Of the 1.2 billion people on Earth attempting to learn foreign languages, 800 million have chosen to study English, and they are probably not doing it to binge-watch House of Cards or read the collected works of Sir Walter Scott. Learning English has become synonymous with economic advancement across the developing world. Research from the British Council suggests that just knowing the language equates to a 25 percent bump in earnings, and many fields, from tourism to academia, have become practically impossible to enter without it. As a result, demand for English education is exploding. China has 100,000 native English instructors and is still hiring. In South Korea, which apparently spends $15 billion a year on private English education—more than 1 percent of its GDP—some parents have gone as far as surgically altering their children’s tongues to improve their pronunciation.

At some point, most nonnative speakers who want to cash in on their English—to go to university abroad or land a job with a multinational corporation—will have to take a test, probably one with a long acronym: the TOEFL, the IELTS, the TOEIC. These grueling exams can cost $200 or more, a small fortune in some developing countries, and must be taken at an official testing center, which could be hundreds or thousands of miles away. Like most high-stakes standardized tests, they have been the subject of withering criticism: that they don’t measure the kind of real-world English spoken in lecture halls or board rooms, that performance is just a proxy for socio-economic status, that cheating is widespread. What if you could make a cheaper, shorter, smarter test? Shouldn’t there be an app for that?

Right now, Carnegie Mellon University is quietly conducting a pilot study—brokered by a former dean of admissions at Yale and involving 10 other elite American institutions, a confidential mix of Ivies, state schools, and liberal arts colleges—to see whether a 20-minute exam taken via smartphone could evaluate the English ability of incoming international students better than existing tests such as the TOEFL. Originally $20, the test will be priced at $49 as of May 1. If it holds up under scrutiny, it would not only have a profound impact on the world of international admissions but also open up a hugely lucrative market for Duolingo, the Pittsburgh-based startup that developed the test and whose free, gamefied approach to language learning has already made it one of the most popular education apps in the world.

Neilson Barnard/Getty Images

Both of Duolingo’s founders, its Guatemalan-born CEO Luis von Ahn and Swiss-born CTO Severin Hacker, were required to take the TOEFL before coming to the United States to study. Hacker actually paid less to take his test in Zurich than his co-founder spent in Central America. Von Ahn had to fly to El Salvador to take his TOEFL because there were no seats left in Guatemala. “It cost me $1,000 to certify that I know English,” he told me, lumping together the test fee and travel expenses. “That’s like three months’ salary for most people in the developing world.”

Duolingo’s test is already accepted by the Harvard Extension School and the Max Planck Institutes in Germany. If major American universities begin to adopt it en masse, it could significantly disrupt the tightly controlled global industry for English certifications, which Duolingo values at $5 billion annually. “We want to be another option for people,” von Ahn says. “Once we’re another option, one of two things will happen. Either everybody is going to take our test. Or the TOEFL is going to have to come down to a reasonable price point. Even if all we’re able to do is make the TOEFL affordable, that alone would be good for the world.”

* * *

Duolingo’s Pittsburgh office reeks of startup: the catered lunches; the maze of table games; the standing desks; the whey-faced, bespectacled young folk passionately typing away. Now about 60 employees strong, the company was “spun out” of Carnegie Mellon’s computer science department in 2012. Since then, its app has sucked in 110 million people who are now studying one of 59 language courses. Twenty-three more are in the works, with increasingly colorful linguistic combos: Swedish for Arabic speakers, Guarani for Spanish, Yiddish for English.

The company, now valued at $470 million, has attracted an array of high-profile backers including Google Capital, the venture firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, and celebrity investors such as Ashton Kutcher. These investments reflect the tech community’s strong faith not only in Duolingo itself but also in its wunderkind chief executive.

Von Ahn, 37, grew up in Guatemala, a country where, according to the World Bank, almost half the population subsists on an average daily wage of $1.50. Compared with this group, his family was extraordinarily privileged. His father was a doctor who completed his residency at Stanford. His mother, also a trained physician, ran her family’s candy factory. Von Ahn attended the country’s best college prep academy, the American School of Guatemala, then Duke, then Carnegie Mellon, where he earned his doctorate and, at age 25, became a professor of computer science. Before turning 30, he would start two companies, sell both of them to Google, and be named a MacArthur “genius” fellow.

