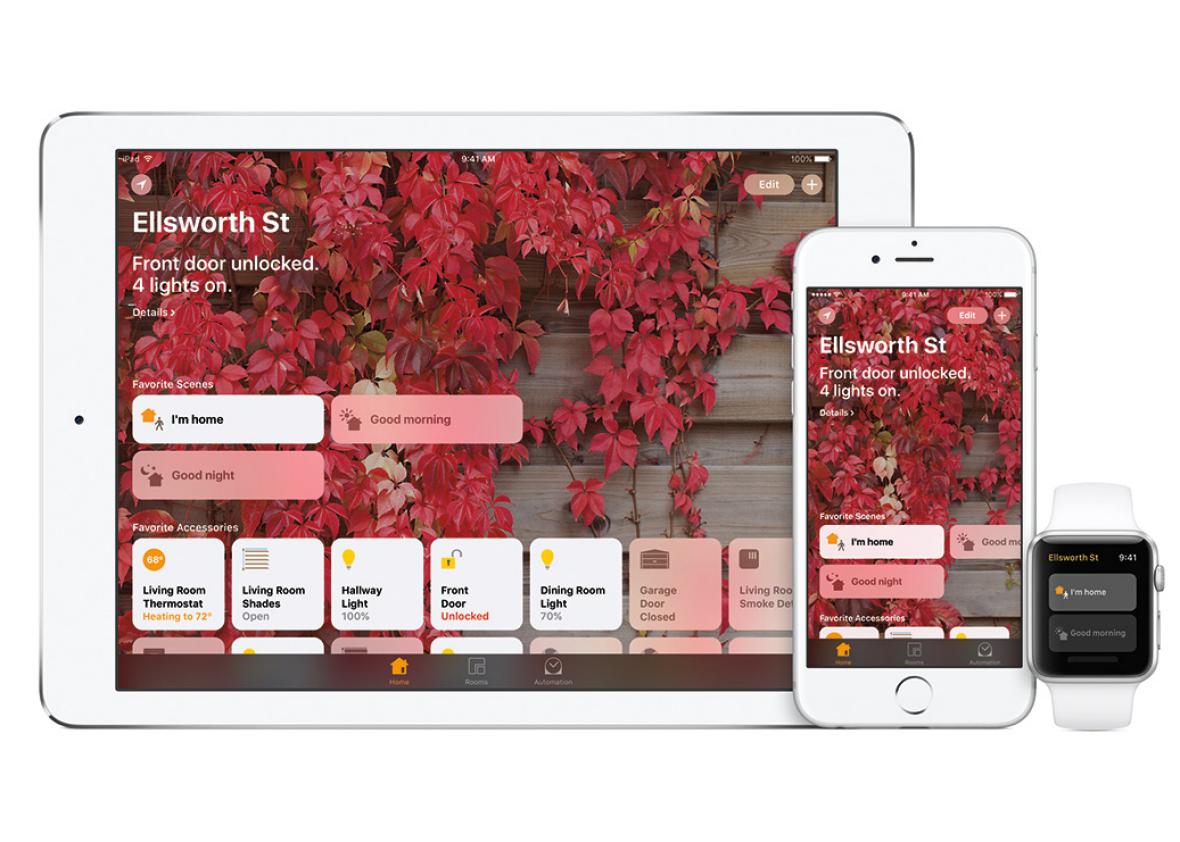

Forgot to lock the doors, turn off the lights, or turn on a security camera? Talk to Siri on your Apple TV. Or, if you’re away from your house, use the new “Home” app on your iPhone, and it will relay the message to your Apple TV. Oh, and if you want to ask your Mac to open a file or play music, you can now do that with Siri, too.

You can do a lot more with iMessage now, too, but as my colleague Lily Hay Newman pointed out, there’s one big thing you still can’t do: Use it on an Android device.

Among the seemingly endless string of software announcements at Apple’s annual Worldwide Developer Conference on Monday, this was a recurrent theme: The more Apple devices you use, the better they’ll all work together, and the more seamlessly connected your online life will become. Apple devices beget Apple devices, and the company’s cloud software is the common language that binds the whole family—and shuts other companies’ devices out.

