Despite Uber’s ubiquity these days, the sudden ascent of the car-hailing app can still feel shocking, especially when you read headlines like this one from the New York Post last week: “More Uber Cars Than Yellow Taxis on the Road in NYC.” In the four years since it became active in New York City, Uber has not only challenged the age-old taxi industry, the Post wrote, it has surpassed it. The latest figures from the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) show that there are 14,088 vehicles that use Uber’s platform in New York City, while traditional yellow cabs number just 13,587.

In New York, where all things taxi-related are at minimum somewhat controversial, the Post report was explosive. Yellow cabs are more than a staple of New York’s transportation ecosystem; they’re a symbol. It didn’t take long for the taxi industry to fire back. Late last week, the Committee for Taxi Safety, a group that represents about 20 percent of licensed yellow cabs in New York City, said it would seek a cap on the number of Uber cars allowed in the five boroughs. “It’s remarkable that this one company is able to put vehicles on the road willy-nilly without anyone saying what this means for traffic conditions or parking or the environment,” Tweeps Phillips, the committee’s executive director, told USA Today. “It’s like the city fell asleep.”

But did it? While the rise of Uber and other ride-hailing services is a significant development for urban transportation, Uber’s 14,088 cars alone might not be the harbinger of taxi obsolescence that they seem to be. Look at the data more closely, and a lot less has changed than the Post and the cab industry would have us believe.

Here’s some more context for those Uber numbers: First, while Uber’s cars might top taxis in number, in terms of total time spent on the road, the yellows are easily winning. According to the TLC, yellow cabs make an estimated 175 million trips each year, or about 485,000 per day; the average driver works 9.5-hour days. Uber, by contrast, averaged slightly more than 34,000 trips daily in New York City last fall—less than a tenth of the taxi industry’s ride volume. And the vast majority of Uber’s New York drivers either work one to 15 hours a week (42 percent of the total) or 16 to 34 hours (35 percent)—well below the hours logged by cabbies.

“Yellow-cab rides significantly outstrip the number of black-car rides, including those dispatched by Uber, so the number of their affiliated vehicles in and of itself doesn’t nearly paint a complete picture,” says TLC Chair Meera Joshi.

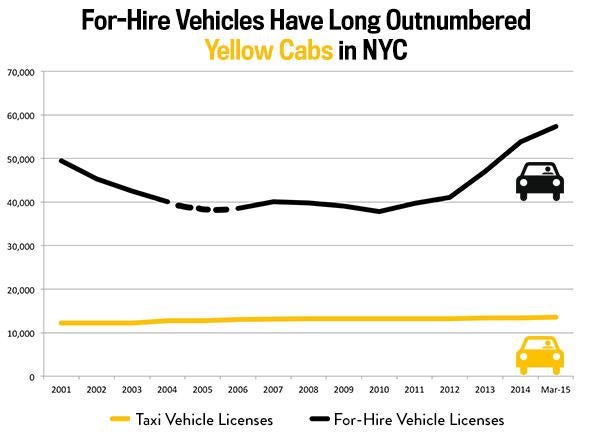

What’s more, so-called for-hire vehicles—black cars, limousine services, and now Uber—have historically outnumbered taxis in New York City. And it’s likely that many of the cars currently registered with Uber were previously driving for other black-car services in New York. Here’s a chart I pulled together showing the annual totals of for-hire vehicle (FHV) and taxi licenses in New York City between 2001 and now. (The TLC data doesn’t give a figure for for-hire vehicles for 2005, so I smoothed the curve.) The ranks of FHVs have certainly grown since Uber entered the city in May 2011, but they haven’t exploded. In 2013 and 2014, FHV licenses increased by about 14 percent year-over-year; in the years immediately preceding that, growth was closer to 3 percent.

Data from the New York Taxi & Limousine Commission. No data available for 2005. Chart by Alison Griswold.