John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

There’s no question about von Ahn’s brilliance, but his company’s financial prospects are another story. Monetization, the bane of many promising startups, is a particularly dangerous stumbling block for Duolingo, which is free (both of ads and fees) and committed to a social mission. Most of its courses are built by volunteers. The company designed its first ones (Spanish, French) in-house but was quickly inundated with appeals for more exotic tongues. “Hundreds of the course requests made no business sense,” von Ahn says. “Teaching English to Chinese speakers made business sense. Teaching English to Portuguese speakers made business sense. But teaching Irish … to anybody? That doesn’t make sense.”

The solution was to open up the tool Duolingo used to construct courses, called Incubator, and allow any qualified person to pitch in. Bilinguals have since sent in 50,000 applications to contribute their time, 300 of which have been accepted. The typical course builder, or “mod,” donates hundreds of hours to the project. Some are motivated by altruism, helping their countries by offering languages that are in high demand at home (the case of English for Hungarian speakers). Others are driven by cultural pride, hoping to increase the global prestige of their small languages (the case of Irish, a language spoken by some 90,000 people that is currently being studied by 1.4 million on Duolingo). Finally, there are a few courses—Klingon comes to mind—that are the work of seriously devoted dorks.

It’s hard to imagine ever becoming fluent in a language via Duolingo alone, but the app is certainly more productive than Candy Crush or whatever other gently stimulating cognitive time-suck eats up the interstitial moments of your day. Exercises involve translating, reciting short texts, matching words to photographs, picking out correct sentences from incorrect ones. Lessons are bite-size, broken down into various levels. Points (or “lingots”) are awarded for successful completion. There’s a social aspect, allowing you to compete against friends. A little neon green owl, sometimes dressed in gym sweats, urges you to keep practicing. One study, commissioned by Duolingo and carried out by professors at Queens College and the University of South Carolina, made the eyebrow-raising claim that an average of 34 hours spent on Duolingo is equivalent to a full semester of language instruction at a university.

Duolingo’s first attempt to monetize was daring and inspired but ended in disappointment. The idea was to teach people languages and then offer them the chance to “practice” what they learned by translating short texts—supplied by clients such as BuzzFeed and CNN—from their target languages into their mother tongues. Translation by a committee of neophytes may seem like a recipe for garbled prose. But through the miracle of crowdsourcing, Duolingo’s translations were shown to be surprisingly accurate, and the company still provides Spanish translations of news articles to CNN.

Von Ahn says the problem with translation—as most translators know—is that it’s “a crappy business.” Competition from computer-assisted translation companies drives per-word rates lower and lower, and as the company scaled, it would need a larger and larger staff of quality control and sales agents to monitor workflow and find new clients. “It was a race to the bottom,” he says.

But in 2013, a new opportunity presented itself. Duolingo started getting requests to offer some kind of English certification test. The app’s users wanted a credential proving that their language skills had improved after hours studying on Duolingo, and some remote-working organizations, like Upwork, wanted a cheap, reliable way of testing the English of their prospective freelancers. It didn’t take long for the company to realize the existing market for English certifications was huge and dominated by just a few old-fashioned companies, which is to say: ripe for disruption.

The job of designing Duolingo’s test fell to Burr Settles, a former postdoctoral researcher in Carnegie Mellon’s computer science department. Settles specializes in computational linguistics and machine learning. His previous project, N.E.L.L. (Never-Ending Language Learning), involved writing software that could teach itself English by crawling the internet and absorbing hundreds of millions of documents. Settles says that was a cakewalk compared with what he’s been up to at Duolingo. Developing a good 20-minute test of English has been “the most challenging thing I ever worked on.”

