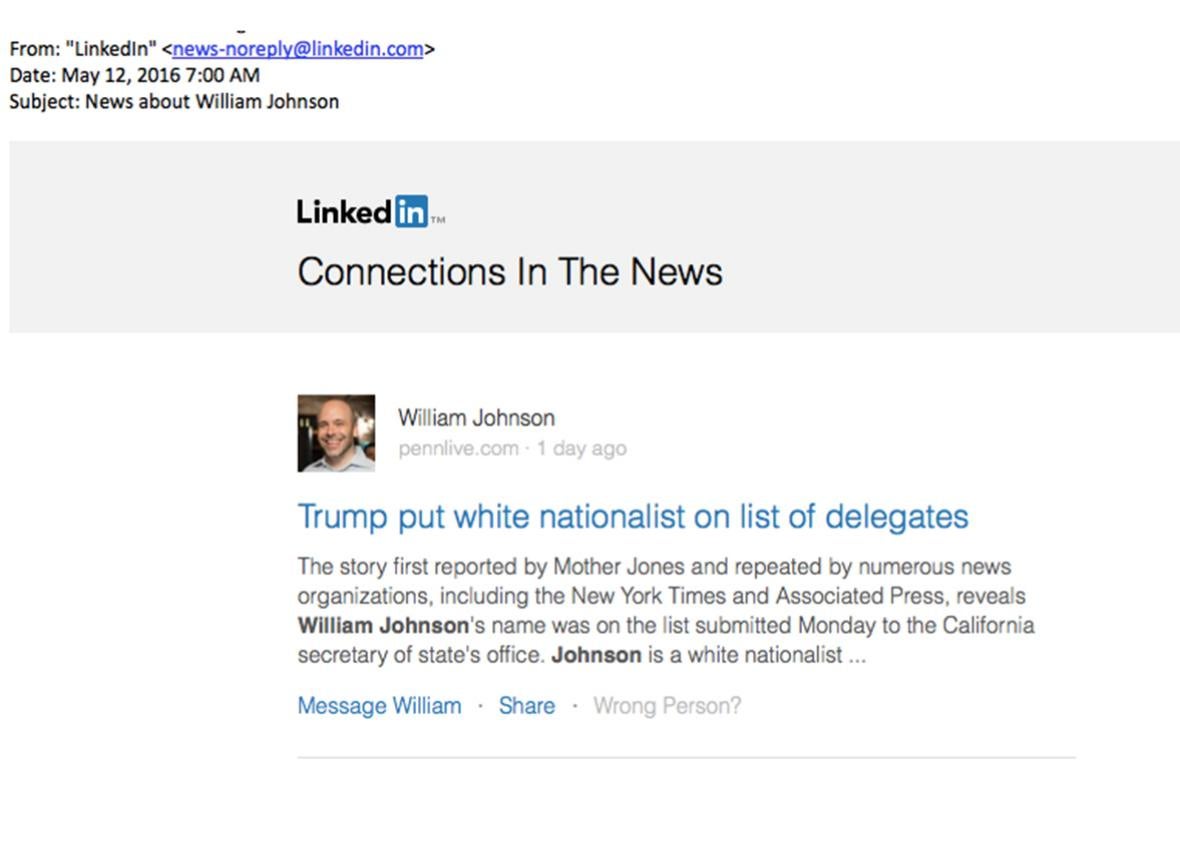

On the morning of May 12, LinkedIn, the networking site devoted to making professionals “more productive and successful,” emailed scores of my contacts and told them I’m a professional racist. It was one of those updates that LinkedIn regularly sends its users, algorithmically assembled missives about their connections’ appearances in the media. This one had the innocent-sounding subject, “News About William Johnson,” but once my connections clicked in, they saw a small photo of my grinning face, right above the headline “Trump put white nationalist on list of delegates.”

This surely caused a few of my professional acquaintances to spit-take. I’m a middle-school teacher in New York City. I am not a white nationalist, nor have I been on the list of delegates for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. But I share a name with someone who can claim those two traits.