This approach to hardware and software design, which prioritizes continuity among a single company’s proprietary systems over openness and interoperability, is not new, nor is it unique to Apple. But it has been a hallmark of Apple’s strategy from the beginning, thanks to co-founder Steve Jobs. And this week, Tim Cook and company took it to a new level.

All five of Apple’s core devices—iPhone, iPad, Mac, Apple Watch, and Apple TV—now speak with the same voice: Siri’s. With the renaming of OS X to macOS, their operating systems now share matching nomenclature: iOS, macOS, watchOS, and tvOS. Even the company’s apps and services are converging, with everything from Apple Music to Apple Pay to Photos to iMessage crossing the bridge from mobile to desktop in the past year or two.

This convergence has been underway for a while at Apple, as it has elsewhere. Many of the continuity features that Apple unveiled Monday are echoes of the offerings on Google Android and Chrome OS devices. Likewise, Amazon’s Echo and Fire TV were already doing some of the things that the Apple TV will do now. And Microsoft has leapfrogged Apple in some respects by unifying its mobile and desktop operating systems, although that’s less of a challenge when you have a relatively small number of mobile users.

Apple

What became clear Monday is that Apple isn’t simply playing catch-up. As in other realms where it was not the first mover, Apple is positioning itself for the long game. In this case, the objective is to control the software that runs everything from your computing devices to your television to your household appliances—and, eventually, your car.

For Apple, these moves to consolidate power and fortify the walls of its tech empire come at a pivotal time.

I’ve argued that we’ve already seen peak Apple—the apex of its dominance—and that the company’s incredible run at the top of the technology industry is in jeopardy. There are a number of reasons for that, but the foremost is that Apple’s pre-eminence was built on a device—the iPhone—that feels less exciting with each new iteration, and whose success the company has been unable to replicate with follow-ups such as the iPad, Apple Watch, and Apple TV.

Another threat comes from the realm of artificial intelligence, which Google and Facebook are vying to dominate, and which does not play to Apple’s strengths as a company or corporate culture. Apple’s secretive, hierarchical structure has proven itself conducive to designing beautiful, perfectly self-contained products. But it’s inimical to the culture of academic freedom, openness, and experimentation that pervades the field of artificial intelligence, and it may be preventing the company from hiring top minds like Google’s Demis Hassabis or Facebook’s Yann Lecun. Even Microsoft and IBM may have an advantage over Cupertino when it comes to building the algorithms that will animate the 21st century.

Another obstacle may be Apple’s growing emphasis on privacy. On Monday, the company pledged that the machine-learning software in iOS 10 will process your data locally, on your phone, to avoid sending it to the cloud. That sounds like a great security feature, but one that could limit the scope and inhibit the development of the company’s deep learning algorithms.

Apple isn’t going to just give up, of course. The company will try its best to make Siri as versatile as Google Assistant, iMessage as futuristic as Facebook Messenger, and the Apple Car as safe as any self-driving Google, Uber, or Tesla vehicle. To the extent that virtual assistants are the new platform, improving Siri and opening it to new applications should be especially high on the company’s list. Apple took a step in the right direction on Monday with the announcement that Siri will now be available to certain types of third-party apps, albeit far fewer than already have access to Google Now and Amazon’s Alexa.

In the meantime, Apple can keep its rivals at bay by leveraging the greatest advantage it enjoys today: its leading position across multiple consumer-device categories. Amazon may have a nifty set-top TV box—but if you already have an iPhone, you might prefer the Apple TV. Google’s virtual assistant software may be more powerful than Siri—but if Siri already lives on three of your devices, why switch to Google when it’s time to buy a fourth? Skype might have its advantages over FaceTime, but your grandmother has the latter pre-installed on her iPad. In other words, Apple can prop up its software by putting it front and center on all the platforms it already has, and making sure they all talk to each other—and no one else.