* * *

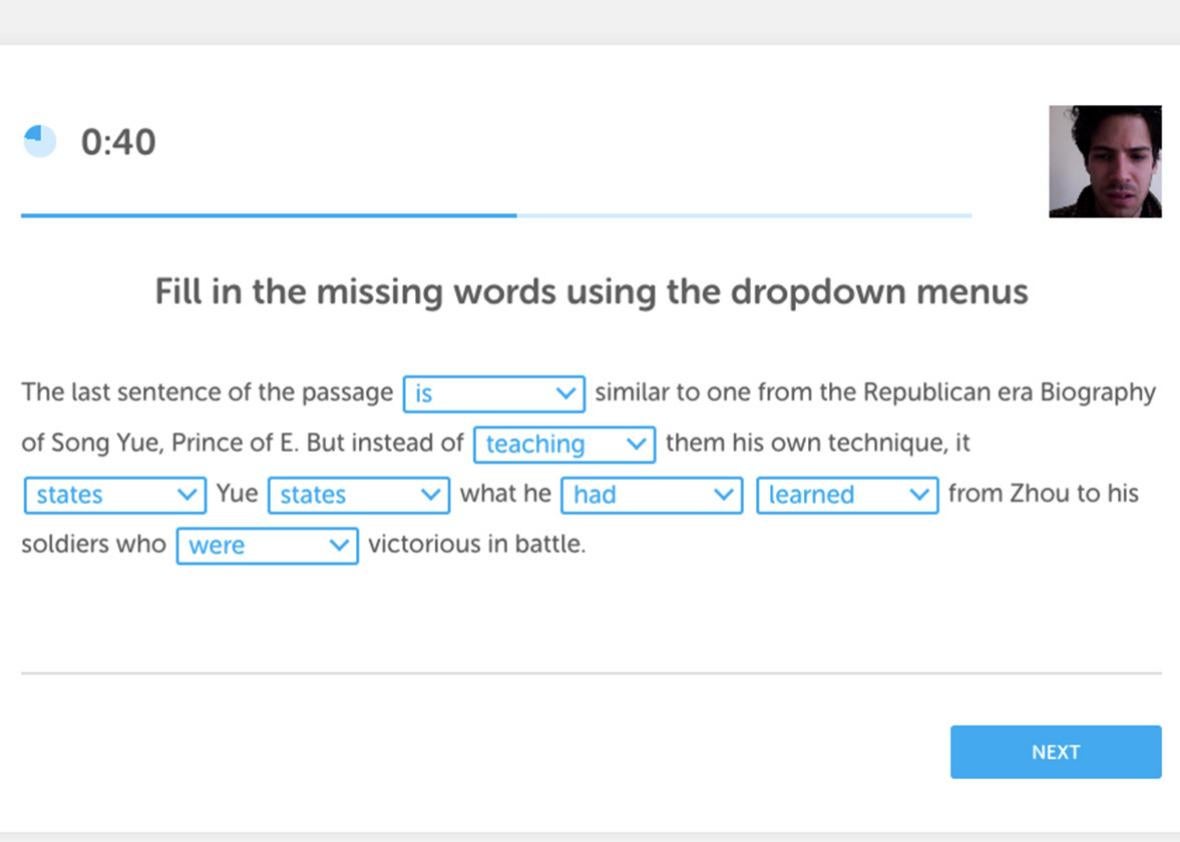

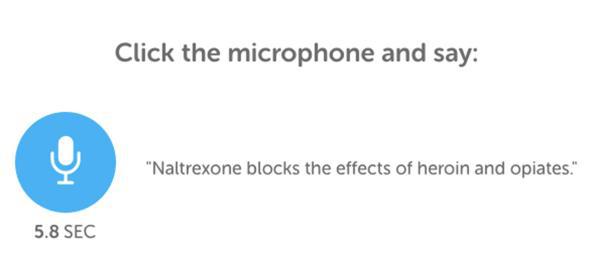

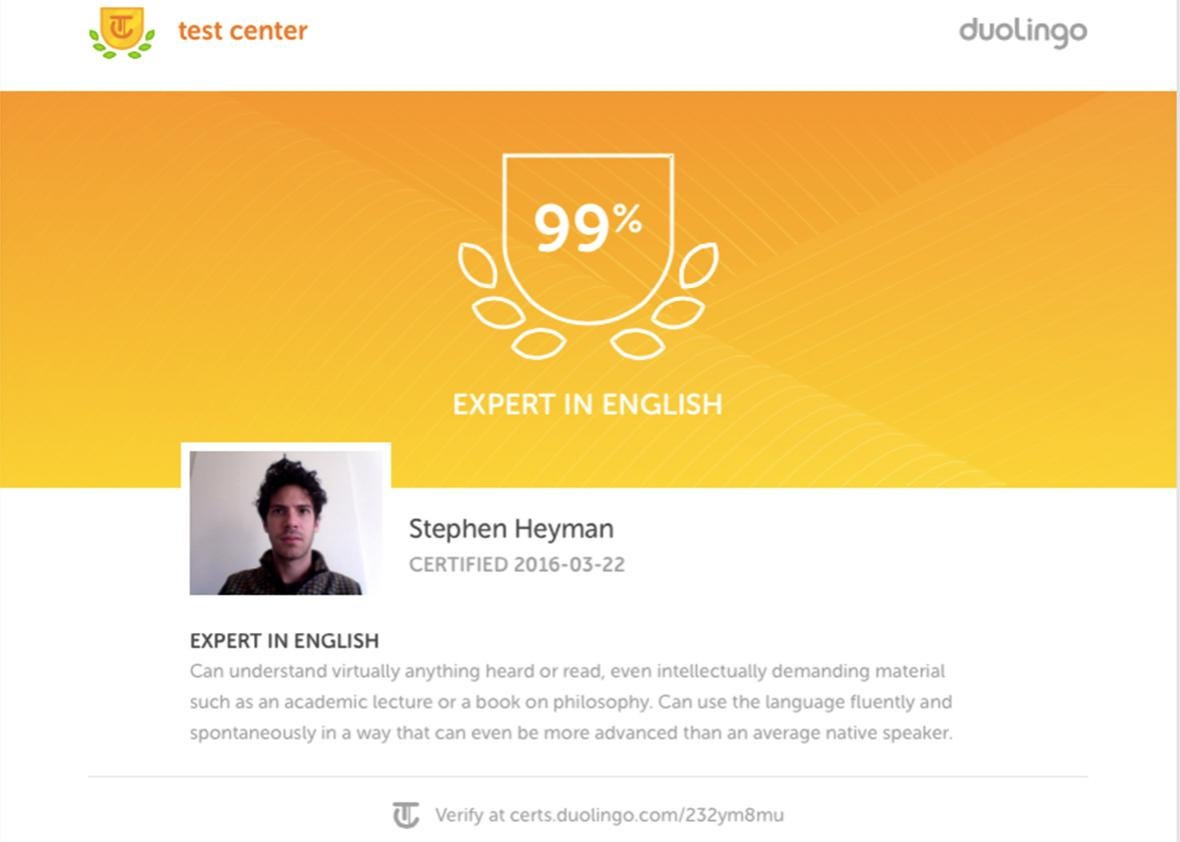

What is—depending on your perspective—incredible or suspicious about Duolingo’s test is that it claims to predict your ability to speak or write English without actually asking you to speak or write English. You don’t have to generate any original language but just go through a bunch of multiple-choice exercises and transcribe and recite short texts. From this, the exam spits out a score on a 100-point scale from beginner to expert. (A typical minimum cutoff TOEFL score for students who want to study in the U.S. is around 80, which corresponds to a 50 on the Duolingo test.)

The test is broken down into four types of exercises: vocabulary (picking out real words from a list of fake words), cloze passages (completing sentences with missing words), listening (transcribing a spoken text), and “speaking” (reciting a written prompt). Settles points to research indicating that many of these tasks are “highly predictive of overall language ability”—people who perform well on them tend to be proficient users of English. Some sentences are culled from novels, news articles, or encyclopedias in the public domain. Settles and his team spent a lot of time designing natural language–processing algorithms that could read through the giant corpus of texts available online, automatically create appropriate test items, and then calibrate their difficulty. Because the test is “computer-adaptive,” it becomes harder or easier as you give right or wrong answers, allowing your English level to be quickly pinpointed.

Dualingo

The reason Duolingo’s test is so cheap is that it is generated and scored automatically. Most of the test’s cost is spent on security, which, given the exam’s on-demand, web-based nature, required a lot of forethought. A test-taker must take a picture of herself and of her government-issued ID with her device’s camera. Autocorrect, spell-checking, and other assistive devices are disabled. Headphones are not allowed; you must use your device’s speakers and microphone.

The entire test session is video-recorded and remotely monitored by proctors from a third-party company who watch for irregularities—eye contact that doesn’t fit the right pattern, speech that doesn’t match up with the video. Because testers can’t see or communicate with the proctors, there’s no possibility of bribing them—which has happened with other high-stakes English tests.

To better understand Duolingo’s English test, I decided to take it myself.

Naturally, I went in with the swagger of a native English speaker and was so confident that I even handicapped myself beforehand by having two glasses of Jurançon Sec with lunch. While the first test questions were easy, some of the computer-generated content struck me as bizarre. For a speaking exercise, I was asked to recite the following sentence—“He missed getting his butt kicked, so he created a new hero to kick it for him”—but could not do so without laughing.