The sizeable gap between the cohorts of taxis and other ride providers shouldn’t be surprising. New York City has imposed a strict cap on the number of taxi medallions it gives out since 1937. Regulation was designed to stave off an industry-wide race to the bottom; in the wake of the Great Depression, demand for taxis fell as New Yorkers sought cheaper forms of transit, and many cab companies were forced to slash fares to unsustainable levels or go out of business. The goal of setting a limit on medallions was to reign in supply, thus bringing it back in line with demand.

Of course, the problem is that in the decades since, the supply of taxis has barely edged up, while the demand for them has skyrocketed. When the limit first went into effect in 1937, taxi medallions sold for $10. By 1950, the going price had risen to $5,000; in 2013, it peaked at a stunning $1.05 million. Since Uber and its peers began operating in New York City the price of a medallion has fallen—in January, they were trading at $805,000, about 25 percent off their all-time high—but is still enough to buy a decent apartment in Brooklyn.

The taxi industry is taking issue with Uber’s ballooning numbers for two reasons. First, Uber’s technology gives the company a serious advantage over yellow cabs; e-hails allow drivers to waste less time finding passengers, and surge pricing lets fares soar over cabs’ metered rates. Second, the taxi industry claims that the proliferation of Uber cars is worsening gridlock and pollution by putting more cars on the road.

For both these points, Uber has ready responses. “We are extending the reach of mass transit, eliminating transportation deserts, focusing our service in the outer boroughs where taxis don’t go, and investing in taking 1 million cars off of New York City roads with UberPOOL,” says Matthew Wing, an Uber spokesman. Internal Uber data shows that 26.3 percent of the company’s pick-ups are made in boroughs outside Manhattan, as compared to 6.3 percent of pick-ups for yellow cabs.

Uber also points out that the taxi industry’s support of green initiatives is spotty at best. In 2007, then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed a rule that would cut emissions by replacing most taxi vehicles with hybrids by 2012; in 2008, a federal judge blocked the initiative after taxi owners sued. The taxi industry has also opposed the creation of more green cabs, which service outer boroughs and noncentral parts of Manhattan, while advocating for more yellow cab medallions.

It’s unclear what impact ride-hailing services like Uber are having on the environment and congestion. A working paper released by researchers at the University of California Transportation Center in August 2014 found that, in San Francisco, “ridesourcing enables lower levels of driving among vehicle owners,” but so far “seems to have had little impact on auto ownership.” For everyday commuting, the authors added, ride-hailing services seemed to complement rather than substitute public transit. Uber might be increasing gridlock, but it also might not be. Right now, no one really knows.

But the biggest point that’s been largely overlooked in this latest numbers debate is whether in growing its own ranks, Uber is adding cars to the road or merely absorbing the licenses of existing drivers who’ve switched their corporate allegiances. During Uber’s first few years in New York, lots of new drivers joined up, but plenty of longtime drivers also transferred their base affiliations to Uber’s platform from other black-car companies, lured by promises of higher wages and more flexible hours. (Although as I reported last year, Uber isn’t able to substantiate its most enticing promise—that its median New York driver earns close to six figures.)

When I asked the TLC if it could tally how many of Uber’s drivers are new, as opposed to transfers from other services, a spokesman said the manner in which the data is collected makes that prohibitively difficult, if not impossible, to calculate. Uber also wasn’t able to come up with a figure, but Wing told me the assumption about how many cars Uber has put on city streets “is inflated because it doesn’t account for the many driver-partners who switched over to Uber from other existing bases in the city.”

So are there a lot of Uber cars in New York? Yes. Will their numbers keep growing? Probably. Is this bad for the city’s traffic patterns and environment? It’s hard to say. But does the revelation that there are “more Uber cars than yellow taxis on the road” mean we need to be shocked and scared and cap their growth? Almost definitely not. In New York City’s modern history, black cars and other for-hire vehicles have always outnumbered taxis. The difference is that with Uber, that’s begun to seem like a serious threat.