When I tapped Apple Music Tuesday for the first time, my iPhone screen went blank white for several seconds before anything happened. In those seconds I felt the little tingle of anticipation that comes when you open something new and exciting—which is odd, because I didn’t expect to find Apple Music exciting.

It shouldn’t be, really. Apple Music’s core features aren’t so different from those of its nearest rival, the pioneering Swedish music startup Spotify, or any number of other options in the fast-growing field of streaming apps. You can search for any song in its massive library and listen to it instantly via your mobile data connection. You can browse new releases, personalized recommendations, and radio stations.

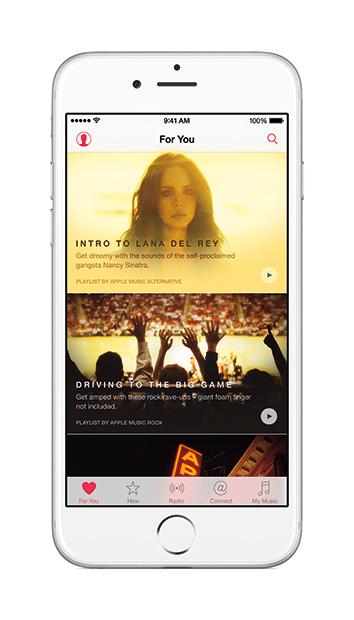

The differences with Apple Music are mostly bells and whistles—playlists handpicked by celebrities and music experts, a live Internet-radio station called Beats 1, a halfhearted artist-page section called Connect. Its personalized recommendations, clustered in a tab called For You, have a chance at being significantly better than those of Spotify, which has never quite lived up to its billing as the “Netflix of music.” But it’s too soon to say that they succeed. Oh, and Apple Music comes with an unusually generous three-month free trial. After that you’ll pay $10 a month—the same price as a Spotify subscription.

So why the excitement? Because it’s Apple. Because Apple has trained legions of loyal customers around the world to line up around the block or race to download software updates whenever it releases something new. More importantly, it has trained acolytes to open their wallets wide and trust that they’ll get value in return. And that is why it will ultimately be Apple that makes streaming the dominant form of music consumption.

Apple would like the world to think that each time it enters a new industry it revolutionizes it. That isn’t always true. The functionality of Apple products like the iPod and iPhone often bears a strong resemblance to that of predecessors like the Rio or the BlackBerry. What Apple does best is to bring the polish, approachability, and marketing savvy needed to turn a niche product into a mainstream sensation. That’s exactly what it’s trying to do with Apple Music, which wants to be the iPod to Spotify’s Rio.

Apple is later than usual to the game: Streaming music is already much more than a niche product. It accounted for $1.87 billion in U.S. sales in 2014, eclipsing CD sales for the first time. But it remained second to digital music downloads, such as those from Apple’s iTunes store. Guess who’s in a unique position to change that?

Apple still makes billions per year on iTunes downloads. But Spotify, Pandora, and other startups have eroded that business, first with their free streaming services and more recently with a paid subscription model. It’s been clear for a while now that streaming is the music industry’s future: iTunes Store sales dropped an alarming 14 percent in 2014 while revenue in the streaming sector jumped 28 percent. So Apple had a choice: Hold fast to a fading business model, or hasten the transition by getting out in front of it. It made the only sensible call.

As a latecomer, Apple would seem to face the challenge of persuading people that its $10-a-month music service is preferable to all the others out there, including Rdio, Rhapsody, Tidal, and Google Play Music. (Apple Music isn’t available yet on Android devices, but should be by fall.) But after spending just one afternoon with Apple Music, I think it has a very good chance to do just that.

The reason Apple Music will win is not because Apple Music is much better or more innovative than Spotify. It isn’t, as I’ll explain, although it’s already a viable alternative and has the potential to be more. It’s because Apple has the power to instantly reach and connect with an audience that far exceeds Spotify’s in scope and demographic diversity. Spotify’s addressable audience is young, tech-savvy music lovers; Apple’s is everyone who has an iPhone. That Apple audience is not only bigger, but more willing to pay—or, to put it another way, less willing to go out of its way to avoid paying. And on iOS devices, Apple Music enjoys a tremendous home-field advantage.