Nevertheless, I must have been breezing through most of the questions because the test quickly adapted. Suddenly, picking out real English words from fake ones seemed trickier, and I began to doubt myself. Raviolate and zaibatsu—clearly nonsense. But what about illuminary? Or sinker? Then, the test asked me to recite sentences with a few unpronounceable scientific terms: naltrexone, something called an omnidirectional supercardioid condenser.

Dualingo

After dispatching a few more tasks, I was finally presented with a short paragraph about someone named “Song Yue, Prince of E,” which contained a number of missing words, mostly verbs. I had to fill in the blanks with selections from a drop-down menu. Maybe it was because of the wine, or maybe my reading comprehension has deteriorated significantly since Mr. Greydanus’ SAT prep class, but I was stumped. Time ran out before I could answer. I began to worry that my grip on English was more tenuous than I ever imagined. But a few hours later, I received my score: 99th percentile. An accompanying certificate stated that I could “understand virtually anything.” Even though I was drunk and suffering a crisis of confidence, the algorithm was able deduce that I am native in English, much to my relief.

Dualingo

* * *

It is hard to know whether the huge testing companies that control the English certification industry view Duolingo as a threat. The biggest, Educational Testing Service, the byzantine nonprofit that runs the TOEFL (and also administers the SAT), declined to comment for this article on Duolingo’s plans. It also declined to tell me how many people took the TOEFL in recent years or how much the test contributed to ETS’s bottom line, claiming such information was proprietary. An ETS representative did, however, forward me a link to an “exam critique” of Duolingo’s English test, published last year in a journal called Language Assessment Quarterly.

The article, written by Elvis Wagner and Antony John Kunnan, is the only academic review of Duolingo’s English test to be published so far in a peer-reviewed journal, and its conclusions are rather devastating. The authors deemed the test “woefully inadequate” to be used for university admissions, claiming that it “ignore[s] decades of accumulated knowledge and research about how languages are best learned and how language proficiency can be measured.” Their criticisms were technical and detailed but centered on the test’s passive nature and its lack of exercises that actually required you to produce English.

Wagner, the first author of the critique, is an associate professor at Temple University’s education school. His research focuses on language assessment issues. He has worked on a study funded by ETS, and one of his doctoral students is now an employee at the company. Despite his history with ETS, Wagner hardly thinks the TOEFL is perfect. He agrees that its security is problematic (cheating is an “ongoing concern”) and says it could do a better job evaluating the kind of real-world English—marked by pauses and connected speech—that people actually speak.

When Wagner first learned about Duolingo’s low-cost test, he immediately recognized its disruptive potential. “I really value the idea that they’re trying to make [English testing] more accessible,” he says. But he believes the reason Duolingo’s test is so cheap—it’s generated and scored by a computer—is part of the reason why it’s so flawed. “The abilities that you can assess with a computer have nothing to do with interaction, and language is all about interacting with other speakers—that includes speaking and reading and writing as well,” he says. “That is what the last 30 years in psycho-linguistics and language acquisition are all about, and this test doesn’t look at any of that.”

Settles has written up a white paper on the design of Duolingo’s test and is currently preparing it for publication, although it may not satisfy a critic like Wagner, who admits to viewing Duolingo’s test, and the pilot study to get it approved by major universities, with suspicion. “The cynical academic in me is saying, ‘Here’s this guy from Carnegie Mellon who’s sort of the web wizard that everyone just loves.’ ” (The “web wizard” here is von Ahn.) “He’s going to get some big-name schools to accept this, and I’m afraid that everyone else is going to jump on the bandwagon and there will be a lot of negative consequences,” Wagner says. “They keep talking about how Ivy League schools are part of this study. That’s very calculated: People will say, ‘If Harvard and CMU are accepting the test, then how can we not accept it?’ ”

This, essentially, is Duolingo’s plan of attack. Von Ahn and his colleagues believe that if they can persuade a few elite schools to accept the test, others will follow suit. They’re also developing an “interview feature” that might answer some of Wagner’s criticisms about the test’s lack of interactive language. Test-takers will soon be asked five to 10 minutes of open-ended questions, and the audio or video recordings of their answers will be shared with admissions counselors, who will be able to assess for themselves the prospective students’ grasp of the language.