I emailed LinkedIn and requested that the company somehow issue a correction to my connections, making it clear that I’m not, in fact, the William Johnson who has proposed revoking the citizenship of and deporting all people of color living in the United States. My email included the words libel and attorney, so I hoped for a quick response. It was 8:44 a.m. I had to go teach my eighth-graders.

Two hours later, LinkedIn had yet to respond, so I sent another note. At this point, I’d received a bunch of messages from confused connections. It turns out that when LinkedIn sends these update emails, people actually read them. So I was getting upset. Not only am I not a Nazi, I’m a Jewish socialist with family members who were imprisoned in concentration camps during World War II. Why was LinkedIn trolling me?

Soon I found myself reading up on the other William Johnson. He is a chair of the American Freedom Party, which advocates defending the “core European American population” from “the immigration invasion.” The party’s website features grim-faced members holding signs that read “diversity = white genocide” and “white lives matter.” According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, Johnson is an apparent disciple of Mein Kampf who has attended Holocaust denial conferences. This May, he was selected as a delegate from California supporting Donald Trump’s nomination at the Republican National Convention; he stepped down from the appointment soon after to avoid weighing down Trump’s campaign with his “baggage.” Suddenly, I was less concerned about LinkedIn’s customer service—two days later, the company still hadn’t responded to my complaint—and more concerned over why it was updating anyone about this man’s professional developments.

After all, if LinkedIn’s algorithms had functioned properly, what would have happened? Would the company have emailed an actual white supremacist’s professional contacts to inform them about these exciting happenings in his career? The racist LinkedIn community would have been abuzz. Did you hear about William? I just endorsed him for his skills at “praising Nazis” and “terrorizing immigrants”!

As it turns out, LinkedIn doesn’t even pretend its “Connections in the News” feature is reliable. There’s a disclaimer at the bottom of the emails, in very small print, that reads, “LinkedIn does not guarantee that news articles are accurate or about the correct person.” And the LinkedIn site sheepishly acknowledges that its “Mentioned in the News” emails are generated by an algorithm that is “not perfect.” It even requests that members check the identities of people named in their emails and “please report” any errors.

In other words, LinkedIn has recognized the possibility of these types of errors and realized its product isn’t sophisticated enough to avoid them. Yet it still sends “Connections in the News” emails, relying on the (unpaid) assistance of consumers to compensate for its blind spots. You don’t have to have been mislabeled a white supremacist for that approach to feel arrogant. It’s similar to the arrogance of Dropbox and Airbnb employees booting neighborhood residents off a soccer field they’ve used for years. It’s the arrogance of Yammer CEO David Sacks’ lavish “Let Them Eat Cake”–themed birthday party.* And it’s the arrogance that led Airbnb to run a series of citywide ads negging San Francisco’s public schools and libraries after the billion-dollar short-term rental company had to pay its taxes. With LinkedIn, specifically, it’s the arrogance of sticking with a product that might easily, say, tell your contacts that someone with your name is dead.

A full five days after I made my original complaint, the company’s “Trust and Safety” department finally responded. At that point, my connections had stopped emailing me about the white nationalism story. The company offered to send a tepid correction to my contacts, explaining that the article was “about another person.” I asked that they change the wording of the correction to make it clear I find white nationalism and white supremacy abhorrent, and, a couple of days later, they agreed. The corrective email was sent. The issue was resolved.

The nature of profit is that you take more than you give, so it’s not surprising that these billion-dollar behemoths that call themselves startups take far more from us than we get in return. That transaction has become even more severe thanks to companies like LinkedIn (and Google and Facebook), which offer consumers free services and then sell their data as the product. LinkedIn accidentally called me a white supremacist. It didn’t cost me much, but a week of frustration, anxiety, and annoyance is probably worth more than an email correction. I don’t expect much from companies like LinkedIn, but when their incompetence makes our lives more difficult, they could at least pretend to care a little more.

*Correction, May 25, 2016: This article originally misspelled David Sacks’ last name. It also misstated that his birthday party cost $125 million. It took place in a house then being sold for $125 million. (Return.)