Spotify achieved the remarkable in convincing some 20 million people to sign up for its paid streaming service over the years. That’s especially impressive given the high quality of Spotify’s free service, which boasts some 75 million active users. But getting from 20 million to, say, 100 million was going to take an awful lot of advertising and marketing. I’d venture to guess that the majority of Americans still have no idea what Spotify is and have little intention of finding out.

In contrast, when Apple Music went live in the United States and 99 other countries on Tuesday, an iOS software update instantly appeared on hundreds of millions of iPhones and iPads around the world. The clean white Apple Music icon replaced the old red Music icon in the bottom right corner of countless home screens. And the moment those countless people open that app, they’ll be greeted with an invitation to a three-month free trial—after which, they’re told, they’ll be billed $9.99 a month unless they go into the settings and turn off automatic renewal. To do this requires several steps that are not at all obvious from the app’s design. For a company that so prides itself on making things so easy to use that you don’t need an instruction manual, it can’t possibly be an accident that turning off auto-renewal is harder than composing a good Snapchat Story. I’d wager most people will just accept Apple Music’s terms and forget about it.

Given all that, I wouldn’t be surprised if Apple signs up more paying customers in its first few days than Spotify does in a year. Who needs advertising when you’re already in so many pockets?

For all its advantages, Apple Music could still fail by being significantly inferior to its competitors. But on first look, it appears to be passable at worst. And it has a chance to be much better than that.

The app has five tabs: “For You,” “New,” “Radio,” “Connect,” and “My Music.” “My Music” is the equivalent of Apple’s old Music app: It contains the songs you’ve bought and paid for the old-fashioned way, whether downloaded from the iTunes store or ripped from a CD. But Apple Music and other streaming services render such music—and maybe the very concept of music ownership—functionally obsolete. After today, there is a real chance that tens of millions of Apple customers will never download a song again.

“Connect” lets you follow your favorite artists, some of whom might use the space to post exclusive content of one sort or another. I’m dubious that they’ll find it worth the trouble, unless Apple Music grows even bigger than I expect it to. “New” is, surprisingly, the tab most packed with content, not all of it new. When I scrolled to the bottom—past “new music,” “hot tracks,” “recent releases,” “top songs,” “hot albums,” and more menus than I cared to count, one of which I think had something to do with Sia—I came to one called “alternative essentials.” The contents: Nirvana’s Nevermind and Pearl Jam’s Ten. Here, the kitchen-sink approach felt un–Apple-like.

“Radio” contains not only the obligatory algorithmic, genre-based stations, but a station called Beats 1 that has actual human DJs spinning tracks that everyone listens to at the same time. It’s such an old idea that it almost feels new again: real-time, ephemeral music! In the hours after Apple Music was released, my Twitter feed lit up with people critiquing the first DJs’ song selections.

Image Courtesy Apple

The one area in which Apple might genuinely distinguish itself is the “For You” tab, with its personalized recommendations. Apple paid $3 billion for Beats Music in part to acquire its streaming service, which specialized in serving up playlists tailored to your taste. The first time you use Apple Music, it will invite you (as Beats did) to tell it some artists you like and dislike. I can’t tell you how good it felt to tell Apple Music I hate Coldplay and know that, somewhere in the bowels of its data storage, it will remember that forever.

“For You” is far from perfect: Two of the first playlists it suggested were “Intro to Outkast” and “Intro to Wilco,” which felt rather unnecessary given that I had told Apple Music only moments before that Outkast and Wilco were among my favorite artists. Better was “Indie Hits: 1999,” a playlist that was created by humans who love music rather than a machine-learning algorithm. I got Blur’s “Tender” and the Magnetic Fields’ “The Book of Love” back-to-back and was just about ready to hand over my $9.99 on the spot. On the whole, the “For You” tab feels a little thin at this point to earn Apple Music that “Netflix of music” mantle that no one has yet been able to rightfully claim. But it’s already more user-friendly than Spotify’s equivalent, the “Discover” tab.

Where Apple Music seems to fall short so far is in its customizability. Making your own playlists is the heart of the Spotify experience, and that’s a big part of why music-lovers have embraced it. Apple seems to have assumed you’d prefer to leave the hard work of playlist-making to the pros. And maybe that’s true for a lot of its target audience. If so, Spotify may continue to thrive among aficionados even as Apple Music conquers the masses.

I’ve invested enough time on Spotify over the years making playlists and customizing radio stations that I fully expect to return to it before the end of the three-month trial period. But who knows, Apple Music might win me over—or I might just forget to unsubscribe.