* * *

The limitations of the TOEFL and other existing tests of English do not come as news to Jeffrey Brenzel, who served as Yale’s dean of admissions from 2005 until 2013 and now works in the office of the university’s president. Since last year, Brenzel has also been a consultant for Duolingo, and he was instrumental in launching the pilot study, which may pave the way for the Duolingo test to be accepted at major universities.

Brenzel says that tests like the TOEFL are very good at producing reliable results on a test-retest basis—which means the same person won’t get a vastly different score if she takes the test multiple times. Existing tests are also good at carefully vetting test questions to make sure they’re not biased and that you can make specific, academic claims about what aspect of language usage they measure. These are the kinds of things that researchers like Wagner look for.

“But the thing that you most want from a standardized test is predictive validity,” Brenzel says. This means, in the case of a test of English, does a high score effectively predict whether an international student speaks well? The number of international students in the United States has grown by 85 percent over the past decade, and Brenzel says admissions counselors are seeing more students with good TOEFL scores who, somehow, have bad English: “There are more and more false positives. And there’s a big cost to both the student and the college if an undergraduate arrives somewhere in Connecticut or Oklahoma and has paid a lot of money—because in most cases there’s not a lot of financial aid for international students—and the student is just not functional in English.”

The extent to which Duolingo’s test can help prevent this is unclear, but there are some encouraging early signs. Last year, faculty members at DePauw University in Indiana conducted one-on-one English evaluations of 32 incoming international students. These students’ ratings correlated much more strongly with Duolingo test results than TOEFL scores, especially in areas such as writing and oral fluency. Von Ahn is all but convinced that the pilot study currently underway (whose results will begin to trickle in later this spring) will show that Duolingo’s test correlates with the TOEFL. A 2014 study of about 200 international students by a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, funded by Duolingo, already suggested as much. And another study conducted last year at Carnegie Mellon’s Rwanda campus showed that the test significantly correlated with the IELTS, another popular test of English as a second language.

For Duolingo, getting universities to accept the credential would generate a huge revenue stream, but it’s not the only path to profitability. The company is also tapping into a new market for businesses that want a cheap, reliable way to certify their employees’ English. Late last year, Uber began rolling out a program in certain cities in Latin America where you can request an English-speaking driver who has passed the Duolingo exam.

* * *

Even by the standards of internet evangelists, von Ahn is obsessed by questions of scale and impact. His breakout venture, ReCAPTCHA, involved harnessing the efforts of 750 million people, roughly 10 percent of the Earth’s population. These people—you’re possibly among them—were asked to decipher strings of obscure printed characters to prove they were human before buying or signing up for things online. In doing so, they unwittingly helped digitize the historical archive of the New York Times and millions of titles in the Google Books corpus.

At Duolingo, what motivates von Ahn is the idea of using the internet’s reach to address intractable social problems. Growing up rich in a poor country had a lasting impact on him, he says. He watched what happened when a few destitute kids from Guatemala City were given scholarships to attend his fancy private school. “The change that made in their lives was insane,” von Ahn says. “These people would go from literally having a house with no floors, just dirt, and they didn’t have dinner most nights because they couldn’t afford to eat, to being able to go to college, get good jobs, pull their whole families out of poverty.”

But von Ahn doesn’t spout off facile platitudes about how education leads inexorably to social equality. In places like Guatemala, he in fact believes the opposite is often true. “The costs associated with education in many countries around the world make it so that instead of it being an equalizer, education allows the rich to continue growing but stifles the poor, who can barely afford to teach their children how to read and write,” he says.

As he sees it, the only way to radically change this is to provide quality education, ideally for free, to millions of people who don’t have it. This is Duolingo’s long-term mission (even if it’s not clear to casual users brushing up on their high school French in advance of a trip to Paris). He imagines a future in which Duolingo will develop other gamefied teaching tools for a whole slew of subjects—not just languages. On the very top of the company’s wish list is a literacy app. Von Ahn estimates that, of the planet’s nearly 1 billion illiterate adults, at least 50 million of them have smartphones. “If you teach somebody English in a non-English speaking country, they can often double their earning potential,” he says. “If they’re illiterate and you teach them how to read and write, it’s like 10x.”

These are the kinds of game-changing calculations that most excite von Ahn. But as his venture-backed company grows—having recently upgraded its Pittsburgh headquarters and opened a satellite office in San Francisco—it faces a much more prosaic problem. Duolingo may want to change the world, but first it needs to learn how to turn a profit.